Keywords:

Fab Lab, grass roots innovation, 10k Fab Lab, maker movement, political economy

Peter Troxler

When Neil Gershenfeld started the Center of Bits and Atoms (CBA) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2001 to explore the merging of physical and computer science, part of his proposal was an outreach programme. It should bring the CBA’s technology to classrooms and to the developing world. Outreach Fab Labs were built in Boston, in Costa Rica, in the village of Vigyan Ashram (India), and in Ghana. The MIT Fab Lab in Northern Norway, the oldest Fab Lab in Europe, was allegedly conceived in 2002, started in 2003 and formally opened in 2005. The aim, however, was to keep the number of Fab Labs at a level that would be easy to oversee and manage. The MIT’s “Physical Map of the World, April 2004” showed ten Fab Labs in the Americas, nine in Africa, eight in Europe and five in Asia, a total of 32 FabLabs. No one would have thought then that ten years later a single, small country like the Netherlands would boast as many Fab Labs as there were globally in 2004, and that the number of labs world wide would have grown tenfold.

Fab Labs were conceived as an outreach programme to the Center of Bits and Atoms research programme at MIT. From a handful of initial labs they grew to tens in the first five years of the programme, and to hundreds in the decade thereafter. This article pinpoints one event that crucially contributed to that growth and identifies the challenges the global network of Fab Labs faces today. It concludes with a critical, but positive, outlook on the future of the Fab Lab community and the challenges it faces.

From a Book to National Strategic Programmes

2005 saw the publication of Neil Gershenfeld’s book ‘FAB: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop – from Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication’, and with it growing public awareness of the phenomenon. The same year, South Africa was the first country to implement a national Fab Lab programme through the Advanced Manufacturing Technology Strategy of the country’s national Department of Science and Technology (Borde & Coetzee, 2005). This included setting up six labs within the time span of two years. The CBA was on a route of “establishing a growing network of field Fab Labs to explore the prospective users and applications of these technologies” (Mawson 2005).

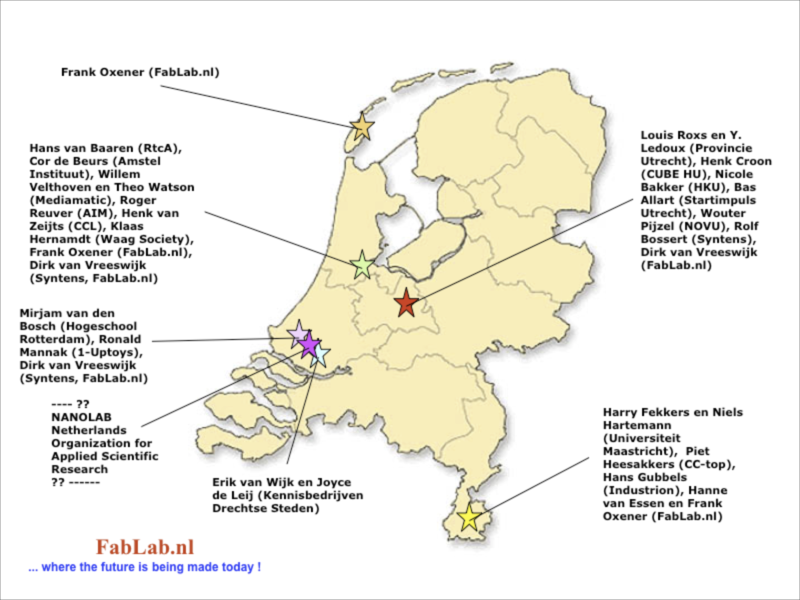

In 2006, a Dutch website for Fab Labs was set up with the aim to promote FabLabs in the Netherlands; a year later, a private Fab Lab foundation was set up in the Netherlands. Two media institutes in Amsterdam, Mediamatic and Waag Society, started their respective Fab Labs in 2007, as temporary experiments. Something different was going on: this was not a centralized, state-run programme but loose groups of individuals and private organisations that were keen to have their Fab Labs, a group of enthusiasts, loosely organized in the Dutch Fab Lab foundation, gathering around the idea of Fab Labs and the slogan “Where the future is being made today!”

When Neil Gershenfeld was invited to speak at the PicNic festival in Amsterdam in 2007 he took the opportunity to offer the CBA’s collaboration with the Dutch Fab Lab Foundation. Reportedly that collaboration would have entailed paying the CBA a development fee of some hundred thousand Euros – not as absurd a figure if one takes into account that the CBA’s initial 13.75 million dollar NSF grant was about to run out in 2008. Unlike everywhere else, however, foundations in the Netherlands are not as a rule established through some generous endowment but rather the most lightweight instrument to legally incorporate a not-for-profit organization; so many foundations in the Netherlands have very little or no capital at all. The Dutch Fab Lab Foundation being no exception they had to politely but decidedly decline the collaboration offer from CBA – and probably feared that herewith their dream of bringing Fab Labs to the Netherlands had found a premature end.

