Keywords:

Community Networks; CNs; Commoning; WiFi; spectrum regulation

Nicola J. Bidwell

Abstract

This article considers tensions between the meanings in discourses that promote Community Networks (CNs), or locally owned, managed and operated telecommunications networks, and meanings in rural communities in the Global South that the CNs intend to serve. My analysis reflects observing international advocacy for CNs, multiple case research in Argentina, Mexico, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Uganda, and my participation in the African CN movement including setting up a Namibian CN. I propose advocacy for CNs tends to puts “commoning”, or practices that produce, reproduce and use the commons, at the periphery. My analysis shows that advocates for CNs tend to reify relations and bound resources in CNs and omit the way that the fabric of a CN is embedded in the ongoing trajectories of inhabitants’ lives. Secondly, in promoting monetary metrics over more nuanced evaluations of the benefit and costs of human connectivity, they prioritise the visibility of certain achievements and ascribe more value to technical resources than to social co-ordination. These emphases contribute to inequalities within CNs, reinforce interdependence with capitalism and may unsettle cohesion in communities, and thus, I suggest, foreclose the opportunity for CNs to be sustainable alternatives to concentrations of telecommunications power.

Keywords

Community Networks; CNs; Commoning; WiFi; spectrum regulation;

Introduction

Over the past twenty years there has been intensified interest in Community Networks (CNs) as ways that rural communities without affordable access to telecommunications can autonomously ‘connect themselves’ to mobile telephony, a local intranet or the internet (e.g. Siochrú & Girard, 2005). Various organisations support rural inhabitants to establish their own CNs. Tech enthusiasts in not-for-profit initiatives teach rural people to set up and maintain networks; computing experts in universities experiment with technologies at rural sites; researchers of ICT for development (ICT4D) devise economic models to sustain CNs; and international coalitions advocate for policies and regulations that are more supportive of CNs and organise “the community network movement”. All the activities these groups do, and tools they use, are supported and controlled by a range of infrastructures that, as Susan Leigh Starr (1999) characterised, manifest certain institutional relations and reflect certain values and priorities. Infrastructures influence actions, define experience and shape the meanings we give to experiences (see: Dourish & Bell, 2007, Lampland & Star 2009). This article considers tensions between the meanings that technologists and activists associate with CNs when they foster and promote them, and meanings that reflect and constitute rural communalities. I propose that translating between these meanings can unsettle local social infrastructures that are imperative for CNs to sustain in rural communities.

My analysis synthesises insights from observing and engaging with rural CNs in the Global South and the CN movement over nearly ten years. This includes helping to set up CNs in Africa, multiple case research of CNs in Argentina, Mexico, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Uganda, and observing international advocacy for CNs. Because of the scope of this data, and the interdependencies of socio-technical infrastructure, I organize my account around two themes about translations that occur in infrastructuring CNs in the Global South. Thus, I restrict my literature review, next, to outlining key relationships in this infrastructuring, before summarising the experiences, methods and disciplines that shape my interpretations and illustrating practices of translating.

Infrastructuring Community Networks in the Global South

While definitions vary, there is some consensus that a CN must be owned by the community that deploys it, operate democratically, and actively involve local people in design, deployment and management (e.g. Internet Governance Forum’s Declaration of Community Connectivity, 2017). This definition holds more obviously for CNs in high income countries where tech enthusiasts initiate networks in the places where they live, and the population served by the CN has some familiarity with, and means to install, technology. In low and middle income countries where CNs might help to address exclusion from telecommunications, however, technical competency and resources are rarer; thus CNs are stimulated and supported by people who do not inhabit the places where they are sited.

Undoubtably there will be people in low and middle income countries that do set up rural telecommunications themselves, such as sharing WiFi hotspots but are unaware of, or do not identify with, the category ‘CNs’. In fact, in recent years, international civil society organisations have created a movement amongst CNs in diverse contexts to strengthen claims in lobbying governments to improve the legal and economic circumstances for CNs. For instance, the Internet Society (ISOC) a major non-profit that receives revenue from the .org domain names, and the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) recently funded the Fourth African CN Summit which supported 120 people involved CNs from over 30 African countries (www.internetsociety.org/events/summit-community-networks-africa/2019). As Chan (2007) describes for activism in Free/Libre Open Source (FLOSS), the concept of CNs can serve as a “boundary object” (Star & Griesemer, 1989) that has a common identity but also adapts to different local needs and constraints. FLOSS advocates in Peru built relations with established political actors in order to express a collective will to effect social and political change. CNs in our research about low and middle income countries had varied institutional models and included cases with relatively little involvement and sense of ownership by local inhabitants (Bidwell & Jensen, 2019). We referred to this diverse group of cases as CNs in the “Global South”. The vague yet homogenising term Global South (e.g. Milan & Treré, 2019; Toshkov, 2018; Chan, 2013), is not only used in international development discourse about digital exclusion in the Global North (e.g.: www.idrc.ca/en/project/understanding-digital-access-and-use-global-south), but also compatible with increased south-south collaboration and solidarity.

