Keywords:

air pollution in China, resistance, pollution activism, citizen science, public participation

by Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez

Abstract

This article discusses how China’s new era of air pollution control provoked groups of urban residents and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) to adopt citizen science and strategies for disseminating technoscientific knowledge. Since 2008, their actions have included sharing photographic records, posting scientific evidence online, testing air purifiers and air pollution masks, and reporting data results from low-cost sensors. Interviews with the leaders of these initiatives show the changing patterns of pollution activism and engagement in the country, appealing to civic and resistance approaches to technoscientific knowledge and practices. Following and articulating recent works on STS about citizen science as resistance and Chinese studies on pollution activism, this article presents the civic adoption of scientific knowledge and technological devices as instrumental to activists but also problematic to navigate in the complex participative context of the country. The dynamism of the actions, first marked by the mistrust of official data and then expanding to other agendas, brings about a novel approach to resistance in the context of the environmental health crisis in China.

Keywords: air pollution in China, resistance, pollution activism, citizen science, public participation

Introduction

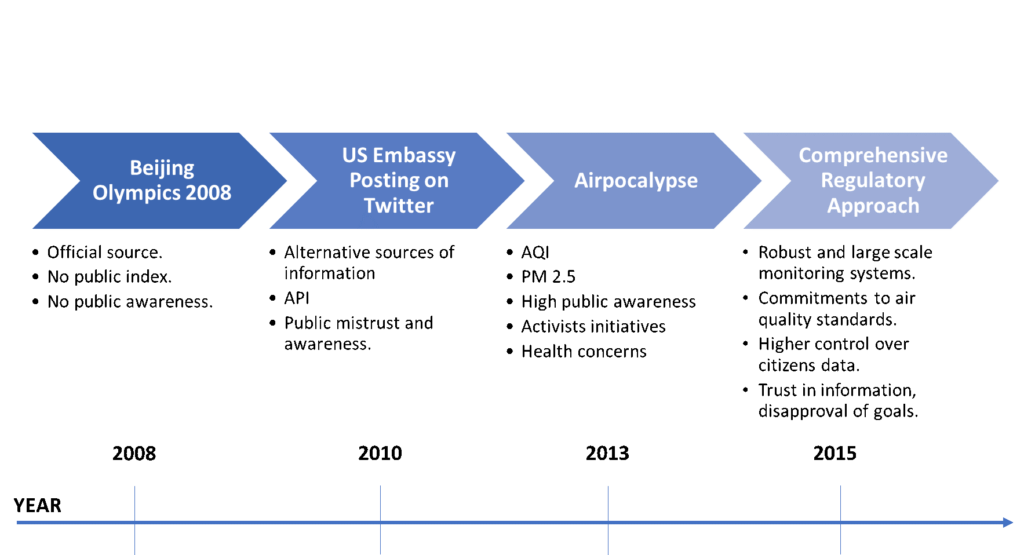

The year 2008 brought the Summer Olympics (hereinafter ‘the Olympics’) to Beijing and inaugurated a new kind of government approach to, and citizen awareness of, air pollution that spread around the country. The commitment of the central and local governments to the International Olympic Committee to clear the skies during the sporting event was echoed by political statements and media coverage, formalizing the start of an era of regulatory and control measures. Chinese citizens, who in the past had only a slight concern about air quality and some notion of its official management, started to share more information about the problem, which raised questions about health effects, monitoring technologies, and public data.

In the years after the Olympics, public mistrust gained momentum, in part because the government was reluctant to qualify information, due to episodes of high pollution that affected main cities. Some NGOs and start-ups, as well as groups of netizens and academics, supported citizens’ demands by adopting diverse strategies to provide information about air quality standards and pollutants, epidemiological studies on health issues, air purifiers and protection masks, and cheap testing and sensor devices. These actions focused on how to bypass government censorship and effectively spread messages to citizens. These groups of people found that sharing scientific evidence and academic sources online, and offer advice about personal care and air quality products, were ways to lessen the political attention of authorities. During this process, they generated changes in the political role of citizens towards air pollution, which resulted in public attention being focused on air quality monitoring systems and regulatory standards (Ho & Nielsen, 2013; Lin & Elder, 2014; Zhao et al., 2015).

This article analyses China’s air pollution awareness through the eyes of public participation, citizen science, and the popularization of air quality knowledge. Theoretically, it articulates two areas of study, Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Chinese Studies, and specifically the growing attention being paid to the intersections between environmental activism and technoscientific knowledge. From the side of STS, this article advances efforts to understand local environmental governance (Jasanoff & Martello, 2004) by discussing how the civic use of technoscientific knowledge (Corburn, 2005; Fortun & Fortun, 2005; Jalbert, 2016; Wylie et al., 2014) can provide public participation with elements to interact and shape experts’ discourse and policy circles (Yearley, 2006; Yearley et al., 2003). According to Kullenberg (2015) and Ottinger (2010a), contexts with few spaces for participation, open data, and deliberation have produced a type of “citizen science as a resistance”, which confronts, in diverse ways, power and closeness values regarding the rights of information. On the side of Chinese Studies, the article approaches debates about environmental citizen activism (Lora-Wainwright, 2013; Van Rooji, 2010), offering new arguments about how Chinese activists build safe spaces for participation and leveraging the common approach of the official domestication of activism (Ho & Edmonds, 2008; Li & O’Brien, 2008). The diversification of expressions towards air pollution activism throughout the last couple of years cannot be interpreted flatly as a middle class-urban struggle. As will be shown in the cases of citizen science and the popularisation of air quality science in China, the role of the internet (especially social media), the timing of actions (very short or short rather than long-term), and the actors (a synthesis of experts and engaged activists) makes the public engagement of air pollution a very difficult topic to frame.

Methodologically, the analysis results from the following activities: 1. A systematic review of national news outlets, activists’ websites, and Weibo (Twitter-like) accounts that provide information about air pollution events in the country between 2008 and 2013; 2. Interviews with scientific experts, citizens, start-ups, and NGOs that were part of the actions between 2012 and 2015.

The article is divided into three sections. The first presents a brief evolution of China’s environmental and air pollution management and the way environmental activism has been studied and problematized in the last decade. The second presents the background and context of air pollution activism and analyzes some cases of citizens, NGOs, start-ups, and scientists who became vocal about air quality between 2008 and 2015. The third discusses how to understand this period of change in public participation, resistance, and air quality governance.

From Ecological Modernisation to Environmental Activism

Environmental and Air Quality Management: An Official Context

During the last four decades, China’s sustained economic growth has produced unprecedented material wealth, lifting millions of people from poverty. However, this development has caused an overly complex environmental health crisis (Holdaway, 2010). China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2) (WRI, 2015), mostly as a result of its heavy reliance on fossil fuel consumption, of which coal represents about 70% (IEA, 2009).

