Keywords:

civic tech; decentralization; open source; place-based; democracy; political action; municipalism; radical; collaborative; participatory; Madrid

by Syed Omer Husain*, Alex Franklin**, Dirk Roep***

* Rural Sociology Group, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands;

** Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Coventry University, Coventry, England;

*** Rural Sociology Group, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands

Introduction

Over the past few decades, governments have initiated hundreds of digital democracy experiments under the umbrella of what is called civic tech: digital tools for civic engagement and participation. These experiments are in part a response to claims of democratic deficit (Bekkers, Dijkstra & Fenger, 2007), collapsing trust in national governments (Friedman, 2016) and civic disengagement (Wike et al., 2016). Technology that enables citizen engagement and participation has captured a lot of attention and is referred to with many different terms. E-democracy (Chadwick, 2003), e-government (Layne & Lee, 2001), open government (Attard et al., 2015), crowdsourcing democracy (Bani, 2012), Govtech (Adler, Fischer & McFarlane, 2017), smart government and smart specialization are some of the commonly cited phrases, to name but a few (Capello & Kroll, 2016). This set of digital tools for democracy are primarily initiated by governments in an attempt to increase efficiency, transparency, accountability, and participation in political processes. Such ways of modernizing government and developing new applications has been the subject of intense study in academic research surrounding participatory and collaborative politics (Mellouli, Luna-Reyes & Zhang, 2014). To date, however, analysis suggests that the ‘hopes and expectations’ of government and other government-sponsored initiators of digital democracy, have yet to be realized (Simon et al., 2017:p. 4). One of the major challenges is the fact that these digital tools regularly fail to achieve a critical mass of participants.[1]

In contrast to the relatively high level of attention afforded to civic tech developed by big companies and governments, to date open-source civic tech co-created or developed as part of a grassroots innovation or social movement has thus far garnered much less attention. Despite the existence of copious amount of such bottom-up activity within the open-source community, evidence of any depth of academic understanding of how and why this tech is made and used, and its potential to bring about change, is lacking; at least, this is the conclusion reached following a review of academic literature published in the medium of English. By focusing specifically on this locus of activity, we seek to address this knowledge gap. In doing so, we distinguish civic tech that has been co-created and co-designed from the bottom-up by civil society, local councils and global volunteers by referring to it as ‘place-based civic tech’. The core question this article aims to address is: does creating a digital space for autonomous self-organization (i.e. place-based civic tech) enable the emergence of a parallel, self-determining and more place-based geography of politics and political action?

Though most studies exploring place-based civic tech remain outside the scope of academia, peer-reviewed research on other forms of decentralized approaches to policymaking is well established both from a grassroots and institutional perspective (Legard, 2015; Newig & Koontz, 2014). Moreover, any current deficit in the coverage of place-based civic tech from within academia, stands in marked contrast to the attention it receives from other sources. Popular media and non-academic articles, for example, widely and regularly report on the developments in this arena (Sahuguet, 2015b; Troncoso, 2018a). By situating this article at the intersection of these studies, we review the significance and implications of this grassroots approach for place-based politics and political action. Serving as a primary evidence base for informing our discussion is the case of a social movement in Spain which is integrally engaged with civic tech. The movement is collectively self-defined by its followers as ‘radical municipalism’. By combining the use of place-based civic tech (online) and place-based organizational models for engagement (offline) the radical municipalism movement is seemingly successfully progressing its agenda; that is, to create ‘radically democratic’ (Weareplanc, 2017) grassroots political processes which are fundamentally distinct from those of government. As such, we question whether radical municipalists are establishing a new place-based geography of politics and political action, but notably one which is simultaneously multi-scalar in impact and reach.

Critical analysis of the radical municipalist movement supports a review of the extent and ways in which creating a digital space that feeds into and feeds off ‘offline’ activities, is capable of creating a unique mode of governance in practice as well as theory. In applying the above stated core research question to this case study, we are also able to address a series of supplementary questions. Firstly, in what way(s) do the distinctive characteristics of the radical municipalist approach – namely, co-design, co-ownership, trans-local collaboration, open-source and combination of online and offline activities – decentralize politics differently or more effectively than a government-led approach? Secondly, to what extent does this approach, in both creating and using digital tools, facilitate a parallel regime of place-based politics and political transformation? And thirdly, when and to what extent might decentralization lead to a more ‘equitable’ or ‘inclusive’ system of politics?