Since CNs in the Global South are often instigated and supported by people who do not inhabit the communities served by the CNs, their representation differs from FLOSS activism in Peru where actors do not claim authority to speak or act for others (Chan, 2007). In a survey of CNs in twelve African countries, Rey-Moreno (2017) found all 37 had links with Western institutions, including those with African founders. Some CNs are set up with seed funding from international organisations that pursue open access, such as the Open Technology Institute, a non-profit at the intersection of technology and policy (www.newamerica.org/oti/about/ ). Many CNs are stimulated by university collaborations; for instance, Filipino and US universities collaborated on deployments in isolated villages (Barela et al, 2018), and universities in Peru and Spain collaborate on networks in the Amazon (Rey-Moreno et al, 2011). While some associations between CNs and universities are part of internship or social responsibility programmes, more often they originate in or become part of academic research in computing, communication or international development studies which fund deployments and train local people (e.g. Jang et al, 2018; Backens et al, 2009; Mpala & van Stam, 2012). Thus, closer relationships tend to exist between particular representatives of CNs and organisations working on behalf of CNs, than between people within CNs’ grassroots communities in the Global South. Further CNs are integrated into centralized structures of legal and technical discourses and funding and research regimes.

Compared with analysis of CNs in the Global North (e.g. Crabu, et al, 2016), both academic and civil society research on CNs in the Global South focus on technology and models of sustainability as quite narrowly bounded artefacts. Over half the 44 articles in a recent book on CNs focused on technologies as material artefacts, technical skills and/or technical regulatory issues (see: Association for Progressive Communications, 2018). CNs provide opportunities for technologists to experiment with, for instance, open, distributed infrastructure (e.g. Braem et al, 2013), TV White Space technologies (e.g. Hadzic, et al 2016), or user interfaces (e.g. Jang et al, 2018). Technological emphases in civil society and academic accounts about CNs in the Global South tend to restrict the word ‘infrastructures’ to the hardware and software components, architectures and interfaces that comprise technological networks (e.g. Plagemann, 2008; Khan et al, 2013; Fuchs, 2017). While technologists aim to localise technical agency and assist rural inhabitants to set up their own CNs, these accounts they do not explore the politics, values, practices and relations hidden in the socio-technical arrangements that make CNs. Their accounts show, as Dunbar-Hester (2016) explains for media and broadcasting projects in East Africa, that they enact certain boundaries which distribute and order certain rights and responsibilities between “the technology” and “the social”.

CNs in the Global North are motivated to decentralise telecommunications and oppose concentrations of power (De Filippi & Treguer, 2015). Their members perform, Crabu & Magaudda (2018 p22) suggest, “’a kind of ‘artful infrastructuring’ of technologies, organizational models and political visions into an effective participatory process of technology development”, and develop convergent political views and practices, based in leftist and anti-capitalist movement. Yet difficulties arise in redistributing power when tech enthusiasts introduce community networking, and other projects to decentralize media, in outreach to people who are digitally excluded (Dunbar-Hester, 2009), which may undermine creating authentic local participation, adoption and appropriation (see: Le Dantec and DiSalvo, 2013). In fact, De Filippi and Treguer (2015) observe that the history of communication technologies is replete with cases in which concentrated clusters of power progressively evolved from originally decentralised, sometimes subversive structures.

In fostering CNs in Global South, technologists and activists combine commitments to opposing concentrations of power with more utilitarian pursuits to democratise communication and information access (see: Association for Progessive Communications, 2018). The ways their practices integrate with the infrastructures of legal and technical discourses and funding and research regimes may, however, undermine inclusion. Consider, for instance, how the “nuts and bolts” and “geeky” identities of CNs that inhibit inclusion in the Global North (Jungnickel, 2013; Dunbar-Hester, 2010) affect CNs in the Global South. My analysis, of data in the same set also presented in this article, shows that while advocacy for CNs assumes that short-range wireless technologies and their conventions are gender-neutral, they are often incompatible with constraints on mobility which limits women’s access and involvement in CNs in the Global South (Bidwell, 2019). Zanolli et al (2018) describe feminist infrastructuring work that aims to create CNs in Brazil that foster relationships between “non-hegemonic groups” by pursuing objectives that not prioritised in many CN projects. In this article I propose that meanings in rural communities that are imperative for CNs to sustain in the Global South are abandoned when they are translated through universalising technocratic infrastructures. Before describing the data that supports this claim, I explain the scholarly traditions that inform my perspective on meanings and translation.

Situating insights

My analysis is situated in the “third-paradigm” of the field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI) (e.g. Harrison et al, 2011) and the allied discourses of Participatory Design (PD) and Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). HCI’s third-paradigm integrates technology design with social and cultural analysis, drawing on social sciences, Science and Technology Studies (STS) and critical theories, such as feminism and postcolonial computing. My orientation to these frames and theories is shaped by phenomenology. I consider meaning to be situated in specific, often collaborative, contexts, adaptive to a world that is constantly in flux and irreducibly connected to view-points, interactions, histories and the resources to hand. My analytic engagements do not claim objective detachment and, indeed as I next explain, my work over the past decade combines technology interventions in southern Africa, including setting up CNs, and ethnography to inform and reflect on these interventions.

