by Rachel Simone Weil

“The Nostalgia Question” and Feminist 8-bit Game Hacking

Decades after their first appearance, the distinctive, low-resolution sights and sounds of early video games continue to captivate and delight. Pixelated visual art and bleepy chipmusic reminiscent of 1980s video games have come to constitute their own style and art form, making appearances in film, illustration, pop music, fine art, fashion, and consumer goods. (It remains to be seen whether the recently released and widely derided Pixels, a big-budget Adam Sandler film ostensibly about killer 1980s video game characters, is evidence that this art form is on its way out.)

Many have written about the contemporary popularity of the 8-bit aesthetic, and those who do frequently turn to the nostalgia question. Do happy childhood memories of playing old video game consoles fuel our appetite for pixel art and the sounds of the twentieth-century video arcade? Or must 8-bit stand apart from this framing, and from nostalgia, in order to be taken seriously as an art form?

From 2011 to 2014, the American public broadcast channel PBS published an online video series called Off Book. Off Book sought to cover “cutting edge arts,” and topics related to video games made numerous appearances throughout the series (PBS Video, n.d.). In a 2012 episode titled “The Evolution of 8-bit Art,” academics, musicians, and artists describe the personal and broader cultural value of the 8-bit aesthetic. Some interviewees featured in the short argue that nostalgia plays a role in the genre’s appeal, while others disagree, citing alternative aspects such as simplicity and creative constraints. But the overall narrative of “The Evolution of 8-bit Art” suggests that framing 8-bit as purely nostalgic is somehow cheap, for real art must exhibit something deeper, some kind of transformation or subversion. As PBS describes it:

The idea of 8-bit now stands for a refreshing level of simplicity and minimalism, is capable of sonic and visual beauty, and points to the layer of technology that suffuses our modern lives. No longer just nostalgia art, contemporary 8-bit artists and chiptunes musicians have elevated the form to new levels of creativity and cultural reflection (PBS, 2012).

“The Evolution of 8-bit Art” is representative of a prevailing way of talking about 8-bit arts as moving past nostalgia and toward something more meaningful. A similar take can be seen in an article about chipmusic from online art and technology site The Verge, appropriately titled “Blip Festival 2012: Chiptunes Move Past Nostalgia and into the Future” (Robertson, 2012). What analyses like these seem to suggest is that framing the 8-bit aesthetic as merely nostalgic for old video games is cheap or uninspired, while removing as much video game context as possible is positioned as more transformative and artistic.

I would argue that, in fact, an engagement with nostalgia and the history of games culture can be deeply transformative—the two are not mutually exclusive. Likewise, 8-bit works that strip or reject gaming contexts and nostalgia are not necessarily transformative, either. Suggesting that the commercial history of the Game Boy handheld game console doesn’t matter in the context of chiptune, or that 8-bit illustration is simply an exercise in minimalism, for example, is ahistorical and apolitical, closing off paths of deeper arts inquiry.

In her 2006 book Retro: The Culture of Revival, art historian Elizabeth Guffey examines our cultural relationship with retro revivalism, which “views the past with trendy detachment” (Guffey, 2006, p. 162) and can discard complex politics. Guffey continues:

At best, retro recall revisits the past with acute ironic awareness; self-conscious in its recollection, retro revivalism lays bare the arbitrariness of historical memory. At its worst, retro pillages history with little regard for moral imperatives or nuanced implications. As entire periods of the recent past are introduced into the popular historical consciousness through retro’s accelerated chronological blur, we risk incorporating its values as well. (Guffey, 2006, p. 163)

I believe that when the distinctive look of 8-bit game console graphics or the distinctive sounds of a Game Boy are stripped of their relationship to 1980s and 1990s video game history in the name of “trendy detachment,” we risk incorporating unexamined values while losing opportunities to craft meaning from triumphs and failures of the past.

In my own practice as an 8-bit game hacker, programmer, and artist working in the chipmusic scene, I work to uncover latent values and assumptions built into the 8-bit aesthetic and video game nostalgia. Specifically, I engage with the ways in which the NES video game console intersects with 1980s and 1990s girlhood. How might women uniquely interpret and reinterpret 8-bit visual language from an era in which gaming was primarily conceived of as a boys’ pastime, in which very few games were marketed to girls, and in which girls were often discouraged from being present? Can women feel nostalgic about games they were not permitted to play as children? What does it mean to depoliticize or repoliticize a device called “Game Boy?” For me, focusing centrally on nostalgia and gaming has not been a cheap gimmick or artistically vacuous, but rather a vitally necessary form of critique, rebellion, and reconciliation.