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: having first provided a note on method, we then proceed to reviewing the emergence and spread of place-based civic tech. We are guided in doing so by drawing on scholarship which engages with municipalism. In particular, this includes the work of Murray Bookchin on libertarian municipalism and communalism. Having compared and contrasted this body of work with existing typologies of civic tech, we then focus in on the case of radical municipalism. We consider whether and how this place-based civic tech movement is proving effective in decentralizing, yet simultaneously also expanding the global geography of grassroots politics and political action. We conclude by directly addressing the questions outlined above and end by highlighting areas for future research.

Methodology – beyond the peer-reviewed

Though there have been a surge of studies around the use of digital technology, an analysis of the geography of politics confirms that place-based civic tech is largely missing from academic literature. While some articles refer to municipalism and grassroots civic tech, the majority of reports are found in non-academic sources such as blogs, informal case studies, conference proceedings, hackathons, magazine articles, talks, MeetUps and documentaries. Most civic and emerging tech are such fast-paced fields that experiments precede in-depth study and writing. Therefore, it becomes essential to consult and draw from various sources which are not peer-reviewed or scholarly. Most of the non-scholarly textual sources cited in this article are from blogs and articles endorsed or written by reputable organizations and individuals in the field, classifiable in a methodological sense as expert informants.[2]

For this research, we used ethnographic and participatory observation techniques to explore online environments. Researching online environments has become popular amongst social science researches owing to their ‘increasing importance in everyday life’ (Kurtz et al., 2017:p.1), and accordingly, their importance as sources of research material (Dumova & Fiordo, 2012; Boellstorff, 2012). Furthermore, from the earliest days of the internet, this has been used for community building, collective action and social movement organization (Soon & Kluver, 2014; Harlow, 2012). In accordance, however, with the need to remain mindful of the risks associated with the incorporation of non-scholarly texts, these sources have each been individually cross-checked with others for descriptive facts and for author bias (Harricharan & Bhopal, 2014; Boellstorff, 2012).

Alongside observing the use of online environments by others, the insights and reflections presented in this paper are also a product of an amalgam of various other types of secondary, as well as primary data. Most notably this has included active participation in online discussion forums and slack team channels; as well as, participant observation at stakeholder events such as conferences, hackathons, MeetUps and workshops.[3] The latter generated multiple opportunities for discussion and informal interviews with expert practitioners, government officials, open-source techies, grassroots innovators and researchers. However, owing to their briefness and often inappropriate context for audio recording, conversations are recounted non-verbatim from field notes. Field notes were taken both during and immediately following the events, and later subjected to thematic analysis and interpretation. Methods were adapted for the different contexts primarily consulting the book Participant Observation: A guide for fieldworkers (DeWalt & DeWalt, 2011:pp. 157–210). The insight and evidence obtained from these activities is used in concert with the other sources of data, to critically interpret the scholarly conceptualization of ‘municipalism’ and civic tech, as well as to develop a more nuanced understanding of the radical municipalist movement.

Place-based civic tech & conceptions of municipalism

Civic tech has been used as an umbrella term to describe the range of digital tools that seek to transform the processes of democracy and initiate responsive and inclusive governance mechanisms (Gilman, 2017:p. 744). As Gilman suggests, ‘some definitions of civic technology include for-profit entities while excluding publicly funded projects or the role of government as an incubator and technology innovator’ (Gilman, 2017:p. 745). Though Gilman takes a deliberately ‘narrow’ definition of civic tech as ‘technology that is explicitly leveraged to increase and deepen democratic participation’, all of the examples she cites can be seen as a response by the government to the public appealing against the problems of ‘bad government’ (Microsoft Corporate Blogs, n.d.). By contrast, advocates and practitioners of place-based civic tech claim that it is precisely amongst the responses by civil society to address problems of bad government that far more significant developments in civic tech are to be found.

One of the distinguishing features of place-based civic tech – tech co-created and co-owned by its users – is that it is commonly engaged with by a larger and more diverse population.[4] Implicit within the movement of place-based civic tech is the notion that how, and by whom the tech is created, determines how it will be used. If platforms are created and owned by the government, the features of a platform will reflect those questions deemed most important for consultation on by the government. Contrastingly, if tech is created and ‘owned’ by citizens as part of the global open-source commons, it will reflect issues that are important to the residents of a place and global community. Furthermore, the trust afforded to a platform by the public and the way in which it is perceived, in terms of ‘transparency, bias, privacy and accountability,’[5] may be very different in both scenarios. Public perception and usage is also seemingly influenced by the relationship between offline and online practices. To our understanding, online discussions and complex forms of participation are meant to feed into, and feed off of, the offline processes. For instance, a debate at a neighborhood assembly is informed by, and in turn informs, a decision taken on a corresponding digital platform. The extent to which this online-offline dynamic serves as a core stimulus for fueling the take-up and impact of place-based civic tech is something which we will return to later in this article, in connection with the case study of radical municipalism.