Carter and Mol (2007) argued that during these decades, China has witnessed a process of ecological modernisation characterised by: 1. The transition from a socialist economy to a market economy and 2. Institutional and legal reforms to manage the environment. In the 1970s, as a newcomer to the United Nations (UN) stage, China ratified the declaration of the Stockholm Conference of 1972, which circumscribed environmental problems in the economic, knowledge-based, and management arenas (He et al., 2012). The declaration came at a key moment in the history of the country—that is, the verge of transitioning from socialist central planning to a socialist market economy, known as the ‘Chinese Economic Reform of 1978’ (hereinafter ‘Opening-Up’). Both the Stockholm Conference and the Opening-Up reforms shaped the basis of China’s environmental arena on the institutional, legal, and management fronts (He et al., 2012: 30).

Air pollution is one of the best-known facets of the complexity of environmental management in China. It dates back to the foundation of the country in 1949, with the effects of its reconstruction through a Soviet model known as ‘Big Push Industrialization’ (Naughton, 2007). This model produced the first ecological excesses of the triad of socialist planning, heavy industry, and land exploitation (Shapiro, 2001). During the ‘Great Leap Forward’ (1958-1960), the country witnessed the first peak of particulate pollution (PM) and sulphur dioxide (SO2), when ‘millions of so-called “backyard furnaces” flourished all over China in an ill-fated attempt to produce the much-needed steel for the nation’ (Fang et al., 2009: 80). Over the next four decades of intense industrial and economic development, boosted by the Opening-Up reforms, large areas of the country were clouded with air pollution, impacting health (Zhu et al., 2013), the environment, and the economy (Ho & Nielsen, 2013). China released a package of laws, plans, and policies to prevent and control air pollution through a top-bottom and command-and-control approach (Feng & Liao, 2016). In 2013, lacking effective results, China’s former premier, Li Keqiang, declared a ‘war’ against air pollution to comprehensively tackle the problem (Wong & Buckley, 2015). This unprecedented war will end in 2030, when China expects to attain the World Health Organization’s standards on air quality. The road to accomplishing this ambitious strategy remains slow and arduous. In 2014, only eight in seventy-four cities had attained national air quality standards (MEP, 2015).

In the process of ecological modernisation, the central government has presented civil society as a crucial actor for environmental governance, working in unknown fronts such as transparency, disclosure of information, and public participation (Jun, 2008; Zhang & Cao, 2015). In particular, sustainable development and wider legal rights (He et al., 2012) favoured the role of citizens and NGOs, after China’s 2001 inclusion in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the introduction of a series of domestic laws (i.e., the Cleaner Production and Promotion Law of 2003). These efforts, however, face enormous limits in terms of the exercise of critical citizenship and open access to environmental information (Mol, 2006; van Rooji, 2010; Wu, 2009). Studies show that decision-making is still shaped by extended practices of misreporting, faking data, and secrecy at local levels (Andrews, 2009; Ghanem & Zhang, 2014; IPE & NRDC, 2015). Restricted political space has shaped alternative ways citizens and non-traditional actors (e.g., academics, NGO, and enterprises) approach information about air quality data or influence public awareness.

Confronting Official Management: Environmental Pollution Activism

The literature about citizen participation and the environmental crisis in China has focused on the ways in which people have engaged in actions and demands to the government for effective governance. Two complementary concepts are proposed to understand this context. The first is ‘rightful resistance’ (Li & O’Brien, 2008), which explains how Chinese citizens framed their actions and language based upon the governmental boundaries and discourses to legitimise their demands. The second is ‘embedded activism’ (Ho & Edmonds, 2008), which presents a ‘respectful’ civil society that does not directly confront the government, thereby avoiding sensitive issues that could result in persecution.

Both rightful resistance and embedded activism face theoretical and practical problems. On the one hand, demonstrations and protests have proliferated across diverse geographical areas, actors, and methods, showing a spectrum of actions and diverse ways to navigate governmental opposition (Gardner, 2014; van Rooji, 2010). On the other hand, both concepts approach environmental activism from new middle class-urban settlers, within a strong presence of governmental institutions. Considerations about this population are important to evidence the new ecosystem of environmental resistance in cities like Beijing and Shanghai, which have strong law enforcement and central government pressure to control and regulate environmental pollution. Moreover, this group has been effective in permeating national and international media attention, diffusing Weibo messages, and establishing popular websites. Nonetheless, the situation might be different in the case of rural areas affected by pollution. Ethnographic works (Lora-Wainwright, 2013; Deng & Yang, 2013) demonstrate how rural settlers are confronting environmental pollution through resistance and citizen agency, but also with trade-offs with polluters. In this case, environmental activism does not follow the stereotype of environmental awareness coming after subsistence needs have been accomplished (Lora-Wainwright, 2013: 48), nor expecting that it will pressure policy measures, which is a common way to characterise new middle-class struggles. Paradoxically, in the case of rural environmental pollution, trade-offs between victims and polluting industries are very common, allowing polluters to co-exist and strategically blaming other issues that will not affect their economic interests, which is known as ‘piggybacking on other grievances’ (Lora-Wainwright, 2013: 248).

Van Rooji (2010) proposes the term ‘isolated activism’, which can be useful in finding answers to address the multiplicity of actions and contexts of environmental activism in China. The author analysed political and legal actions of pollution victims in China and found that this type of activism occurs so often that it has become a ‘developing form of social action’. More importantly, Van Rooji shows how differently each case is stated, negotiated, and solved in the eyes of victims and authorities. Precisely, the ‘not in my back yard’ (NIMBY) trend in environmental activism in China (Johnson, 2010; 2013) is articulated in Van Rooji’s analysis in the sense that citizens’ endeavours often conclude when problems affecting them individually are solved. NYMBYism shows those grey areas in which Chinese citizens understand and complain about specific environmental topics, often supported by NGOs, good relations with local officials, and scientific knowledge. NYMBYism, however, is limited in terms of reaching broader groups and supporting social causes, therefore these actions seldom transcend local matters, having few influence in city or national decision-making.

Making Air Pollution a Public Concern

This section analyses the background and context of China’s air pollution activism, analytically presenting some cases of citizens’ engagement with air pollution awareness in China. This stems from a systematic review of journalistic articles written between 2008 and 2013, and interviews with individuals engaged in air pollution activism. The systematic review was conducted using China´s Baidu search engine to seek articles in three official media outlets (Xinhua.net, People’s Daily, and China Daily), specifically articles containing keywords related to air pollution. All the articles were reviewed and codified according to the type of actors (i.e., official, NGO, scientific community, citizens), events (i.e., Olympics 2008, Airpocalypse 2013, US Twitter 2008-2010, regulatory and policy decisions), and initiatives (i.e., health campaigns, protection masks, discussion about indexes). Some pointed to the use of Weibo (China’s Twitter); therefore, there was a review of accounts involved in the specific event.