Socio-Technical Interventions

My engagement with CNs began in South Africa’s rural Eastern Cape, although for the first three years I was unaware of the term ‘community network. In 2008 I undertook ethnography while living in a village (Bidwell, 2009) and my insights and relationships inspired installing WiFi between the headmen who oversee three villages. This WiFi did not sustain, however insights from its failure and my longer term action research in the area over the next 3-years (Bidwell, 2010, Bidwell et al, 2010, Bidwell et al 2013, Bidwell & Siya, 2013, Bidwell, et al 2014, Bidwell, 2016) scaffolded the emergence of a CN (e.g. Rey-Moreno et al, 2012, 2013, 2015). I promoted CNs when I moved to Namibia in 2014, with workshops at an international conference and presentations at a National IT summit. In 2015, I gained funding for a Namibian NGO’s rural WiFi and also mentored a student to start a CN in a village near my home (Louw et al, 2018). Since then I assisted a bid for women-driven CNs in Africa (www.afchix.org/afchix-announced-as-one-of-usaids-womenconnect-challenge-winners/), ran workshops introducing women to CNs in Ghana and participated in regular discussions about CN projects through the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) (e.g. www.apc.org/en/news/meet-projects-funded-catalytic-intervention-grants-create-more-sustainable-community-network).

Multiple Case Research

At the end of 2017 the APC contracted me to study relationships between social, gender, economic, political and ICT factors in people’s access to, use of, and interactions with their local CN in the Global South. As detailed in Bidwell and Jensen (2019) my research focused on six rural cases in Argentina, Mexico, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Uganda. As common for CNs globally, most cases use low cost equipment operating in license exempt frequencies. One case provides GSM-based voice and SMS services, and the others variously provide WiFi-based internet connectivity to local authority offices, households and public hotspots. Local community involvement in the CNs, the influence of local authorities and their relationships with the people in the local community varied (Bidwell, 2020a).

A total of 152 women and 172 men participated in observations, focus groups discussions (FGDs) and interviews, recorded by audio and, when participants permitted, video. I also observed participants’ interactions with each other and with documents, equipment and other objects in settings and made records of interfaces to applications and systems comprising the CN, sign-in books, manuals, posters and signs. Observations included specific activities, such as a workshop for local operators of CNs hosted by a support organisation, and when I participated in informal activities. Over 80% of interactions were mediated in seven local languages and translated into English, simultaneously whenever feasible.

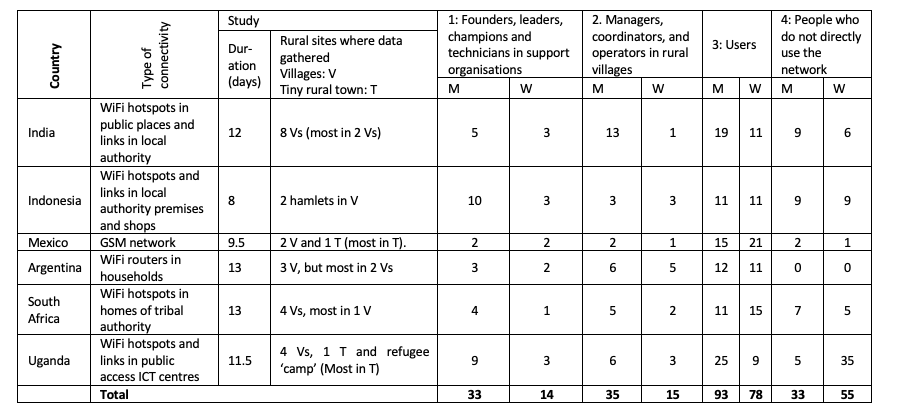

A total of 50 participants were initiators, leaders, champions and technicians in support organisations, who did not live in the rural areas in which CNs are deployed (Participant Type 1 in Table 1). The remaining 274 participants inhabit the rural villages or small towns in which the CNs are deployed and can be broadly grouped into three overlapping, Types: (2). Managers, coordinators, volunteers and operators; (3) users of CNs in rural villages; and, (4) non-users, or people who have not used it directly themselves because they cannot or chose not to, or because other people mediate their interactions. Most participants of Types 2, 3 and 4 live in the same or nearby villages, except in Uganda and India where cases included many more sites; thus, while I do not identify participants or village names, anonymity is often impossible at a local level. To gain insights into different dimensions that might shape access to and involvement in CNs, I sought to include people with diverse characteristics and equal numbers of women and men in all categories. Men, however, constituted over 70% of founders, initiators or champions and workers in support organisations, and women comprised 65% of non-users in villages. I sought to separate interviews and FGDs with men and women but rarely achieved this and less than a third of the 34 small or large FGDs included only women participants and interpreters.

Table 1 Numbers of people participating in different categories across studies in the multiple case research

Observations of Advocacy and Movement Building

As well as my multiple case research, the APC’s “LocNet” team studied technologies and business-models deployed by CNs and policies affecting CNs, prototyped technologies, liaised with CNs, civil society groups and regulatory authorities globally, and responded to consultation about regulatory frameworks. Our team, of two women and five men, had extensive experience in technology in the Global South, and like me, three of the men had, also founded CNs. As we lived in Africa, Mexico, Canada and Portugal we met only at the project’s inception, a year later and at the conclusion of my study. In between we regularly met online to update on our research and advocacy, and posted materials about topics related to policy, technical advances and impacts to dedicated Slack channels. Our lively discussions encouraged different perspectives and integrated ongoing insights into actions.

I was also involved in the first African Summit on CNs in 2016, attended the fourth African Summit on CNs Summit in 2019 and participated in the associated WhatsApp group. I have also fostered links between CN practitioners and researchers in Asia, Africa and Latin America, participated in fora about CNs at the International Governance Forums (IGF) in Paris and Berlin in 2018 and 2019, and recently launched an initiative about communities local stories about CNs.