Accounting for the significance of both how the tech is made and how participation is enacted within a place necessitates that due attention is also paid to the dynamic of what we call ‘translocal’ collaboration. In this article, the creation of place-based civic tech is conceptualized as (geographically) unbounded: local activists, organizations, councils and citizens collaborate with the global open-source community and other local communities to create and use civic tech. The movement of place-based civic tech is thus simultaneously global and local, where different place-based movements are united in their diverse ways of practicing participatory and collaborative democracy. Adhering to principles of open-source, they are able to share ways of working and core values, all-the-while adapting the tech and political processes to their place-specific situations. Hence, it is not enough to simply conceptualize civic tech as constituting apolitical tools (Donohue, n.d.; Knight Foundation, 2013), which only embody a political imaginary through their use. Rather, we must acknowledge that the nature of its creation is a political exercise in itself, with this in turn to some extent determining what it will be used for, why, how and by whom.[6] Of direct relevance here is the work of Clément Mabi (Mabi, 2017).

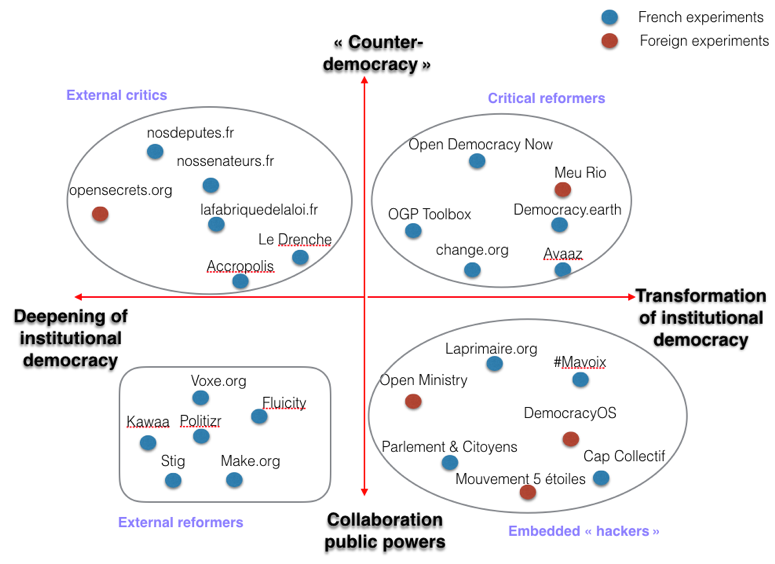

Cartography of families of civic tech (Mabi,2017)

Sketching a ‘rough cartography of civic tech’ (see figure 1), Clément Mabi claims that instead of using the ‘classification of tools’, we should be looking at the ‘political positioning of the technology’ (Mabi, 2017). Such a typology is potentially capable of supporting an understanding of how the tech is created and whether and how it enables place-based politics. Mabi’s categorization is organized around two main tensions and the ‘proximity it maintains with public powers’. On the vertical axis we find projects that seek to transform political institutions from the outside (counter democracy) and those that aim for collaboration with political institutions. On the horizontal axis, are the varying nature of societal transformation that projects aim for – those that want to deepen existing mechanisms and those that want to transform them (see figure 1). Mabi’s typology identifies four clusters or families of initiatives and highlights their respective strategies and goals. The first of these, external critics, are those that focus on deepening representative democracy by increasing transparency of public action and circulation of information. One empirical example of this is Regards Citoyens; this initiative uses a web platform that assembles data concerning the parliamentarians’ activities, displaying it ‘in the form of graphs to allow citizens to follow and evaluate the actions of their representatives’ (Mabi, 2017). The second cluster are external reformers. They are categorized by Mabi as pursuing the aim of enabling direct participation i.e. creating an interface for citizens and political institutions to collaborate through co-creation of public policy, action and education. These mainly include community intelligence platforms or decentralized policy making platforms (Bhagwatwar & Desouza, 2012). The third cluster, critical reformers, are those who mobilize and organize civil society to exert ‘pressure on those who govern’ (Mabi, 2017). ‘Platform cooperatives’, are an example of critical reformers (P2P Foundation, n.d.). A platform coop is ‘an online platform that is organized as a cooperative and owned by its employees customers, users, or other stakeholders’ (Bauwens & Kostakis, 2017). Finally, the fourth cluster identified by Mabi is embedded hackers – those who seek a systematic transformation by working within it, or ‘hack democracy’ by taking responsibilities that are traditionally held by the state. Finland’s Open Ministry (Avoin ministeriö, n.d.) would, for example, fall in this final category, whereby citizens are allowed to propose law and projects directly. Considering these four clusters, a question they prompt here is: in what ways does each of the clusters imagine and seek to enable a different geography of politics and political action? And indeed, in which quartile might the radical municipalist movement of Spain fall?