The interviewees were selected based on convenience and snowball samplings, due to the difficulty involved in reaching people who agree to talk about activism. The sampling considered individuals who either consider themselves to be environmental activists (based on their affiliation with environmental grassroots efforts or NGOs) or who have engaged and been covered by the media in activities intended to raise public awareness of air pollution over the period of time of the study, 2008 to 2015. In total, six semi-structured interviews are presented in this article, which has the approval of the interviewees. The interviews were conducted either through online call services or one-to-one, with a duration of approximately one hour. The cases analyzed here are mainly situated in the context of Beijing air pollution, providing different types of strategies, actors, and approaches to air pollution activism occurring in the city, though sometimes achieving national and international attention.

Beijing Olympics and the Popularisation of Air Quality Politics

In 2008, Beijing held the Olympics. The International Olympic Committee tasked the nation’s administration with working on air quality prior to and during the event (Ramzy, 2008). With the management of air pollution as a background, the Olympics triggered the legitimation of knowing and talking about air quality within different levels of society and at a national scale. The media played an important role in setting the tone of the agenda. Coverage about the topic increased (Kay et al., 2014) and was divided into two types of messages: (1) an explanatory approach about what was air pollution (‘popularising the topic’) and (2) a supportive approach toward the official strategies of preventing and controlling air pollution (‘legitimation of the topic’).

Before the Olympics, the government used to report in two ways through indices and criteria pollutant records used by experts and policymakers, and through public information in the form of blue-grey skies (blue for good air quality, grey for polluted) (Andrews, 2009). The official reports were published on some governmental websites, but with little accessible and relevant information for the public (Andrews, 2009). On 4 May 2008, three months before the Olympics, the official state media, Xinhua, released a report about air pollution. Among the people interviewed, Wang Qiang, professor and member of the China Meteorological Administration, explained, ‘The reason why Beijing’s five or six surrounding provinces are having a prevention plan (on air pollution) is because Beijing’s air pollution is not an exclusive problem, but a regional one. Air pollutants can travel from surrounding regions to Beijing’ (Xinhua, 2008). When talking about how China has reported fog (雾) as a weather condition, he said that it could have been misleading because, most of the time, the weather condition was actually haze (霾): ‘Fog (雾) and haze (霾) have ambiguous and complex relation, and we have been busy to not explain the public about it. The current weather report is shallow. It describes foggy days when in fact hazy days are the most common’ (Xinhua, 2008).

As the Olympics approached, international pressure on China increased (Hooker, 2008) and the official media closed ranks, echoing official measures and regulations. On 26 June 2008, the Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau (BEPB) sub-director stated, ‘According to the 14 stages of Beijing’s Air Pollution Plan, the 200 measures have been accomplished, together with the temporary emission reductions for the Games. I believe Beijing will attain the air quality standards during the Olympics’ (Xinhua, 2008b).

Indeed, the air quality during most of the Olympics attained Chinese standards (Rich et al., 2015). Radical measures, such as shutting down industrial facilities in the city and surrounding region and limiting the circulation of private cars (based on the ‘odd-even number’ on their plates), were key contributors to the temporal good air quality (Rich et al., 2015). Nonetheless, as soon as the Olympics ended, the air levels of pollution returned to their historical levels (Spencer, 2008).

The US Embassy Incident

Efforts made to host a Blue Skies sporting event were not traduced in the public trust to official air quality monitoring and data. Soon after the end of the Olympics, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing started posting a real-time Air Quality Index (AQI) on its Twitter account; this was widely viewed and shared by Chinese netizens (Kay et al., 2014). AQI is a communicative tool to provide information, in a simple way, about the air pollution levels of common criteria pollutants, such as ozone (O3), particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), and sulfur dioxide (SO2). AQI is expressed as a single number that indicates the concentration of pollutants, ranging from 0 (good air quality) to 500 (hazardous). ‘The higher the index, the higher the level of pollutants and the greater the likelihood of health effects’ (Griffin, 2007: 312). According to the U.S. Embassy, its AQI had the intention of informing US citizens living in Beijing to take the necessary actions to protect their health.

The notoriety of the U.S. Embassy’s AQI did not go unnoticed by Chinese officials. According to a leaked cable from WikiLeaks (U.S. State Department, 2009), China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs presented complaints to the U.S. Embassy, based on reports from the BEPB and the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). They argued that the U.S. data, which stemmed from a particulate monitor placed on the compound of the Embassy, was producing ‘“confusion” and undesirable “social consequences” among the Chinese public’ (U.S. State Department, 2009).

Beijing and the U.S. Embassy had different methods of obtaining, analysing, and publishing air quality data. AQI readings published by the U.S. resulted from a single machine, a MetOne BAM 1020, placed in the busy traffic district of Chaoyang. The AQI ‘real-time’ data was an hourly updated aggregate index. It included a criteria pollutant known as fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), a particle with an aerodynamic diameter smaller than 2.5 μm (approximately 1/30th the average width of a human hair), which can lodge deeply into the lungs. Beijing’s counterpart used an aggregate Air Pollution Index (API) from multiple monitoring stations located around the city. The API delivered a report every 24 hours and did not include PM2.5, but only coarse particulate matter (PM10)—that the AQI had as well—which does not pose as much health risk as fine particulate matter.

The US Embassy incident put on the table the continuities between the political and technoscientific, in which the indexes project a ‘specific form of power’ (Jasanoff, 2004). Accordingly, the US AQI and China’s API represented two different forms of air pollution governance—the former focusing on citizen’s health and the latter addressing policy issues. Although air quality indexes were created for these and other potential uses, it is critical when they mislead public awareness and policy issues (Ruggieri & Plaia, 2012). In that regard, there are examples around the world that portray the low effectiveness of these types of indexes in terms of achieving the purposes for which they were created (Hsu et al., 2012). The discussion opened by Chinese netizens and activists pointed to the disparities between the readings of AQI and API, resulting in the different approaches to open access information and health effects. Their intuition was that China’s API showed criteria pollutants that were not as harmful as PM2.5, in order to demonstrate annually decreasing concentrations in PM10 and SO2 (Ho & Nielsen, 2013), and to avoid directing public attention to the magnitude of daily exposure to PM2.5.

Photography record and social commentary

The popularisation of the air quality topic triggered the first citizen actions expressing better information and doubts about official data. In 2009, Weibo, a website similar to Twitter, was launched and became one of the preferred channels of social commentary. Netizens made air pollution a common topic of environmental and political criticism (Kay et al., 2014) by posting snapshots of hazy skies and questioning air quality management.