Analysis

I synthesise insights accrued in my interventions, multiple case research and observing advocacy into two themes about translations that occur when activists and technologists promote and support CNs in the Global South. My account describes how these translations make practices that produce CNs into things and ascribes these things certain values and then some of the consequences of this translating.

Translating Commonings to Common Things

To avoid costly cables over long distances rural CNs generally involve wireless transmission, such as WiFi and occasionally GSM, and must apply to regulatory authorities to purchase, or gain exemption from, licenses to use spectrum. Advocates for CNs argue that market-based approaches, which treat spectrum as property and grant licenses for exclusive use of certain frequencies in a specific geographic area, do not serve rural and low-income people (e.g. Rey-Moreno et al, 2015). For instance, assignments of GSM spectrum go unused in low-income rural areas in South Africa because a few telecom companies value-price cellular and broadband services for markets, usually in urban areas, that can afford their tariffs (Avila, 2009, Bhagwat et al, 2004). While governments control spectrum, telecom companies collaborate to maintain high prices and influence policy and regulation, and authorities are often lenient on regulated firms, which has led to allegations and cases of “regulatory capture” throughout the world (De Filippi & Treguer, 2015). Thus, as claims for democratic access to telecommunications have argued for over a century (Wong & Jackson, 2015), international advocacy calls for commons-based approaches that permit CNs to use spectrum in some bands without licenses.

In arguing for commons-based approaches, activists often adopt a metaphor that pervades technical and regulatory perspectives by likening spectrum to land (Wong & Jackson, 2015). Common resources, of course, take diverse forms, including physical entities, and intellectual and cultural products that can or cannot be fenced or bound, such as land, water, music, software; and, intangible social goods such as care for the elderly. Access to spectrum must, however, be managed to make it operable. Thus, the land metaphor has become normalised in unlicensed approaches (e.g. Song et al, 2019), even though is more contiguous with assumptions about private property in market-based approaches. A land metaphor can be convenient in discussing spectrum licenses and other aspects of configuring CNs with rural communities whose everyday realities involve sustaining livelihoods by managing environmental resources together. Traditions and public expectations of collaboration and consensus in managing communal resources anchored setting up and operating WiFi in the South African CN (Rey-Moreno et al, 2012), where rural inhabitants share access to forests and pasture, and their tribal authority allocates land for homes among families (see: Bidwell et al, 2013). Similarly the right to own land in the Mexico case, where an indigenous community owns and manages its own low-cost, open source GSM base-station, requires households to participate in the traditional assembly and in communal work. Sometimes local concepts about land respond to colonisation, where indigenous people’s make claims in order to exercise traditional responsibilities to care for environmental interrelations rather than own terrain or territory. Local governance arrangements that link sovereignty and self-determination to land provide a context for discussing how a CN operates according to a shared commitment with some agreed rules, and the land metaphor can appeal to citizens that oppose privatisation of rights to resources. For instance, indigenous participants in the Mexican CN mentioned threats to water, and some participants in Argentine CNs protest mining initiatives.

While the land metaphor may serve as a “boundary object”(Star & Griesemer, 1989) in discussing spectrum and licenses with rural communities it is not without ambiguity or contestation. Indeed the metaphor illustrates problematic naturalised meanings that might undermine opportunities for local infrastructuring. Just as land became an thing to communities in the face of colonisation, spectrum has also been made a thing. The founder of an organisation supporting the Mexican CN, and part of our APC project team, suggests spectrum is a potential:

“the potential to communicate over the airwaves. It has been turned into a thing in order to extract value from it and assign its use in an orderly fashion. These two visions (thing vs. potential) conflict when communities want to use spectrum to communicate how they see fit”. (APC News, 2018).

Yet spectrum is as much a practice (Streeter, 1996) as a potential to communicate or a thing to slice up; and, it is not inevitable that commodification accompanies its reification (thingification). Reifying deemphasises the social processes that are, as Elinor Ostrom (1990) notes, integral to common pool resources, such as spectrum. The potential use of electromagnetic radiation to communicate exists only in social collaboration, thus “users” to whom parts of spectrum are allocated are envisaged as organisational entities, such as national telecommunication providers, and “complementary” or “small-scale” operators. Constructing use according to certain types of organisations, however, makes many practices of spectrum invisible by encapsulating them and focusing only on certain practices in realising the potential of spectrum for communicating.

Physical resources, such as land, are often a reference for collective efforts towards a common goal, but bounding them into entities obscures that commons are not simply found and used but rather produced through social practices. For instance, expectations of communal participation and volunteer work are integral to land in the Mexican and South African communities where people produce, reproduce, circulate and exchange diverse resources, including intangible social goods like care, in managing other resources; and cohesion can be unsettled when certain resources gain precedence. The role of social processes in the commons has led to contemporary theoretic emphasis on practices of ‘commoning’, that entwine production and use in reproduction of the commons (e.g. Fournier, 2013). However, in supporting communities that are developing CNs, explanations often focus on things; for instance, workshop facilitators in an support organisations helped participants visualise the values, that their network is based on, with lines to connect together points on a large paper graphic. This focus emphasises connections rather than the practices that make and sustain connections. A focus on things and connections, rather than acts that make connections distracts from the social fabric of a CN. A connection within a telecommunication network can be decomposed into a fairly instantaneous event, however, commoning involves acts of connecting that are embedded in the ongoing trajectories of people’s lives. The Argentine CNs illustrated, for instance, that newcomers and people whose families have lived in the area for generations connect through their interactions with their CNs (Bidwell, 2020b). The nuances and dynamics of the cohesion that is critical to community cannot be reified as a static resource, like land, or visualised by drawing lines to join together values.