Both the idea and practice of Mabi’s categories of place-based civic tech can be related, to some extent, to the concept of municipalism. Municipalism has become a container term for a range of identity struggles, protests against certain economic policies and to ‘liberate daily life from the stultification of competitive logic’ (Fowler, 2017:p. 20). According to Fowler, it is a home for ‘the feminsation of politics, resistance to structural racism, the reprioritization of ecology, the reclamation of democracy, the protection of public services, opposition to the commodification of land… to name but a few’ (Fowler, 2017:p. 20). He explains that municipalism creates space for a ‘preguritive politics’ in which the ends are embodied by the means. This ‘New or Radical Municipalism’ is about practicing socio-political processes like horizontalism, collaboration and radical transparency which, while constituting an ‘oppositional politics’, also open up power structures in extant political institutions to make changes directly (Huan, 2010:p. 8). The municipality becomes a self-organized entity capable of actively administrating the ideas and wishes of the local community. In the next section, drawing on the case, we reflect on how radical municipalism can be practiced via a combination of online and offline processes. For now, it is significant to reiterate that radical municipalism as a movement is grounded in the idea of an unbounded translocalism, where diverse struggles and projects, which are united in a ‘political culture’ (Alamany, Caccia & Méndez de Andés, 2017), collaborate with each other to open up extant political institutions.

Synonymous with the idea of municipalism is the socio-political ecologist Murray Bookchin. His concept of ‘libertarian municipalism’ – ‘a social thought that is based on anarchist collectivism’ (Miliszewski, 2017:p. 15) – gives a language to a diverse set of movements practicing direct radical democracy. Though most work on municipalism makes reference to Bookchin’s philosophy, no academic research has previously used it as a frame to rethink the geography of place-based politics from a starting point of civic tech. In sum, libertarian municipalism describes ‘a directly democratic self-government, a political system that is based on radical decentralization and confederalism and supported by ecological philosophy’ (p. 15). Bookchin asserts that ‘ecological dislocations,’ and the environmental crisis in general, are a product of social hierarchies. Furthermore, a radically decentralized, and communitarian ‘oppositional politics’ would comprise of a ‘rigorous analysis of hierarchy’ (Hern, 2016:p. 178). Though Bookchin variously rebranded his political program as social anarchism, social ecology and finally communalism (p. 177), his core proposition remained the same: the city should function as a self-governing commune.

The base ideas of self-organization, collaborative governance and place-based political action are apparent in both Bookchin’s political philosophy and place-based civic tech. In order, however, to establish the wider potential utility of libertarian municipalism as a conceptual frame for better understanding the transformative potential of place-based civic tech with regards to political action and decision-making processes, it is helpful to first further unpack some of its core component parts. According to Bookchin, under the model of libertarian municipalism each commune or city would govern itself through a radical form of direct, face-to-face democracy, which much like the Athenian polis would function without any delegated form of authority. Though Bookchin advocates the idea of decentralized democracy, ‘arguing for local self-reliance and local democratic institutions’ (Hern, 2016:p. 178), his broader political program was confederalist rather than localist. As Fowler explains, Bookchin’s vision is both ‘utopian and practical, short and long term’ where the larger political project would culminate into a ‘global commune of communes’ (Fowler, 2017:p. 24). Notably though, Bookchin’ idea is distinct both from a socialist state-led revolution and an anarchist anti-cooperation ethic. At the crux of his libertarian municipalist project is the need to ‘stop the centralization of economic and political power’ and to ‘disengage cities and towns from the state by mutually confederating with each other and developing some sort of network where resources can be moved back and forth’ (Editors of Kick It Over Magazine, 1986). Fowler contends that Bookchin resists the weaknesses of the historic and contemporary left, which disembeds politics from the everyday and confines it to a ‘negative, anti- and oppositional’ position (Fowler, 2017:p. 25). Instead, Bookchin’s faith lies in the ability and desire of ‘ordinary citizens’ to participate and collaborate in political affairs that directly affect their communities.