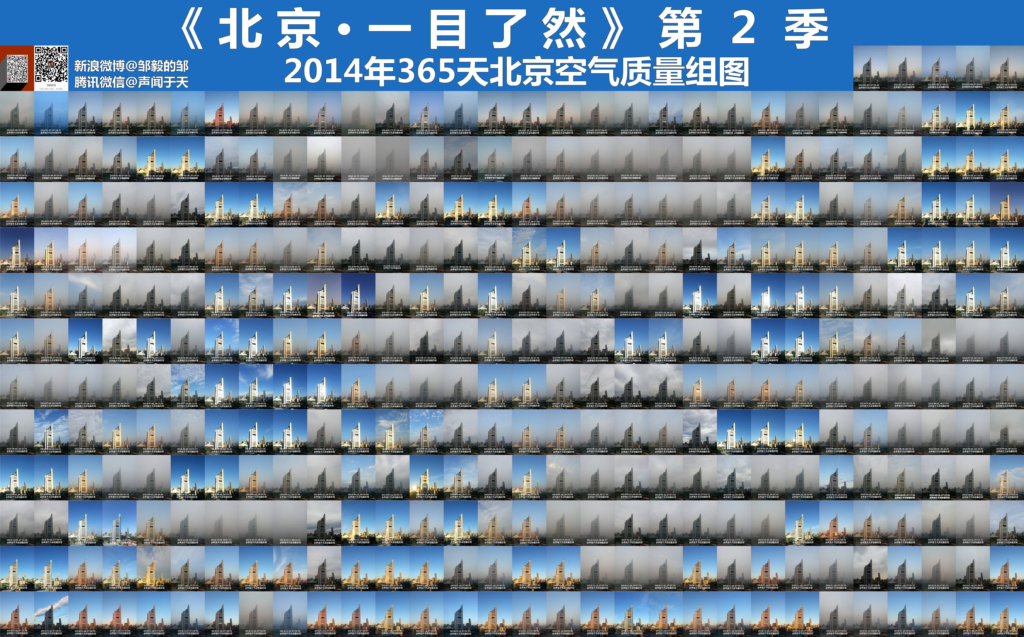

One of the Weibo activities that received the most media attention was the photographic record created by Beijing resident Zou Yi in 2013 and 2014 (China Daily, 2015). After two years, he organized an exposition called ‘As plain as daylight’ (from the Chinese idiom 一目了然), displaying daily photos of the Beijing sky taken from the same place (see Figure 1). The exposition gained national exposure when it was mentioned in the documentary ‘Under the Dome’ (2015) by Chinese journalist Chai Jing, which was seen 200 million times in the course of a week (Ren, 2015).

Photography and social commentary have been continuous forms of public engagement regarding air pollution to the present day. They were key, for instance, to one of the worst episodes of air pollution in Beijing—the ‘Airpocalypse’ of January 2013 (Kaiman, 2013), which became a political and public issue. Beijing real estate tycoon Pan Shiyi openly asked his seven million Weibo followers if China ‘should employ a stricter air-quality standard’, while Shi Yigong, professor at Tsinghua University, posted in his popular blog that air pollution was ‘the most upsetting and painful thing’ about life in China (LaFraniere, 2012).

Photographs and online social commentary, in the context of Chinese air pollution events, should be understood as a civic record without the purpose of becoming a research tool (Dickinson et al., 2010; Silvertown, 2009). However, the double approach of registering and filling the gap of information cannot be considered outside the diffusion of technoscientific knowledge. Photos served at times as legitimate counter-facts to air pollution data for audiences that did not have access to, or did not understand, the index data. The subtle critique of a photograph, however, was hard for the government to control. Applying censorship would have led to exaggeration, thus casting more doubt on official data.

With less censorship of air pollution posts, Weibo’s trending terms related to the environment included air quality data, pollutants, real-time index, respiratory diseases, and heart effects, among others (Kay et al., 2014). The civic record of air pollution became a public platform for the popular understanding of air quality. The photographs made it accessible to a larger audience.

Nevertheless, it is clear that this phenomenon has some limits. The government has increasingly adopted a communication strategy on Weibo, asking officials in the environmental sector to actively post about air quality on the social network. Businesses have done the same, posting about air quality products, beauty, health protection, etc. Together, official and corporate social media activity is the main source of China’s current Weibo activity regarding air pollution (Kay et al., 2014).

Grassroots Testing and Monitoring

In the context of the U.S. Embassy incident and the Airpocalypse, some citizens and NGOs engaged in air pollution awareness through diverse actions, such as using air quality testing machines, informing the public about the scientific evidence, and discussing the effectiveness of masks and air purifiers.

In November 2011, the Beijing-based NGO Green Beagle (GB) organised and coordinated a national action to independently monitor air pollution. The action was called ‘My country measures the air’ (in Chinese, 我为祖国测空气) and attracted national media attention (Feng & Lu, 2011; Xinhua, 2011). Although the action was directly addressed to its network of volunteers and partners, GB sent a general message about the scarce information on PM2.5 and the need for more open information for the public.

GB had prior experience only with testing radiation using low-cost devices. Its focus on air pollution occurred in May 2011. Some months before the national action, GB started using portable, low-cost particle counters to familiarize itself with measuring particulates. Some of its members, with post-graduate degrees in environmental sciences, asked their academic and professional networks about the type of data resulting from these devices. They learned that although portable particle counters provided a rapid solution, they were not very reliable sources of air quality data. GB investigated accepted standards by expert communities. When the national action began, GB asked five cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Wenzhou, and Wuhan) to commit to acquiring a similar air quality device.

According to Xiaoxia He (2015), director of GB, it has been a process of learning-in-the-making. Purchasing the instruments, organising the national initiative, and publishing the data were all challenging because of the technical (i.e., calibrating the test equipment) and scientific demands (including control measures of temperature, humidity, pressure, etc.). The political side of the action was clearly the most difficult aspect to manage. In that regard, after the national call was launched, GB carefully changed the description of what it was doing. The government would have banned statements that GB was producing alternative air quality data. Instead, ‘testing’ the air quality was acceptable because the resulting data would be used for internal purposes and records only. GB publicly acknowledged there was no ‘comparability’ between the official API and its data, which had only the purpose of ‘judgement’ and ‘reference’ (she uses the Chinese words ‘判断和参考’). About the change of strategy, Xiaoxia justifies it in the context of low public trust in air quality data and scarce public awareness of health effects. GB understood that ‘civic testing’ (in Chinese, ‘民间检测’) was an exercise that could help people understand why China had to update the country’s standards as well as bring clarity to the relationship between pollution and health.

GB’s network of volunteers shows another side of the citizen engagement with air quality in China. One of the most active is Liu Jun, a young man who lives in the city of Wuhan, located in the centre of the country. Since 2012, Liu has divided his time between working in the financial area of a company and testing air pollution from his apartment. He convinced a few volunteers (among them, local school teachers and a café owner) to use a device and deliver city online reports on Weibo. Once they agreed to participate, they called themselves ‘Wuhan Air Watch Organisation’ (Air Watch) and began reporting online ‘Wuhan’s Air Diaries’ (in Chinese, 武汉空气日记), with information about their daily tests.