Business Model Innovation

But the unexpected happened. Neil Gershenfeld was rather supportive of the idea and encouraged the Dutch to push ahead. “It is going fast in your country; that doesn’t surprise me. The Dutch are good at collaborating and working in networks. That is crucial. You can spearhead this innovation” (Dalm 2007, own translation). The coming years, the Netherlands saw a rapid and sustained growth of the number of labs. The two Amsterdam labs were merged into the one that became a fixed asset of Waag Society’s portfolio. In 2008, three more labs started. Protospace in Utrecht got money from the European Union’s regional funds. Cab Fab Lab in The Hague started at the local incubator “Caballero Fabriek”. Fab Lab Groningen found local subsidies to pay its first years.

The next Fab Lab to join the rapidly growing Fab Lab community in the Netherlands was Fab Lab Amersfoort. This one was radically different from the other labs in the Netherlands and even in the global network. It was not part of a university or high school nor of any other established institution. It was not funded by a government or industry grant. This was a lab that had been set up by a collective of artists “in 7 days with 4 people and about EUR 5000” – or at least that’s the narrative of their “Fab Lab Instructable” (Zijp 2011).

Fab Lab Amersfoort was different to with regard to the CBA specifications and previous practice in a couple of respects. First, it was truly independent. Second, it differed in size and equipment from the initial model which required an investment of roughly 100k US Dollars (or Euro) – interestingly, for some reason, the press keeps citing a figure of around 30k for initial investment, not taking into account expenses for hand tools, computers, networking and consumables. Amersfoort showed that many capabilities of a Fab Lab could be achieved with a 5k Euro investment.

The Dutch developed three elements that had not been part of the outreach strategy of CBA: labs without a formalised relation with MIT, a reinterpretation of the basic machine set to match smaller budgets, and the can-do attitude of an independent, grass roots approach. They could most aptly be described as a fork of the model devised by CBA, as innovations on the initial outreach and business model. The Fab Foundation that spun out of CBA officially declares that a CBA partnership for setting up labs “isn’t realistic for a community lab. It’s more appropriate for research agreements, or for large networks of labs, say for a country like India” (Fab Foundation 2013). The principle of “powers of ten”, Fab Labs at the size of 10k, 100k and 1000k USD investment, officially became an element of the programme in 2013, when Neil Gershenfeld tasked a working group at the annual gathering in Yokohama to establish an official inventory for a 10k Fab Lab; this was presented at a Fab Lab meeting in Moscow (Bakker 2013). The idea of grass roots Fab Labs has spread globally and is practiced next to the “conventional” mode of a host agency that takes ownership of the Fab Lab. The Fab Foundation acknowledges that “[t]he cheapest and fastest method to get a fab lab is to buy and assemble it yourself” (Fab Foundation 2013). The CBA scrutinized those innovations, accepted them and eventually integrated them into their outreach narrative.

Growth and Challenges

Indeed, the Netherlands counts forty-one labs, of which seven under development, the Netherlands maintains the highest density of Fab Labs in Europe and world wide [1] with ten times as many labs per inhabitants than the Unites States of America, where the concept was created, and twice the density of France or Italy. The development of Fab Labs in Europe appears to have generated a higher density in countries where the grass roots approach has taken root – Switzerland, Italy and France. While an important proportion of the Fab Labs in Spain, the UK and Germany are grass roots initiatives, their population is dominated by “conventional” labs at host institutions.

Table 1: Density of Fab Labs per inhabitants for countries with more than 10 Fab Labs (as of June 2014).

| Country | Fab Labs* | Population [millions] |

Density*** |

| Netherlands | 34 (12) | 16.9 | 0.5 |

| Switzerland | 11 (8) | 8.0 | 0.7 |

| Italy | 48 (>50 %**) | 60.8 | 1.3 |

| France | 51 (>50 %**) | 66.6 | 1.3 |

| Spain | 15 (6) | 46.7 | 3.1 |

| Canada | 10 | 35.4 | 3.5 |

| UK | 17 (2) | 64.1 | 3.8 |

| Germany | 19 (9) | 80.7 | 4.2 |

| USA | 58 | 318.8 | 5.5 |

| Japan | 12 | 126.7 | 10.6 |

| Brazil | 11 | 202.7 | 18.4 |

Source: fablabs.io and own investigations, non European countries in italics, population figures according to wikipedia.org

* in brackets: number of grassroots Fab Labs where available

** estimates

*** million inhabitants per Fab Lab

The rift between hosted Fab Labs and grass roots Fab Labs poses an important challenge for the global Fab Lab community, particularly when important voices – such as the Fab Foundation – spend one sentence on the “do it yourself” approach and nine paragraphs on describing the hosted approach. The smallest problem is that it attracts management consultants who try to flog their outworn recipes from conventional business development to anybody planning to set up a Fab Lab – which must appear utterly counterintuitive if one assumes that Fab Labs are indeed a new manufacturing paradigm, as Neil Gershenfeld claims (2005), or the notion that they are still “closer to the laboratory ‘world on probation’ than to the sphere of production” (Dickel et al., this issue). A bigger worry is that the community could split into different classes of Fab Labs with their own practices and institutions – more centrally, hierarchical in the case of the hosted Fab Labs, more decentralized or poly-centric and peer oriented in the case of the grass roots labs. Such a stratified community could over time lead to the different classes failing to reconnect, which could result in labs closer to central power getting more attention, becoming more central to the narrative of Fab Labs, and receiving a larger share of business through the network than the decentralized ones. Conversely, the community could loose out on connecting to its fringes, fail to embrace and develop diversity, and miss important input that in the past lead to substantial renewal and enlargement of the network.