David Harvey asserts that, whilst on the one hand, Bookchin’s ideas are ‘by far the most sophisticated radical proposal with the creation and collective use of the commons across a variety of scales’ (Harvey, 2012:p. 85); on the other hand, a major obstacle is to figure out how such a system ‘might actually work and to make sure that it does not mask something very different’(p. 81). Harvey cautions that while radical ‘decentralization and autonomy’ may seem worthwhile objectives, they are also ‘primary vehicles for producing greater inequality through neoliberalization’(p. 83). From his perspective, this place-based system of governance is not a necessary, nor a sufficient condition for an egalitarian society. Rather, class privilege could be reproduced in both a polycentric and place-based political system (Harvey, 2012:p. 83). Harvey asks, ‘how can radical decentralization – surely a worthwhile objective – work without constituting some higher-order hierarchical authority?’ (Harvey, 2012:p. 84) In follow-on, it is similarly important to ask: in which ways does the place-based civic tech deal with the difficulties of enabling equal opportunities within a place? And, if decentralization is not enough, which types of checks and balances can be set in place to make sure socially relegated voices are heard? Taking Harvey’s ideas into account, we must investigate how political partisanship, albeit at a local level, shapes the nature of ‘inclusive’ or ‘participative’ political processes. In other words, how and to what extent do the Spanish citizen platforms incorporate citizens that belong to different socio-economic backgrounds?

Core to the political system of libertarian municipalism is the distinction Bookchin makes between ‘statecraft’ and ‘politics’ (Bookchin, 2000). Statecraft consists of the operations that engage the state – such as control over regulatory apparatus, governance of society with legislators, bureaucracies, armies and police forces. Contrastingly, politics is the ‘civic arena and institutions by which people democratically and directly manage their community affairs’. Owing to the conflation of politics and statecraft, or administration and decision-making, decentralist politics is often constrained by an ongoing state of ‘serious confusion between the formulation of policy and its administration’ (Bookchin, 1995). As Bookchin explains:

‘For a community to decide in a participatory manner what specific course of action it should take in dealing with a technical problem does not oblige all its citizens to execute that policy’ (Bookchin, 1995).

As will be illustrated below, at times initiatives which fall under the umbrella of place-based civic tech seemingly practice both the co-determining and co-administering of policies. It becomes relevant to identify whether this is an unintended conflation or an intentional action, and moreover, to delineate the potential consequences this approach has on the geography of politics.

Fowler asserts that we can gain some conceptual clarity on Bookchin’s ideas by locating them between the political writings of Simon Critchley and Slavoj Žižek. Critchley attributes the contemporary political dysfunction as being rooted in the ‘motivational deficit’ of the contemporary liberal democratic society and institutions (Critchley & James, 2009). He claims that ‘the dissatisfaction of citizens with traditional electoral forms of politics and institutions has led to an explosion of non-electoral engagement and activism’ that has been ‘politically remotivating’(Critchley, 2007:p.90). Critchley’s idea of anarchic metapolitics offers an emotive understanding of the political motivation and mobilization behind radical municipalism and place-based civic tech as a response to a deeply felt injustice. In stark contrast, Žižek’s political imaginary is of a ‘large-scale, wide-reaching, top-down, centralized policymaking and enforcement’ which can counterpose the global and universalizing power of capital (Fowler, 2017:p. 28). Hence, Bookchin’s municipalism can be located between these two poles, neither existing in the niches of society, nor establishing a global socialist state.[7] Doing so in turn allows us to draw similarities with Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein’s world systems perspective and their concept of anti-systemic movements. They explain how it is no longer necessary for global social movements to be contained by the nation-state; rather, they can be transnationally organized as a network (Arrighi, Hopkins & Wallerstein, 1989). For Bookchin, municipalities could function as nodes in a transnationally organized confederacy. The radical municipalist movement similarly evidences a particular transnational collaborative network which shares place-based civic tech, ways of working and practices of direct-radical democracy, albeit not in the form of a confederacy. Furthermore, the creation of open-source place-based civic tech in itself seemingly evidences a transnational collaborative effort.

The case of radical municipalism – an emerging geography of politics and political action?

In order to understand the particularities of a decentralized geography of politics, realized through the utilization of place-based civic tech, it is fruitful to analyze the most advanced experiments in the radical municipalist movement. Spain has been the both the initiator and reference point for the movement, as experiments in self-organization emerged all over the country. The scale of this movement first became publicly evident in 2011, when the Movimiento 15M, or Indignados, saw thousands of Spaniards occupying the squares. They were ‘mobilized by a generalized sense of frustration, indignation and impotency’ that there was no socio-political or economic strategy to deal with the 2008 crisis which ‘prioritized the concerns of the population’ (Castañeda, 2012:p. 1). Around 50,000 demonstrators gathered in Madrid protesting the high unemployment rates,[8] two-party system, welfare cuts, politicians and more generally, the political system, banks and capitalism (El Mundo, 2011). The resulting movement, later to be re-named by its proponents as radical municipalism, was self-organized by activists and ordinary citizens, using open-source civic tech, horizontal forms of participation or direct democracy methods and consensus decision-making.