Air Watch has interacted with local environmental officials and experts to receive more advice and legitimise its method of collecting data. Liu (2015) explained that, in one instance, he contacted the dean of the School of Environment at Wuhan University of Geosciences to ask for his opinion. The professor was surprised by Liu’s initiative and confirmed that Air Watch was using standardised methods. However, he also recommended exercising more caution about sending the wrong message to citizens. For example, Liu learned that the values of AQIs and APIs were different from their particle counter values. Moreover, a more systematic approach to Air Watch’s own information could help people understand its reports.

Therefore, in 2013, Air Watch launched software containing historical readings of the updated official AQI (before API) and its own test readings. The official AQI was not available to the public, so Air Watch provided another form of information. Led by Liu, volunteers in 10 cities are recording air pollution and sending the data through mobile devices. The software transforms this data into reports that are released online via Weibo, together with atmospheric and weather data (e.g., pressure, humidity, and temperature), photos of the skies, and the AQIs from the U.S. Embassy and the local Environmental Protection Bureaus. According to Liu, this range of information and the records of both official and non-governmental data constitute a more scientific approach to the subject.

The Beijing-based NGO Friends of Nature (FON) was another key actor that joined the process initiated by GB and Liu. FON is the oldest environmental NGO in China. In 2014, FON began ‘The Blue Skies Lab’ (in Chinese, 蓝天实验室, hereinafter ‘Blue Skies’), a series of workshops and field trips addressed to citizens interested in understanding air pollution. According to Blue Skies coordinator Hui Guo (2015), FON did not want to measure air quality using an expensive device; instead, it wanted to use portable particulate counters in places like public transportation (e.g., the subway system and buses), residential spaces, and commercial spaces (e.g., malls, indoor playgrounds, etc.). Guo argues that although there are technical reasons and limitations, like controlling the test site condition (e.g., humidity, pressure, and levels of radiation), FON wants to make people aware of the presence of air pollution in their daily spaces. People who join Blue Skies often interact with academics and experts who attend the activities to understand the science behind air quality and sensors. Blue Skies has organised field trips to BEPB to talk with officials about the city’s plans and air quality indices.

In general, the process and related actions of GB and ‘My country measures the air’ depict another side of citizen engagement with air quality, through the use of more traditional means of citizen science. The door left semi-open space for public participation related to air pollution (Huang, 2014), enabled by the strategic use of instruments to provoke local awareness. Individuals in second-tier cities (i.e., Wuhan) have echoed the transboundary effect of air pollution and the popularisation of the topic. The adoption of technological devices in different geographical and quotidian spaces pretended to challenge the official air pollution data. Unlike social commentary and the photographic record, the national call was purposely intended to produce an alternative approach to the existent data. This required a more complex understanding of air pollution and technical instruments. The networks of academic experts and local environmental officials were key to legitimising their instruments and methods, bridging communication with wider audiences, and sometimes maintaining good relations with officials.

In 2012, earlier than planned, China updated its API to an AQI, adding PM2.5 and health advice very similar to the index of the U.S. Embassy. It is interesting to see the strategies that members of the action have adopted. GB and FON, strategically entrenched in their role of ‘civic testers’, did not controvert official data but, instead, focused on education and awareness. This change can be framed through the embedded activism and rightful resistance approach: GB and FON formalised their role in the public understanding of air pollution by adopting the rhetoric of the limits imposed by the government and softened the scope of their data. On the other hand, Air Watch has advanced in refining data and expanding its approach to other cities—perhaps because they are less visible to local powers. The actors involved in ‘My country measures the air’ are what can be called ‘naive experts’ who introduce the use of technological instruments to raise air pollution awareness. As their action evolves, they adapt their discourse to the existent limits of the political and knowledge contexts.

The Unexpected Actor: Expat Community

Air pollution in China and citizen participation is a topic unexplored in the literature but one that might contribute to different ways of thinking about the dynamism of activism in the country. Foreign citizens also must explore ways to influence citizen participation and awareness in regard to air quality. This phenomenon is not so new in the wider context of environmental activism. Since the 1990s, the country has witnessed a growing number of transnational networks of NGOs and civil society communities interacting with Chinese citizens (Chen, 2010).

The health blog of Dr. Richard Saint Cyr, My Health Beijing, is one example of how air pollution in China opened the door of the expat community. Dr. Saint Cyr is a family medicine doctor from the U.S. who settled in Beijing in 2006. He works for the elite Beijing United Family Hospital, which provides bilingual (Chinese-English) services to patients. After coming to China and realising that patients lacked reliable information about pollution and health risks, he launched his blog mainly to address the expat community and Chinese citizens who read English.

One topic about which he blogged was his worries about air pollution in Beijing. He believed the pollution was very significant, although he could not find any specific data or historical records. Before the Beijing Olympics, he posted information about how to protect oneself from air pollution and why the problem was a health threat. He acknowledged his limitation in reaching wider audiences: ‘It did frustrate me at the beginning realizing that my blog readers were getting health advice but most Chinese people did not had a clue’ (2015).

After the Olympics, and with the release of AQI by the U.S. Embassy, Dr. Saint Cyr noticed that the Chinese patients were asking more questions about the topic, such as which masks were more effective, which air purifier worked better, what to eat, and how to protect their children. In 2009, he posted:

In real life terms, there is definitely a risk from air pollution to your health. The underlying damage seems to be the tiny particles getting sucked deep into your lungs and initiating an inflammatory response—and long term exposure has a dose-response increase in chronic bronchitis, lung cancers, and atherosclerotic heart disease. It has been studied extensively, and I have links below to a couple of the best articles.

(Saint Cyr, 2009)

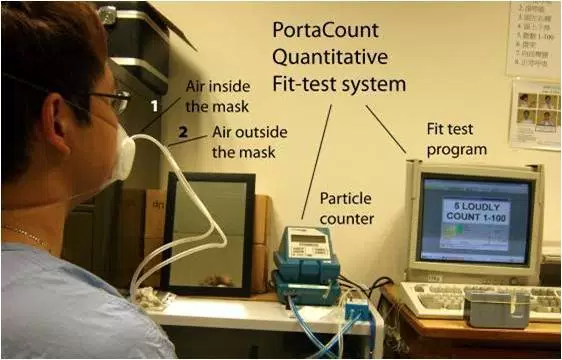

After studying Mandarin, Dr. Saint Cyr decided to deliver bilingual information on Weibo. His posts about air pollution interested his followers, most of whom were Chinese. He decided to publish two types of information about air pollution: an explanation of relevant peer-reviewed studies and the results of tests of particulate respirators (masks that provide protection from air pollution) and air purifiers (see Figure 3).

The response to this information has been positive. Today, Dr. Saint Cyr has 36,000 followers. He explains, ‘Chinese people are starved for trustworthy health information about everything. So if I could provide evidence based tips I really feel like I contributed a little bit to some people in China’ (2015).

Project FLOAT, led by Xiaowei Wang, is another example of the civic engagement of air pollution by foreigners. In 2012, Wang, an American and Harvard master’s degree student, came to China to develop a project focusing on pollution awareness through citizen science and design. Along with two friends, Wang approached kite masters in Beijing and proposed installing, on their kites, do-it-yourself (DIY) sensors to measure air pollution.