Most advocates for CNs and the workers in in my multiple case research were sensitive to the complicated social relations that CNs involve. However, their interactions with rural dwellers were usually remote, as resource constraints restricted frequent trips and they sought to foster autonomy and self-reliance in communities with respect to their CNs. The distance between most support organisations and the ongoing acts that comprise the social fabric of rural CNs further encourages focusing on common things rather than commonings, or constructs that are inseparable from local human relationships or tasks. Participants from different CNs in Africa and Latin America vigorously and repeatedly mentioned that the temporalism of ongoing community relations is unsettled when external schedules and timelines, are imposed. We certainly experienced this in Namibia. For the first three years our CN was self-funded, depended on a mule system to share previously downloaded content, then shared a community member’s internet connection (Louwe et al, 2018). In 2018, a start-up provided a better base station and ran workshops to assist inhabitants in developing content, we obtained a small grant to buy equipment and joined a pan-African project that funds workshops and a stipend for a local coordinator. After evolving according to local timescales and resources, we became accountable to constructs of time associated with funding and the deadlines that this introduced created tensions in the very relationships that had sustained the CN for so long. Thingifying activities in time into milestones can reorient CNs away from their community origins.

Translating Production through Market Logics

Advocates often justify CNs in the Global South according to models of sustainable development that promote monetary metrics over alternative evaluations of benefits and costs of human connectivity. Their recommendations for regulatory and policy environments to enable CNs are predicated on economic arguments; asserting, for instance, that opening up markets will encourage more operators to address the needs of underserved, that competitive pressure to reduce data costs yields industry growth (e.g. Huerta, 2018) and extoling “the power of frictionless innovation” (Song et al, 2019). Assumptions that capitalist structures and market logics are inevitable are reproduced in practices that introduce CNs to communities, which relate sustainability to business. For instance the “business model canvas”, a tool that is widely applied in social enterprises, featured in all four international programmes for CNs I observed in the past year. The categories the model applies, such as “customer segments”, “cost structure” and “revenue streams”, construct CNs in monetary ways and make invisible practices of commoning, such as sharing. Indeed, emphasis on economic drivers and impacts neglects the practices of community on which a CN is based.

Meanings about communality featured in interviews and discussions for five of the six cases I studied (Bidwell & Jensen, 2019). Participants mentioned many examples of assisting others in communication or accessing information, from setting up others’ access, facilitating messages or a call on WhatsApp for people without access, and using online services on others’ behalf. Women in the Indonesian case, for instance, explained that since few of them owned phones they communicated with each other by sending and receiving messages through neighbours; meanwhile, some elders in the cooperative that manages the South African CN cannot use their own phones to access the internet but still tried to help others connect to the WiFi. Some CNs manifested existing collectivist principles, and others were a vehicle to foster solidarity. The CNs in South Africa and Mexico are founded on customary governance structures, ancestral and family ties and communal values. Some Mexican participants said they supported the CN because it enabled access to disadvantaged inhabitants not because it enhanced their own access to telecommunications, and many referred to local people’s work in setting up their CN together. Argentine CN members said that the CNs’ communal characteristic bridge between different parts of local society, such as intergenerationally and referred to cooperative traditions and solidarity movements (Bidwell, 2020b). The Ugandan case seeks to re-establish unity in communities where war and post-conflict actions scattered and destabilised communities, undermined people’s trust in institutions, neighbours and even family members, and contributed to youth unemployment and disaffection. Its founder prioritised peaceful coexistence in all activities by emphasising traditional practices of coming together in dialogue to manage disputes, such as about land or water, and this was reiterated youth who said they sought to share their individual talents to help each other.

While practices of commoning, such as helping others to communicate, may be integral to community stability, the practices that introduce CNs tend to ascribe value to certain tasks. In the support organisations I studied both employees in technical and coordination roles were paid. Yet, within villages payment was usually only for computer-based and technical tasks. In the six cases I spoke to people in 84 explicitly recognized roles in CNs and support organisations, from network administrator to cooperative secretary, that did some kind of recognized work in maintaining their respective CNs. “Work” was more likely to be recognised if it involved technical tasks; further, while half of the 51 roles that involved technical tasks were remunerated, only a quarter of the 33 other roles were. The network administrator in Mexico, for instance, receives a small stipend, a young woman is paid to manage subscriptions to the WiFi in Indonesia, and in South Africa both of the two local roles that are paid through the support organisation’s budget are primarily or partly technical. Facilitating people in rural communities in developing technical skills, aims to challenge expert-based, decision-making. While, of course, technical people who develop software and hardware or install and maintain the equipment for CNs are essential, the potential for communication within a CN is equally realised by a great variety of people who contribute other resources that enable management, organisation and use. Indeed, members of the Argentine CNs noted the importance of competences in managing complex social relationships, and that more time is spent coordinating to enable people could undertake tasks together, and preparing all the necessary equipment, than actually undertaking technical tasks (Bidwell, 2020b).