Another challenge emerges when considerable amounts of money are involved. In 2013 the French government was in talks with TechShop to convert some of the existing “espaces publics numériques” (public digital spaces) into digital fabrication spaces. Accidentally, members of the emerging Fab Lab community in France got involved with the government on this subject and convinced the ministers to establish a grant to support Fab Labs instead. The call received 154 submissions of which 14 were retained. For the emerging grass roots community, however, there were too many “unknown” players among the winners, only three were known Fab Labs among which the one initially involved with the government. Rumour had it that some received substantially more funding than the maximum of 200k that was initially announced. The French Fab Lab community was thrown in confusion. Part of it was due to bad communication on behalf of the French government and a selection process that was considered obscure. And part of it was due to the unclear role members of the community played in this issue. Sources of money are an issue as well. In 2012 Make Magazine came in for a lot of flak from hackers when it accepted DARPA sponsoring for its educational “Mentor” programme. When the Fab Foundation in 2013 announced sponsorship of ten million dollars from Chevron news was received with cheers – and some raised eyebrows. The first Chevron Fab Lab is to be opened in Bakersfield, the oil capital of California – and close to the Monterrey shale gas reservoirs. On the other hand, the Fab Labs in Derry and Belfast in Northern Ireland are funded with 1.3 million Pounds from the European Union Peace Programme. Big money does not necessarily imply bad intentions, but it might attract accusations of corporate “Fab-washing”. The network has to develop a critical and constructive way of discussing how to interact with corporations, the government or the military – both as a community and at the individual labs.

Other challenges in the Fab Lab community are its position with regard to other players in the Maker Movement, particularly Makermedia – spun out of O’Reilly publishers and owner of brands such as Maker Faire, Make Magazine, etc. – and Techshop. The image of the maker as a creative individual who in his perseverance echoes the Randian hero which is mainly promoted by these two entities does not exactly match up with the ideals of peer-production (see Kohtala & Bosqué, this issue). The predominantly male clientele of the Maker Movement – to which the introduction of figurehead women such as Lady Ada is no redress – calls for feminist critique (see Toupin, this issue). The mainly technology-driven pursuit of Fab Labs merits critical scrutiny, especially when it comes to bringing Fab Labs to developing countries (see Chan, this issue). Finally, many Fab Labs – hosted or grass roots – depend on subsidies for their survival and struggle to balance leisurely activities and determination to create commercially useful results, so they are well advised to take Smith’s suggestion (this issue) to “address [their] relationships with political economies.”

In principle, I feel that Fab Labs, through their historical development and thanks to the open minds of their founders, are well positioned to face those challenges and develop adequate responses. In practice, however, I foresee this development as rather difficult. Calling for central solutions is easy, big money is captivating, and it is tempting to just accept the images of heroes (male or female), of technology as neutral, and the promise of easily obtainable subsidies. Fab Labs, in their diversity of manifestations and their academic and grass roots foundations, however, are best positioned in the maker movement to have these discussions and come up with valid answers.

Endnotes

[1] With the exception of small countries with less than a few Mio inhabitants (such as Luxembourg, Curaçao and Suriname) which due to their minimal population distort any such comparison.

References

Bakker, B. 2013. On Small Fab Labs. [Blog post] Online at: http://fablab.nl/2013/11/06/10k-fab-labs/ [Accessed 20 June 2014].

Dalm, R. v. 2007 Iedereen Leonardo da Vinci. Kennisintensief werken gaat een volgende fase in met ‘persoonlijke digitale fabricage’. Het Financieele Dagblad, 05.11.2007, Carrière, p. 12.

Fab Foundation 2013. Setting up a Fab Lab. Online at: http://www.fabfoundation.org/fab-labs/setting-up-a-fab-lab/ [Accessed 20 June 2014].

Gershenfeld, N. 2005. FAB: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop. From Personal Computers to Personal Manufacturing. New York: Basic Books.

Mawson, N. 2005. MIT-associated lab launched in SA. Creamer Media’s Engineering News. Online at: http://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/mitassociated-lab-launched-in-sa-2005-06-29 [Accessed 20 June 2014].

Oxener, F. 2007. Dutch Fab Lab Foundation. Presentation at Fab 4. The Fourth International Fab Lab Forum and Symposium on Digital Fabrication, Chicago, 19-24 August 2007. Online at: http://cba.mit.edu/events/07.08.fab/Netherlands.pdf [Accessed 20 June 2014]

Zijp, H. 2011. The grass roots FabLab instructable or How to set up a Fab Lab in 7 days with 4 people and about EUR 5000. Online at: http://www.fablabamersfoort.nl/downloads/fablab-instructable.pdf [Accessed 20 June 2014].