I didn’t grow up playing the 1980s NES game console, but I recall watching my cousins play; Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt were in frequent rotation. I discovered (or rediscovered?) 8-bit aesthetic years later, as a teenager, browsing internet forums and pixel art trading websites in the early 2000s. I learned about growing hobbies like “retrogaming” (playing and collecting old games), “pixeling” (creating computer art pixel by pixel), making chipmusic, and hacking old games through the use of game emulators, hex editors, and other specially-designed software. While the aesthetic was somewhat familiar to me, it felt entirely new. Iconic video game characters could be modified, improved, and blown up to inordinate sizes on screen, allowing a detailed study of each pixel placed. Game sprites could be redrawn, recolored, and placed back into their native games. And so we got Mario with a cowboy hat, Fat Mario, Astronaut Mario, Nude Mario.

Pixeling, making chipmusic, and hacking NES games captured my imagination by bringing together my interests in computing and crafting. (It is worth noting that the early 2000s also saw the rise of craft activism, or “craftivism,” and the popular feminist reclamation of crafts such as knitting and cross-stitch, both forms of pixel art in many respects. The relationship between these concurrent movements is of particular personal interest yet relatively unstudied at the present time.)

As a teenager, I understood NES game hacking as somehow related to the idea of “childhood memories” despite not personally having had much access to these games in my own childhood. Thus, when I began making my own NES game modifications and later, my own demos and games programmed in 6502 assembly language, I pushed the work through the filter of my own childhood nostalgia. The games and artworks I created were—like the playthings of my youth—sugary-sweet and ultrafeminine.

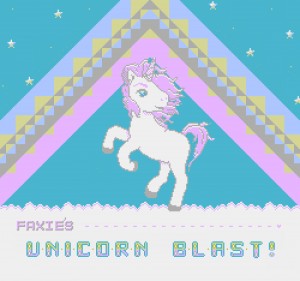

Hello Kitty Land, a game hack that I began working on in 2002, was my earliest approach to this idea. The hack transforms the revered game Super Mario Bros. into a pastel-hued version featuring Sanrio characters such as Hello Kitty. Faxie’s Unicorn Blast (2010) is one of the earlier game demos that I programmed from scratch; it reimagines the side-scrolling space shooter by replacing the typical warship with a cute toy unicorn. Its title screen draws clear parallels to the 1980s My Little Pony cartoon and toy line, simultaneously nodding to my own childhood memories and to the preponderance of NES games based on boys’ media and toy franchises (G.I. Joe, Monster in My Pocket, and Micro Machines, among others). With the exception of the 1991 NES game Barbie, girls’ toy franchises saw little representation on the boy-oriented NES; Faxie’s Unicorn Blast whimsically suggests a shift in that imbalance.

From a process perspective, this work fell very much in line with what was happening in the chipmusic scene at the same time, wherein artists were using Game Boys and other old game hardware to make new kinds of music. So I began taking my hacks, demos, and games to chipmusic shows, where they were projected behind musicians during live performances. Showing these works through large-scale projection and in combination with chipmusic posed new kinds of questions. After all, here we were, all gathered together to make something new out of old game consoles, dancing, sweaty, the nostalgia question lingering in the air, and alongside the gritty, crunchy sounds of Game Boys and Commodore 64s and other old game consoles were these most unusual pixelated flowers, lace, and candy hearts, as large and bright as they were saccharine. Despite their similar modes of production, the incongruity of the two works was obvious.

As I continued working in the chipmusic scene, considering viewers’ responses, and revisiting ideas again and again, I realized that my work was beginning to take the shape of a commentary on femininity, retrogame culture, and nostalgia. Those 8-bit flowers, lace, and candy hearts situated in old hardware felt at once sentimental, dissonant, strange, political, feminist, recuperative. After all, these things don’t belong on an NES, right? If we consider gaming in the 8-bit era to be squarely situated within boyhood, then it seemed that chiptune’s nostalgia question lacked an important statement of exactly whose past we were talking about.