FLOAT tried to take off through community participation. As Xiaowei explains, ‘If you go into the Hutongs (historical residential areas) to the community centres, there is information and knowledge sharing and people take care of the environment together, in a non-official way’ (2015). The project made an online call for volunteers and participants. For three weeks, participants participated in workshops as well as learned how to make a kite and install air quality sensors. Arduinos, an open-source hardware and software platform very common in these types of DIY projects, was used to measure air quality.

In the air, the sensors displayed colours with LED lights: green indicating good air quality and pink indicating very poor air quality. Xiaowei maintains the resulting information was not intended to produce insight like the official or U.S. Embassy indices. Combining DIY electronics with community participation in public areas was an invitation to engage citizens in the understanding of air pollution in a more quotidian way. ‘An important part of citizen science is not just collecting data right? Because you could have this network of machines collecting data for you. But a large part of it is social, and cultural, and having citizens informed each other and engaged each other. That way, any kind of dry science becomes really meaningful’ (2015).

Another area in which expats interacted with Chinese citizens was the creation of start-ups with a social message behind the business. Two examples portray this context: air purifiers and wearable devices.

Thomas Talhelm, a U.S. psychologist who had lived in China since 2006, created the start-up Smart Air. It started operating in 2013 by selling air filters and DIY air purifiers. Earlier that year, after witnessing the ‘Airpocalypse’ in Beijing, Talhelm was thinking not about opening a business but, rather, about how to protect oneself from air pollution. He checked the prices of most of the air purifiers on the market—they ranged from 1,000 yuan to 8,000 yuan (about $180 US to $1,300 US). By conducting a simple search on the internet, Talhelm learned that it was relatively easy to build an air purifier—just assemble a fan and a filter (2015).

From Chinese websites, Talhelm purchased several filters that claimed to follow the standard of the U.S. Department of Energy (known as ‘high-efficiency particulate arrestance’ (HEPA)). Then he bought a $200 US indoor particle counter to confirm the filters’ efficiency. Eventually, some friends who had branded air purifiers in their homes let him conduct the same tests. He organised the data and published it online. The demand for trustworthy information about air filters was increasing in China, as were the prices of the air purifiers. Therefore, Talhelm asked some friends (i.e., expats and Chinese) to open the start-up and sell the filters and fans on the popular e-commerce website, Taobao. Since then, they have also run workshops in different cities in China for the price of the kit (i.e., filter and fan). In those workshops, they introduce the data, how Talhelm measured it in his room, and how it should be used. Although new companies have tried to replicate the approach of Smart Air, Talhelm thinks that customers recognise that behind their filters is a level of independence and engagement that is hard to find in local competitors.

An area that has received considerable attention from DIYers and citizen science projects in the last few years is portable and wearable sensors. In the U.S., projects like Habitat Map (aircasting.com) show the potential of this next generation of personal devices and crowdsourced maps. In China, they are relatively new. Han Wang [1] (2015), a young entrepreneur and bachelor’s degree student at a renowned U.S. university, saw the possibility of introducing wearables that could measure PM2.5 in China. At this time, the device did not exist; therefore, a group of classmates created a prototype. The university encouraged them to commercialise it, so they began a journey that has taken Wang back to China.

Although the device has not been released commercially, it has made a path in the media and received support from the popular hardware developer, Hax. Wang has mixed feelings about its potential use in China. He regards the political culture as not ready to allow millions of potential users of wearables to sense air pollution. He believes that, because of the magnitude of the problem, Chinese citizens have the right to know what is really happening at the street level. He concludes that sensors will be the main challenge for the government in the near future.

Discussion: Bridging Air Pollution Activism for a New Governance Era

This article intended to echo recent debates from STS and Chinese Studies about citizen agency and environmental health in China by discussing examples of citizen science and the popularisation of technoscientific knowledge about air pollution. In the changing landscape of environmental governance in China, three aspects have cleared the way for citizens to become more aware and effective in demanding environmental protection: 1. The role of the internet in diversifying the circulating messages and sources, not always respecting the official or sound technoscientific knowledge but also generating alternative ‘disorganised knowledge’ (Bertilsson, 2002); 2. The government’s relatively open attitude towards public engagement that is creating new ‘safe spaces’ or ‘blind spaces’ for citizen participation; 3. The political pressure and media attention brought about by international events (the Olympics) and pollution events (i.e., the U.S. Embassy incident and Airpocalypse).

This new scenario is helping to overcome what Mol (2009) understood as an ‘information-poor’ environment: information asymmetries and the suppression of alternative informational sources. Between 2008 and 2013, it appears that China had a more robust and diverse information context, in part because of citizen participation and the adoption of sound technoscientific knowledge. However, there is a long way to go to overcome the pushback that the government displays against this type of participation. The cases presented in this article portray unsettled issues: citizens demanding more transparent and reliable information, and a government that prioritises political control, thereby centralising knowledge management.

The novelty of citizen science and the popularisation of scientific knowledge about air pollution in China help create an understanding of the complexity of Chinese citizen participation in the last decade. In general, the examples above show how citizens adopted a ‘civic’ (Corburn, 2005; Fortun & Fortun, 2005; Wylie et al., 2014) approach towards technologies (i.e., testing instruments and monitoring devices) and science (especially epidemiological studies). By choosing the ‘correct’ technologies and sound science, activists were willing to question what they interpreted as a main problem in China—trustworthy information.

This context was far from static (see Figure 4). From 2008 to 2011, citizens expressed distrust of official data. The motivations behind the related actions were to confront the existing knowledge and provide more reasons (such as health effects) for citizens to demand prompt measures. Reframing a problem that was traditionally in the hands of the government and experts gave citizens a platform on which to interact with them and make own ignored issues clear (i.e., PM2.5 and health effects). Ottinger (2010b) referred to this type of situation as a change in the epistemic reference of experts and the public. After 2012, mistrust has vanished to differing degrees, and confronting data is no longer so important. The redirection included testing instead of monitoring, data for reference instead of comparability, and assessment of commercial products (e.g., masks, air purifiers) instead of the effectiveness of official decisions.

In that sense, China’s activists (including expats living in China) differ from their Western counterparts in how they express their political struggle. Their success always remains an open question. Kullenberg (2015) explained it this way: Producing facts outside the institution of science and the government is an important achievement but not the most relevant one. In the context of limited rights participation, it was important to legitimise activists’ actions in the eyes of possible censorship. Survival of the practice became key to understanding their role and, more importantly, to being conscious of the possibilities that technoscientific knowledge offered for participation.