Translating the benefits and costs of human connectivity through market logics and monetary metrics has paradoxical consequences for CNs. The translation reinforces an interdependence of CNs with capitalism, contributes market relations to commoning and, by conflating with demographics and gender issues, undermines the labour available to maintain CNs. Generating income motivated people’s involvement in the South African, Indonesian and Indian CNs, such as providing them or their children with paid employment. In South Africa this created tensions around the type of activities that warranted remuneration, such as attending meetings, charging people’s cell phones or selling subscriptions, and in Indonesia middle aged women explained that younger people had disengaged from communal activities and were increasingly drawn to profit sharing initiatives associated with the WiFi. Further, local gendered power relations, where women undertake much of the volunteer labour (Shewarga-Hussen et al, 2016, Bidwell, 2019), conflate with valorisation and monetisation of technical tasks. I spoke to 36 men and 15 women in support organisations or CNs at village level who undertook technical tasks, and of these 25 men but only 8 women were paid. There are, respectively, more and significantly more women than men in rural South and East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, 2011; International Labour Organisation, 2010) and globally the proportion of women in rural areas is increasing, especially in older age group (Worldbank, 2018). Indeed, in several cases I studied, migration led to a high turnover of men who were trained to undertake technical tasks, which suggests that close ties with labour markets may not offer CNs long term sustainability.

Conclusion

The infrastructures of technology and international development research and funding and telecommunications regulation shape the meanings made by technologists and activists who advocate that CNs can improve rural connectivity in the Global South. Even when they oppose concentrations of power and seek to democratise communication they employ certain constructs and models that are infrastructures “at the centre” (Chan, 2013). Translating these constructs and models in rural communities may excise local meanings that are vital to sustainable and inclusive CNs. Ostrom (1990) argues that theorists foreclose the possibility of alternatives to the tragedy of the commons because they do not account for specific local social relations. Likewise, I propose that technologists and activists foreclose the possibility of alternatives to concentrations of telecommunications power by inadvertently keeping meanings that emerge in social relations in rural communities at the periphery. Reifying practices, such as connections, distracts from the ways a CN’s fabric is embedded in the ongoing trajectories of inhabitants’ lives. Bounding the resources used and produced in CNs into static entities, that can be charted into the elements on a business model and assessed as impacts, excises the nuances and dynamics of commoning, such as practices of trust, reciprocating and cooperating.

When activists apply language that commodifies, in advocating regulations and policy that are conducive to CNs, they contribute to normalising constructs about sustainability which associate particular values with technical resources. The incompatibility of market economy measures of use and impact in community telecommunications has been discussed for low-power FM (LPFM) broadcasting in the Global North. Dunbar-Hester (2014) richly describes how market-based metrics do not express the locally relevant and appropriate value of local production and content that community radio stations bring, especially to poorer communities. My account describes some of the ways that monetisation of technical resources brings market relations to practices of commoning. Cohesion in communities may be unsettled when certain resources gain precedence. Selectively valorising technical tasks in producing the commons not only deemphasises benefits of CNs, such as the sense of empowerment that rural people might gain (Bidwell and Jensen, 2019), but also reproduces local inequalities, for instance by conflating the value of certain tasks with gendered labour (Bidwell, 2019). Valorising technical work and devaluing nontechnical work, which is more likely to be performed by women, is similar to observations of community radio in the Global North. Dunbar-Hester (2014) describes how the gendered identities of tasks both exclude women from technical tasks and create tensions if women eschew the traditional gender roles through which other women derive authority and perform solidarity. Nightingale (2019) explains strong communitarian relations do not inevitably result in inclusion and power relations are embedded in processes of commoning. She recommends constant vigilance and adjustment of everyday acts of commoning to address exclusion, which is impossible when support organisations are located far from the social fabric of rural CNs and operate through existing rural power structures (Bidwell, 2019). Infrastructuring is an ongoing process and not delimited to designing or setting-up participatory projects (see: Dantec and Carl DiSalvo, 2013), thus to foster a more “artful infrastructuring” (Crabu & Magaudda, 2018). I advocate for activists and technologists to spend longer in communities learning about all the specific ways commonings, not common things, are reproduced.

Acknowledgements

I thank all participants for their generosity and the APC and LocNet team for their support. The multiple case research and advocacy was carried out with the APC with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors. I finalised this article as part of the Grassroot Wavelengths Project which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 780890.

References

APC News ( 2018) What’s new on the spectrum? “Let’s make sure we can use it for what is needed”: A conversation with Peter Bloom from Rhizomatica. Available at: www.apc.org/en/news/whats-new-spectrum-%E2%80%9Clets-make-sure-we-can-use-it-what-needed%E2%80%9D-conversation-peter-bloom

Association for Progressive Communications (2018) Global Information Society Watch: Community Networks. APC Press. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/global-information-society-watch-2018-community-networks

Avila (2009) Underdeveloped ICT areas in Sub-Saharan Africa. Informatica Economica, 13(2). pp.136–146.