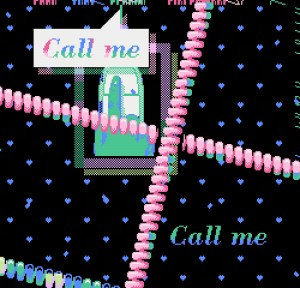

And so in the following years, my work became more overtly informed by reimagining a more feminine back-catalog for the NES. In 2013, I created Electronic Sweet-N-Fun Fortune Teller, a love horoscope game that suggests what a “girls’ romance game” might have looked like had such a thing ever been released on the NES. Providing horoscopes and love compatibility scores, Sweet-N-Fun draws from references such as teen girls’ astrology magazines and electronic diaries. Another NES piece, Look at Me Now, I’m Burning Up the Steel (2014), mashes up imagery of 1990s computing and internet connectivity with 1990s girls’ board games. Though girls’ board games are not typically associated with networking technology, the two are united in Look at Me Now through the commonality of the coiled telephone cord as a symbol in both. Hearts and a recurring bright pink telephone cord work to “girlify” illustrations of obsolete 1990s technology and the NES console itself.

Can works like Faxie’s Unicorn Blast, Electronic Sweet-N-Fun Fortune Teller, and Look at Me Now, I’m Burning Up the Steel be called nostalgic? Can we feel nostalgia for video games that never existed? In her oft-cited essay “Nostalgia and Its Discontents,” Svetlana Boym answers this question, noting that for those “who came from traditions that were considered marginal […] creative rethinking of nostalgia was not merely an artistic device but a strategy for survival, a way of making sense of the impossibility of homecoming” (Boym, 2007, p. 9). This statement resonated with me, as indeed, femininity does have a history of being marginalized within game cultures; those 8-bit flowers, lace, and candy hearts came to illuminate the impossibility of homecoming through reliving a past that never was.

The recreation of commercially-driven, stereotypical femininity might appear at odds with the many feminist approaches that seek to dismantle stereotypes about women. After all, why not disrupt the whole system of how consumer goods teach girls to be? Why not tear down the whole thing down? The approach I have put forward is just one, and certainly the sociopolitical climate should be questioned. But I would argue that valuing femininity and women’s nostalgia for girly things is a valid—and terribly underutilized—feminist practice. I see many people connect with my work because it is fun, and fun can be a powerful force to help pose serious questions. It is my hope that works like mine can point to the many ways of revaluing of women’s experiences while demonstrating the need to understand video game nostalgia not as a universal, warm and fuzzy feeling (as most popular and academic texts do) but as a broad and complex set of mechanisms for recreating, recuperating, and reimagining the past.

For me, centering nostalgia in my work as an 8-bit artist has not felt “cheap”; rather, it has opened up rich modes of feminist inquiry. Framing the NES not as some Cyberpunk Nu-Art Machine but as a 1980s 8-bit game console, situated in a certain social climate and context, has been vital, too. It is my hope that we can reconsider the refrain that 8-bit aesthetic must shed its relationship to nostalgia in order to be “real art,” or that the only way to legitimize 8-bit is through separating it from its context as much as possible. Memories of sun-drenched summers spent in front of game consoles, I argue, can coexist with artistic value, even if those summers never came to pass.

CITED WORK

Boym, S. (2007). Nostalgia and Its Discontents. The Hedgehog Review, 9(2), pp. 7-18.

Guffey, E. (2006). Retro: the culture of revival. London: Reaktion.

PBS, (2012). The Evolution of 8-bit Art.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xYL1DsY8GMI [Accessed 30 Jul. 2015].

PBS Video, (n.d.). Off Book. [online] Available at: http://video.pbs.org/program/off-book/ [Accessed 30 Jul. 2015].

Robertson, A. (2012). Blip Festival 2012: chiptunes move past nostalgia and into the future. [online] The Verge. Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2012/6/5/3063110/blip-festival-2012 [Accessed 30 Jul. 2015].

IMAGES:

*Hello Kitty Land, 2002-2015. NES ROM (hack).

*Faxie’s Unicorn Blast, 2010. NES ROM (demo).

*Electronic Sweet-N-Fun Fortune Teller, 2013. NES ROM (game).

*Look at Me Now, I’m Burning Up the Steel, 2014. NES ROM (interactive artwork).

*All images are copyrighted by the author, who grants permission for the images to be published in this issue. Please retain order of images as listed below to ensure chronology.