Historically, Spain has been marked by ‘cooperativism in its anarchist and libertarian forms ever since the second half of the 19th century’ – which could in part explain the support garnered by the more recent citizen platforms – with its online-offline dynamic. However, according to some, there is still a reluctance to move past ‘traditional cooperativism’ and update it with new forms of collaboration and governance (Karatzogianni & Matthews, 2018:p. 13). The May 2015 municipal elections, for example, saw the mayors of Madrid, Barcelona, Zaragoza, Valencia, A Coruña, Cadiz, Pamplona and Santiago de Compostela elected through ‘citizen platforms’ (Garcia, 2017:p. 463). These platforms are distinct political parties in that they use neighborhood assemblies (offline) and democracy platforms (online civic tech) to ‘decide everything from their policy agenda to their organisational structure’ (Baird, 2015). They mark a clear break from party-politics to what we can refer to as ‘platform politics’ of municipalist confluences (Rubio-Pueyo, 2017:p. 8); it is the social movements and activists that own and run the platforms. Furthermore, many cities and municipalities in Spain (and around the world) adapted open-source democracy platforms to suit their place-specific requirements.[9] In effect, a movement of oppositional politics was seeded by ‘remotivated’ civil society as a response to deeply felt injustice (Critchley, 2007). Not only does this highlight the significance of understanding the online/offline dynamic of radical municipalism and how it is operationalized using civic tech; it also merits further investigation of the place-based nature of political organization.

In recent years, Madrid and Barcelona have taken the lead in innovating around participative politics. Operationalizing everything from neighborhood assemblies to using digital platforms to crowdfund policies, their experiences have arguably ‘become a model of political transformation’. Baird et al. explain that the ‘Take back Control’ slogan of Brexit and ‘Forgotten Man’ of Trump are not far removed from the ‘Real Democracy’ of the indignados or the ‘99%’ of Occupy: ‘all speak to the desire for a break with the political Establishment and unfair economic system’ (2016). According to some commentators, Barcelona’s progressive system of politics and ambitious practices in decentralization has seemingly become a focal point of the germinating movement (Gellatly & Rivero, 2018). Activists of Barcelona’s platform, BComú (Barcelona in Common), write that the municipalist movement is addressing the global crisis of neoliberalism by defending an idea of ‘bottom up, feminist and radically democratic change’ (Baird et al., 2016). However, as a local public policy representative argues, radical political players sometimes render the innovation field in Barcelona ‘too ideological’ and not conducive to conversation for those who do not base their initiatives on the pro-commons or cooperative movements (Karatzogianni & Matthews, 2018:pp. 9–10). It is hard to ascertain which is the more accurate depiction of the on the ground situation in Barcelona. However, from our experiences at The International Observatory on Participatory Democracy (IOPD) 2019, it was clear that there is a strong leaning in terms of language and openness towards the cooperative side. More thorough future studies on the partisanship, language and openness within these platforms would help in understanding the nature of inclusiveness (i.e. who really feels included).

Both Madrid and Barcelona’s online platforms, Decide Madrid and Decidim (meaning ‘we decide’ in Catalan) are considered seminal to the digital transformation taking place in the city’s institutions, economy and politics (Ajuntament de Barcelona, n.d.). Xabier Barandiaran, who heads the Decidim project explains that these platforms emphasize the ‘potential of technology to speed up and make possible a more complex participation’. They gather collective intelligence from citizen experts through open meetings and workshops, and generate new political networks oriented to decentralized decision-making, commitment and accountability. These digital platforms are, by design, open, place-based and collaborative (Stark, 2017). Accordingly, the aim and potential success of the movement relies heavily on not only the co-creation of civic tech by communities within the network, but also, on using it to change offline political processes and engagement to enable place-based political action. Another way of looking at this, is that the openness to collective intelligence of ordinary citizens through the platform evidences a ‘prefiguritive politics’ (Fowler, 2017:p. 20) in which the ends, a fairer and more inclusive political system, are embodied by the means, collaboration, transparency and horizontalism.