Backens, J., Mweemba, G, and Van Stam, G. (2009) A rural implementation of a 52 node mixed wireless mesh network in Macha, Zambia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Infrastructure and e-Services for Developing Countries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg,

Barela, M.C., Dionisio, J. Heimerl, K., Sapitula M., and Festin, C.A. (2018) Connecting Communities through Mobile Networks: The Vbts-Cocomonets Project. Global Information Society Watch: Community Networks. APC Press. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/global-information-society-watch-2018-community-networks

Bhagwat, P., Raman B., and Sanghi, D. (2004) Turning 802.11 inside-out. SIG- COMM Comput. Commun. Rev. (34). 1 (pp 33-38). ACM Press.

Bidwell, N.J. (2009) Anchoring Design to Rural Ways of Doing and Saying. In Proceedings of INTERACT’09. IFIP & Springer-Verlag: Lecture Notes in Computer. Science. Pp 686 – 699.

Bidwell, N.J. (2010) Ubuntu in the Network: Humanness in Social Capital in Rural South Africa. Interactions 17(2) pp 68-71

Bidwell, N.J. (2016) Moving the Centre to Design Social Media for Rural Africa. AI&Soc: Journal of Culture, Communication & Knowledge, 31(1) pp 51-77. Springer.

Bidwell, N.J. (2019) Women and the Spatial Politics of Community Networks. In Proceedings of 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction (OzCHI’19). ACM Press.

Bidwell, N.J. (2020a) Women and the Sustainability of Rural Community Networks in the Global South. In Proceedings of International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (ICTD 2020) Ecuador. ACM Press.

Bidwell, N.J. (2020b) Wireless in the Weather-world and Community Networks Made to Last. In Proceedings of the Biennial Participatory Design Conference. Colombia (PDC2020). ACM Press.

Bidwell, N.J. and Jensen, M. (2019). Bottom-up Connectivity Strategies: Community-led Small-scale Telecommunication Infrastructure Networks in the Global South. APC. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/bottom-connectivity-strategies-community-led-small-scale-telecommunication-infrastructure

Bidwell, N.J., Reitmaier, T., Marsden G. and Hansen, S (2010) Designing with mobile digital storytelling in rural Africa. Proceedings of 28th International Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM Press. 1593-1602.

Bidwell, N.J., Reitmaier, T. and Jampo, K. (2014) Orality, Gender & Social Audio in Rural Africa. In Proceedings of 11th International Conference on the Design of Cooperative Systems, France. Springer.

Bidwell, N.J. and Siya, M.J. (2013) Situating Asynchronous Voice in Rural Africa. In Proceedings of INTERACT’13. International Federation for Information Processing IFIP & Springer-Verlag: Lecture Notes in Computer. Science: pp 36–53.

Bidwell, N.J., Siya, M.J., Marsden, G., Tucker, WD., Tshemese, M., Gaven, N., Ntlangano, S., Eglinton, KA Robinson, S. (2013) Walking and the Social Life of Solar Charging in Rural Africa. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) (20)4: pp 1-33.

Braem, B., Blondia, C., Barz, C., Rogge, H., Freitag, F., Navarro, L., Bonicioli, J., Papathanasiou, S., Escrich, P., Baig Vinas, R. and Kaplan, A.L. (2013) A case for research with and on community networks. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 43(3), pp.68-73.

Chan, A. S.(2007) Retiring the Network Spokesman: The Poly-Vocality of Free Software Networks in Peru. Science Studies 2

Chan, A. S (2013) Networking Peripheries. Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Crabu, S., Giovanella, F., Maccari, L. and Magaudda, P. (2016) A transdisciplinary gaze on wireless community networks. Tecnoscienza: Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies, 6(2), pp.113-134.

Crabu, S. and Magaudda, P. (2018) Bottom-up infrastructures: Aligning politics and technology in building a wireless Community Network. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). 27(2) pp 149-176.

De Filippi, P. and Tréguer, F. (2015) Expanding the Internet commons: The subversive potential of wireless Community Networks. Journal of Peer Production, (6)

Dourish P. and Bell G. (2007) The infrastructure of experience and the experience of infrastructure: meaning and structure in everyday encounters with space. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34( 3) pp 414-430.

Dunbar-Hester, C. (2009) Free the spectrum!: Activist encounters with old and new media technology. New Media & Society, 11(1–2) pp 221–240.

Dunbar-Hester, C. (2010) Beyond “dudecore”? Challenging gendered and “raced” technologies through media activism. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media (54)1: pp 121-135.

Dunbar-Hester (2014) Low power to the people: Pirates, protest, and politics in FM radio activism. MIT Press.

Dunbar-Hester, C. (2016). Frailties at the Borders: Stalled Activist Media Projects in East Africa. International Journal of Communication, 10, p.22.

Fournier, V. (2013). Commoning: on the social organisation of the commons. M@n@gement 16(4), 433-453. Available: www.cairn.info/revue-management-2013-4-page-433.htm#

Fuchs, C. (2017). Sustainability and Community Networks. Telematics and Informatics 34(2): pp 628-639.

Hadzic, S., Phokeer, A. and Johnson, D. (2016). TownshipNet: A localized hybrid TVWS-WiFi and cloud services network. IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS). IEEE

Harrison, S., Sengers, P. and Tatar, D. (2011). Making epistemological trouble: Third-paradigm HCI as successor science. Interacting with Computers, 23(5), pp.385-392.