Whether this is a ‘tactical’ (Wylie et al., 2014) or ‘normal’ evolution of their actions is something that the activists do not express straightforwardly. In some cases, they explain that the weight of technoscientific knowledge softened the scope of their actions. When asked about using any strategy to avoid official censorship, they all recognised that they were conscious that their activity could become a sensitive issue for authorities; therefore, they tried to be as unconfrontational as possible. They also expressed that either they were lucky or their audiences were not significant enough for them to be considered a problem. Only Wang affirmed that this has been an important issue for the start-up—so much so that they preferred to present themselves as a business idea.

Another noteworthy point is the obstacles for obtaining reliable data. After consulting with their networks, which included experts and environmental protection officials, NGOs have found that their data is limited. Expats tried to legitimise their knowledge with sources they believed were out of the circuit of Chinese people and that were accepted by international scholars. The cases of photographic record and the commercialisation of purifiers and wearables are problematic in the sense that they do not bridge resistance and citizen science flatly. It is important to ask whether these constitute channels of citizen science or whether they can be considered citizen science. They can be regarded as so, but only in the context of ‘poor-information’, where ‘naive experts’ use them for a higher (but not public) purpose (e.g., criticize official data, support citizens’ agency, etc.).

In general, more research is needed to understand if these types of resistance are replicable for other pollution events and ecological struggles. Deng & Yang (2013) support the idea that in China, ‘pollution and protest is context dependent’ (2013: 323). However, from the perspective that citizen science is a form of resistance, air pollution activism evolved from specific social (i.e. urban, middle educated classes) and political contexts (i.e. Beijing Olympics, US Embassy incident, and Airpocalypse) into a wide range of actions that had different angles on the internet, second-tier cities, and business world. In this way, messages and actions to approach air pollution were distinctive and depended on the public, the communities of activists and the type of knowledge (i.e. health, monitoring technology, regulation).

The context and the cases presented here portray an extended form of governance of the atmosphere and society (Whitehead, 2009). However, two complex questions remain: 1. Has the government taken back control of citizen participation, at least from the side of the citizen science approach? and 2. What is the role of the next generation of citizen engagement with air pollution? For the first question, paradoxically, there is reason to think that the government has returned trust. At least individuals and organisations interviewed think that official information is more reliable and that ‘things have changed’. However, they consider that air quality activism was key in achieving positive changes, but now is the time for other actions, such as indoor pollution or wearable devices. This space for new actions allow for two types of speculation. The first, popularisation of wearables might bring again a crisis in the current regime of air quality data. This knowledge could constitute a ‘peer review’ (Yearley, 2006) for policy purposes and a new area of citizen action. Second, until now, we have witnessed only the beginning of citizen engagement with air quality in China. A possible direction is that cheap monitoring and testing devices could become more accessible to people living in second-tier cities and villages, which will open new patterns of activism, contextualized practices of participation and governmental control. With the rhetoric of air quality and health effects becoming ordinary, it seems that localised resistance through citizen science will pose greater challenges for environmental authorities that pretend to use centralized data analysis and unified information platforms.

End notes

[1] This name was changed at the interviewee’s request.

References

Andrews SQ (2009) Seeing through the smog: understanding the limits of Chinese air pollution reporting. China Environment Series, 10 5-29. Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/andrews_feature_ces10.pdf

Bertilsson TM (2002) Disorganized Knowledge or New Forms of Governance. Science Studies 15(2): 3-16.

Carter NT & Mol APJ (2007) China Environmental Governance in Transition. In: Carter NT & Mol APJ (eds) Environmental Governance in China. London and New York: Routledge, 1-22.

Corburn J (2005) Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

China Daily (2015) Huanbao daren lianpai 365 tian “yimuliaoran” jilu Beijing tianqi 环保达人连拍365天“一目了然”记录北京天气. 4 January. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/interface/zaker/1142841/2015-1-4/cd_19233571.html (accessed 12.10.2015).

Deng Y & Yang GB (2013) Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context. The China Quarterly 214: 321-336.

Dickinson JL et al. (2010) Citizen Science as an Ecological Research Tool: Challenges and Benefits. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 41: 149-172.

Fang M et al. (2009) Managing Air Quality in a Rapidly Developing Nation: China. Atmospheric Environment 43: 79–86.

Feng J & Lu Z (2011) Wo wei zu guo ce kongqi 我为祖国测空气. Available at: http://www.infzm.com/content/64281 (accessed: 15.10.2015).

Feng L & Liao WJ (2015) Legislation, Plans, and Policies For Prevention and Control of Air Pollution in China: Achievements, Challenges, and Improvements. Journal of Cleaner Production 112: 1-10.

Fortun K, Fortun M. 2005. Scientific Imaginaries and Ethical Plateaus in Contemporary U.S. Toxicology. American Anthropologist, 107(1): 43-54.

Gardner D (2014) China’s environmental awakening. The New York Times, 14 September. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/15/opinion/chinas-environmental-awakening.html?_r=0 (accessed 12.10.2015).

Ghanem D & Zhang J (2014) ‘Effortless Perfection:’ do Chinese Cities Manipulate Air Pollution Data?Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 68(2): 203–225.

Griffin R (2007) Air Quality Management (second edition). Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis.

Guo H (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (20.7.2015).

He G et al. (2012). Changes and Challenges: China’s Environmental Management in Transition. Environmental Development 3: 25-38.

He X (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (17.5.2015).

Ho M & Nielsen C (2013) Air Pollution and Health in China: an Introduction and Review. In: Ho M & Nielsen C (eds) Clearer Skies Over China. Reconciling Air Quality, Climate, and Economic Goals. London, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 3-58.

Ho P & Edmonds RL (eds) (2008) China’s Embedded Activism: Opportunities and Constraints of a Social Movement. London: Routledge.

Holdaway J (2010) Environment and Health in China: an Introduction to an Emerging Research Field. Journal of Contemporary China 19(63): 1-22.

Hooker J (2008) Beijing Announces Traffic Plan for Olympics. New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/21/world/asia/21china.html (accessed 12.4.2013)

Hsu A et al. (2012) Seeking Truth from Facts: The Challenge of Environmental Indicator Development in China. Environmental Development 3: 39-51.

Huang G (2014) PM2.5 Opened a Door to Public Participation Addressing Environmental Challenges in China. Environmental Pollution 197: 1-3.

Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs (IPE) & Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) (2015) New Mindsets, Innovative Solutions. 2014-2015 Annual PITI Assessment. Available at: https://www.nrdc.org/resources/new-mindsets-innovative-solutions-2014-2015-annual-piti-assessment (accessed 15.10.2015).

International Energy Agency (IEA) (2009) Cleaner Coal in China. Paris: OECD/IEA. Available at: https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/coal_china2009.pdf (accessed 15.10.2015)

Jalbert, K (2016) Building Knowledge Infrastructures for Empowerment: A Study of Grassroots Water Monitoring Networks in the Marcellus Shale. Science & Technology Studies 29(2): 26-43.

Jasanoff S (2004) States of Knowledge. The Co-production of Science and Social Order. London and New York: Routledge.