Barandiaran and many others (see, for example, Pia Mancini (2014) and Jennifer Pahlka (2012), have emphatically claimed that the design and infrastructure of democracy has not been updated in the last two centuries, while socio-technical innovations continually disrupt our society. Online platforms such as Decidim can be understood as an infrastructural update. They aim to fill in many gaps that an outdated political system creates – the digital divide being just as big as the rest. Barandiaran states that these platforms address a series of significant socio-political gaps. Notably, this includes a ‘precariousness gap’, when people are too busy to participate in meetings; a ‘cultural gap’, when people do not have sufficient information and knowledge to contribute to policies; and, a ‘gender gap’, when women are often systematically excluded from public participation (Stark, 2017). By designing the tech with the citizens, radical municipalists claim they are actively attempting to upgrade democracy for the networked age. Furthermore, the independent status of the platform gives the civil society faith in its transparency and accountability, while at the same time redefining the relationship they have with local government. The operationalization of the online/offline dynamic exposes the burgeoning administrative capacity for civil society and activists to self-organize, engage with local government and collaboratively and transparently make decisions concerning their communities. Arguably, this transformation of political practices within municipalities is part of a larger and more diverse story of collaboration where the tech itself is a product of translocal collaborations. For instance, Decidim (see above) and CONSUL (Decide Madrid), the two most used open-source platforms, are commonly free for anyone to download, change and use. They are constantly updated and worked on by a group of global volunteers (i.e. the open-source community), along with those based in the respective city government’s heading the project.

Most open source projects use the online platform Github to co-create. GitHub is a website and service that allows people from around the world to collaboratively work on projects. Very simply, it is a website for version control, meaning it manages and stores revisions of a project tracking contributions made by users.[10] As a report – GitHub: the Swiss army knife of civic innovation? – by Nesta states, Github has already been used in the civic space to manage and serve open data, collaboratively draft legislation and even to facilitate city procurement (Sahuguet, 2015a). In essence, open-source civic tech projects put their basic idea on GitHub and volunteers from around the world help to make that idea a usable software. Furthermore, volunteers can also help update the software, write press releases and guides, make proposals for adding features and so on. However, the most unique feature is that they can ‘fork’ and experiment, freely adding and subtracting features for their own needs.[11] GitHub, and projects on it, seemingly constitute one instance of how decentralized global collaboration can impact a project rooted in a particular place. Moreover, it also reveals why place-based civic tech commonly being open source is seminal in both the spread and professionalism of the radical municipalist movement. If we accept the premise that the digital or online features of radical municipalism (i.e. administrative capacity to self-organize, transparency, accountability and collaboration) address the gaps Barandiaran talks about and actualizes a version of Bookchin’s political imaginary, it becomes clear that the open source ethos has made a large contribution to the radical municipalist movement. CONSUL has already been adapted to many different municipalities and continues to be ‘forked’ and adapted to place-specific feature requirements.[12] If it was not open source, each municipality would have to invest in creating and testing its own tech from scratch.

This open source tech is achieving substantial transformative change in the context of radical municipalism in Spain. Integral to the impact that it is having is the momentum that has been established from regularly bringing together online and offline collaboration exercises. Offline collaboration often takes place at international conferences and hackathons within and beyond the radical municipalist network. For instance, Inteligencia Colectiva para la Democracia or Collective Intelligence for Democracy was two-weeks of prototyping workshops organized by the ParticipaLab in Madrid held for the past three years (the first author attended as a participant in 2019). Through these events multidisciplinary teams gathered, from across the world, to create projects around citizen participation and technology that enables responsive democracy (Medialab-Prado Madrid, 2017). These projects were proposed by local civic activists, supported by institutional actors, after which a team of global volunteers came together to co-create them at the hackathon. They were presented at the Ciudades Democráticas (Democratic Cities) conference in Madrid.[13] While the above was organized to create new civic tech, the ConsulCon was organized to help activists and mayors from around the world adapt and implement the open-source participation tool Consul to their place-specific needs (Anon, n.d.) (the first author attended both the events in 2018 and 2019). Important to note here is that these events have a strong open-source ethos in that there is a unique culture of sharing, mutual aid, openness and peer-to-peer collaboration.[14]