Huerta, E. (2018). Legal framework for community networks in Latin America. Global Information Society Watch: Community Networks. APC Press. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/global-information-society-watch-2018-community-networks

International Labour Organisation, ILO (2010) Gender dimensions of agricultural and rural employment: Differentiated pathways out of poverty – Status, trends and gaps (Rome, 2010).

Internet Governance Forum. 2017 Outcome Document on community connectivity: declaration on community connectivity. Available: www. Intgovforum.org/multilingual/index.php?q=filedepot_download/4189/174

Jang, E., Barela, M.C., Johnson, M., Festin, C., Lynn, M., Dionisio, J and Heimerl. J (2018). Crowdsourcing Rural Network Maintenance and Repair via Network Messaging. In: Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’18). ACM Press

Jungnickel, K. (2013). DIY WiFi: re-imagining connectivity. Springer,

Khan, A. M., Navarro, L., Sharifi, L., and Veiga, L. (2013). Clouds of small things: Provisioning infrastructure-as-a-service from within Community Networks. In Proceedings of IEEE 9th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob). 16-21. IEEE.

Lampland, M. and Star. S.L. (2009). Standards and their stories: How quantifying, classifying, and formalizing practices shape everyday life. Cornell University Press.

Le Dantec, C A. and DiSalvo. C (2013). Infrastructuring and the formation of publics in participatory design. Social Studies of Science 43.2: 241-264.

Louw, Q., Coffin, J. and Muller, C. (2018). Namibia: The Seed of a Community Network. Global Information Society Watch 2018: Community Network. APC. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/global-information-society-watch-2018-community-networks

Milan, S. and Treré, E. (2019). Big Data from the South(s): Beyond Data Universalism. Television & New Media, 20(4), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419837739

Mpala, J. and van Stam. G. (2012). Open BTS, a GSM experiment in rural Zambia. In Proceedings International Conference on e-Infrastructure and e-Services for Developing Countries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Nightingale, A. J (2019). Political Communities, Commons, Exclusion, Property and Socio-Natural Becomings. International Journal of the Commons 13(1) pp. 16–35.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Plagemann, T., Canonico, R., Domingo-Pascual, J., Guerrero, C. and Mauthe, A. (2008) Infrastructures for community networks. In Content Delivery Networks (pp. 367-388). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Rey-Moreno, C. (2017) Supporting the Creation and Scalability of Affordable Access Solutions: Understanding Community Networks in Africa. The Internet Society May 2017, Available: www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2017/supporting-the-creation-and-scalability- of-affordable-access-solutions-understanding-community-networks-in-africa/

Rey-Moreno, C., Bebea-Gonzalez, I., Foche-Perez, I., Quispe-Tacas, R., Liñán-Benitez, L., and Simo-Reigadas, J. (2011) A telemedicine WiFi network optimized for long distances in the Amazonian jungle of Peru. In Proceedings of the 3rd Extreme Conference on Communication: The Amazon Expedition 9. ACM press.

Rey-Moreno, C., Roro, Z., Siya, M. Simo-Reigadas, J., Bidwell, N.J., Tucker, B. (2012). Towards a Sustainable Business Model for Rural Telephony. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop about Research in ICT for Human Development. July 2012, Cuzo, Peru.

Rey-Moreno, C., Roro, Z., Tucker, W.D. and Siya, M.J. (2013) Community-based solar power revenue alternative to improve sustainability of a rural wireless mesh network. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communications Technologies and Development: Notes-Volume 2 (pp. 132-135). ACM press.

Rey-Moreno, C., Tucker, WD., Cull, & Blom, R. (2015). Making a Community Network legal within the South African regulatory framework. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (p. 57). ACM Press.

Shewarga-Hussen, T., Bidwell, N.J., Rey-Moreno, C., Tucker, W.D. (2016) Gender and Participation: Critical Reflection on Zenzeleni Networks. In Proceedings of the 1st African Conference for Human Computer Interaction (AfriCHI’16). Nairobi, Kenya, ACM Press.

Siochrú, S.Ó. and Girard, B. (2005) Community-based Networks and Innovative Technologies. United Nations Development Programme.

Song, S., Rey-Moreno, C., and Jensen, M. (2019) Innovations in Spectrum Management. Enabling Community Networks and small operators to connect the unconnected. The Internet Society. Available: www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2019/innovations-in-spectrum-management/

Star, S.L. (1999) The ethnography of infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43(3)377-391.

Star, S.L. and Griesemer, J.R. (1989) Institutional ecology, translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social studies of science, 19(3), 387-420.

Streeter, T. (1996) Selling the air: A critique of the policy of commercial broadcasting in the United States. University of Chicago Press.

Toshkov, D. (2018) The Rise of the Global South. Research Design Matters Available: http://re-design.dimiter.eu/?p=969

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2011) Rural Women and the Millennium Development Goals 2011 http://www.fao.org/3/an479e/an479e.pdf

Wong, R.Y. and Jackson, S., (2015) Wireless visions: Infrastructure, imagination, and US spectrum policy. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing 105-115. ACM Press.

Worldbank (2018) The World Bank Data on Rual Populations

Zanolli, B., Jancz, C., Gonzalez, C., Araujo dos Santos, D. and Débora Prado, D. 2018 Feminist infrastructure and Community Networks, Global Information Society Watch 2018:Community Networks. APC Press. Available: www.apc.org/en/pubs/global-information-society-watch-2018-community-networks