Jasanoff, S., & M. L. Martello. (2004). Earthly Politics: Local and Global in Environmental Governance. MIT Press.

Johnson T (2010) Environmentalism and NIMBYism in China: Promoting a Rules-based Approach to Public Participation. Environmental Politics 19(3): 430-448.

Johnson T (2013) The Health Factor in Anti-Waste Incinerator Campaigns in Beijing and Guangzhou. The China Quarterly 214: 356-375.

Jun M (2008) Your right to know: a historic moment. China Dialogue. Available at: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/1962-Your-right-to-know-a-historic-moment (accessed 12.10.2015).

Kaiman J (2013) Chinese Struggle through ‘Airpocalypse’ Smog. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/16/chinese-struggle-through-airpocalypse-smog (accessed 12.4.2013)

Kay S et al (2014) Can Social Media Clear the Air? A Case Study of the Air Pollution Problem in Chinese Cities. The Professional Geographer 67(3): 351-63.

Kullenberg C (2015) Citizen Science as Resistance: Crossing the Boundary Between Reference and Representation. Journal of Resistance Studies 1(1): 50–76.

LaFraniere, S. 2012. Activists Crack China’s Wall of Denial About Air Pollution. Jan. 27. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/28/world/asia/internet-criticism-pushes-china-to-act-on-air-pollution.html

Li LJ & O’Brien K (2008) Special Section on Rural Protests. The China Quarterly 193: 1–139.

Lin X & Elder M (2014) Major Developments in China’s National Air Pollution Policies in the Early 12th Five‐Year Plan (No. 2013-02). Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Available at: http://pub.iges.or.jp/modules/envirolib/view.php?docid=4954

Liu J (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (11.7.2015).

Lora-Wainwright A (2013) Dying for Development: Pollution, Illness and the Limits of Citizens’ Agency in China. The China Quarterly 214: 243-254.

Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP-China) (2015) MEP releases air quality status of key regions and 74 cities in 2014. 2 February. Available at: http://english.mep.gov.cn/News_service/news_release/201502/t20150209_295638.htm(accessed 13.10.2015).

Mol APJ (2006) Environment and Modernity in Transitional China: Frontiers of Ecological

Modernization. Development and Change 37(1): 29–56.

Mol APJ (2009) Environmental Governance through Information: China and Vietnam. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 30: 114–129.

Naughton B (2007) The Chinese Economy. Transitions and Growth. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Ottinger G (2010a) Buckets of Resistance: Standards and the Effectiveness of Citizen Science. Science Technology and Human Values 35: 244–270.

Ottinger G (2010b) Epistemic Fencelines: Air Monitoring Instruments and Expert–Resident Boundaries. Spontaneous Generations: A Journal for the History and Philosophy of Science 3(1): 55–67.

Ramzy A (2008) Beijing’s Olympic War on Smog. TIME. 15 April. Available at: http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1730918,00.html (accessed 14.10.2015).

Ren, Y (2015) Under the Dome: Will this Film be China’s Environmental Awakening? The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/mar/05/under-the-dome-china-pollution-chai-jing (accessed 2.4.2015)

Rich D et al. (2015) Differences in Birth Weight Associates with the 2008 Beijing Olympics Air Pollution Reduction: Results from a Natural Experiment. Environmental Health Perspectives 123(9): 880-887.

Ruggieri M & Plaia A (2012) An Aggregate AQI: Comparing Different Standardizations and Introducing a Variability Index. Science of the Total Environment 420: 263-272.

Saint Cyr (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (30.9.2015).

Silvertown, J (2009) A New Dawn for Citizen Science. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24(9): 467–71.

Shapiro J (2001) Mao’s War Against Nature. Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spencer R (2008) Beijing Smog Returns after Olympics. The Telegraph. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/3043321/Beijing-smog-returns-after-Olympics.html (accessed 12.4.2013)

Talhelm T (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (06.01.2015).

U.S. State Department (2009) Embassy air quality tweets said to “confuse” Chinese public (Diplomatic cable). 10 July. Available at: https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09BEIJING1945_a.html (accessed 12.10.2015).

van Rooij B (2010) The People vs. Pollution: Understanding Citizen Action Against Pollution in China. Journal of Contemporary China 19 (63): 55–77.

Wang H (2015) Interviewed by: Rodolfo Hernández-Pérez (13.5.2015).

Whitehead M (2009) State, Science and the Skies: Governmentalities of the British Atmosphere. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wong E & Buckley C (2015) Chinese Premier Vows Tougher Regulation on Air Pollution. New York Times. 15 March. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/16/world/asia/chinese-premier-li-keqiang-vows-tougher-regulation-on-air-pollution.html?_r=0 (accessed 14.10.2015).

World Resources Institute (2015) The History of Carbon Dioxide Emissions. http://www.wri.org//blog/2014/05/history-carbon-dioxide-emissions (accessed 26.10.2015).

Wu, F. 2009. Environmental Politics in China: An Issue Area in Review. Journal of Chinese Political Science 14:383–406

Wylie J et al. (2014) Institutions for Civic Technoscience: How Critical Making is Transforming Environmental Research. The Information Society 30(2): 116-126.

Xinhua (2008) Guanzhou diqu wuri de changqi bianhua qushi 广州地区霾日的长期变化趋势. 3 April. Available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/environment/2008-04/03/content_7912357.htm (accessed 29.07.2009).

Xinhua (2008b) Beijing shi huanbaoju: aoyunhui kongqi zhiliang dabiao you baozhang.北京市环保局:奥运会空气质量达标有保障. 24 June. Available at: http://www.bj.xinhuanet.com/bjpd_2008/2008-06/24/content_13629115.htm (accessed 29.7.2015).

Xinhua (2011) “Woweizuguocekongqi” – zhongguogongzhonghuanjinghuanbaoyishijinru “lizishidai” “我为祖国测空气”——中国公众环保意识进入“粒子时代”. Available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/society/2011-12/02/c_111212131.htm (accessed: 15.10.2015).

Yearley S (2006) Bridging the Science-Policy Divide in Urban Air-Quality Management: Evaluating Ways to Make Models More Robust Through Public Engagement. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 24: 701–714.

Yearley, S., S., Cinderby, J., Forrester, P., Bailey, & P. Rosen. (2003). “Participatory Modelling and the Local Governance of the Politics of UK Air Pollution: A Three-City Case Study.” Environmental Values 12 (2): 247–62.

Zhang, B & Cao C (2015) Policy: Four gaps in China’s New Environmental Law. Nature 517: 433–434. Available at:http://www.nature.com/news/policy-four-gaps-in-china-s-new-environmental-law-1.16736

Zhao LJ et al. (2015) How China’s new air law aims to curb pollution. China Dialogue. 30.12.2015. Available at: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/8512-How-China-s-new-air-law-aims-to-curb-pollution (accessed 3.20.2016).

Zhu C et al. (2013) China Tackles the Health Effects of Air Pollution. The Lancet 382(9909): 1959–1960.