Similarly, Fearless Cities or International Municipalist Summit 2017 in Barcelona was a gathering of municipalist movements, building global networks of solidarity and support (Anon, n.d.). Organized by Barcelona en Comú, the city’ elected platform (BComú Global, 2017), it was a showcase of numerous experiments, with civic tech taking power at a city level to empower citizens’ movements worldwide. In some blogs, it was stated that the event was ‘the ‘coming out’ party for a new global social movement’: radical municipalism (Reyes & Russell, 2017a). The meeting brought together 700 mayors, councilors, activists, and citizens from more than 180 cities in more than 40 countries, across five continents, including representatives from approximately 100 citizen platforms (Gellatly & Rivero, 2018). The belief that culminated into this summit, as well as prior mentioned hackathons, was that cities and towns ‘face adversaries who cross borders’, this being a reference to the democratic deficit imposed by the dominant socio-political and economic system. Hence, the response must be transnational, in that ‘the municipalist movement must be internationalist’ (Baird et al., 2016). In the context of this article, we understand this as ‘place-based political action must be globally oriented’, whereby a geography of political action can be created as a product of solidarity, organization, cooperation and experience shared across national borders. Moreover, the rhetoric of both harnessing the power of local municipal governments and transnational networks is in keeping with Bookchin’s idea of neither laying in the niches of society, nor advocating a global state apparatus. Accordingly, it illustrates how the radical municipalist movement – which refers to ways of working and harnessing the collective intelligence of activists and civil society around the world, more than a formal structure – lays emphasis on enabling new practices of collaboration and politics through collaboratively producing open-source civic tech, and place-based political processes.

Synthesizing remarks: decentralization, independence & equitability

To summarize the discussion thus far, for those who identify with the radical municipalist approach to the expansion of place-based civic tech, a purported common aim is to develop open-source digital tools which are co-designed, co-owned and co-managed by the users (i.e. citizens, local authorities, and a group of global volunteers). Furthermore, the political scale of implementation of online tools and offline processes depends on the needs of the particular neighborhood; the places and scales of operation simultaneously become part of a global network of civic tech and municipal activity. Thus, despite the possibility and likelihood for local variation to be a constant feature of the ways in which these actors bring together, practice and situate their on- and off-line activities, they are simultaneously able to collaborate with each other on a global scale. Notable here is their default ‘open-source’ ethos, not just with regards to the technology, but also for sharing experiences, administrative and technical support, and toolkits for experimentation. Hence, the case of radical municipalism in Spain and its utilization of place-based civic tech suggests that the place-sensitive online/offline dynamic, open source ethos, and an ‘oppositional politics’ to the dominant political regime are the particularities of this geography of politics.

Turning our attention now to the second supplementary research question, concerning the independent system of politics, we begin by revisiting the radical municipalist’s claim to encourage the idea of self-organization and self-governance. The latter is pursued, not simply through a series of transparent commitments with local authorities, but also by creating spaces and opportunities for place-based civic tech initiatives to function and experiment irrespective of state involvement. Moving beyond the nation-state and ‘taking power back’ through radical direct democracy is a uniting theme in the radical municipalist movement. However, to what extent have towns, to paraphrase Bookchin, ‘disengaged from the state and confederated with each other to decentralize economic and political power’? Advocates of radical municipalism are often questioned on the ‘level of responsibility’ versus the ‘level of power’ of municipalities (Troncoso, 2018b). Joan Subirats, one of the founders of BComú, explains that responsibility is quite high in spite of the fact that power is quite low. This is one of the reasons BComú is trying to spread the municipal movement across Catalonia. However, local political intervention can also be carried out through a global network of cities. For instance, Barcelona, Berlin, Amsterdam and New York are making alliances against Airbnb (Largave, 2017), while also creating fairer alternatives like Fairbnb, where the platforms profits are invested back into the community (Anon, n.d.). BComú writes ‘given that we face adversaries who cross borders, our response must also be transnational’ (Baird et al., 2016). As Subirats emphatically confirms, the municipalist movement need not ‘be limited by the idea that there are no legal powers’ (Troncoso, 2018b).

More provocatively, cities can also take political action by-passing their obligations to the nation state. An important example here, is that of cities which are willing to take in refugees even if the Spanish government blocks refugee entry. Cities could unilaterally welcome a certain number resulting in a situation whereby they would be disobeying the national government, yet paradoxically at the same time, obeying the European scheme on refugee relocation (Troncoso, 2018b). As Troncoso and Subirats agree, not only does this signal the relevance of transnational organizations like EuroCities which help promote learning and sharing between cities, but also new institutional arrangements and operational interfaces that circumvent the dominant policy regime (Troncoso, 2018b). These initiatives further contribute to a translocal geography of political action. They show how politico-economic decision making can begin to be disengaged from the national powers and replaced instead by a coordinated effort with cities ‘confederating’ with each other on specific issues.

Considering such political action which bypasses the nation-state, radical municipalists also show how changes in the perception of power can lead to a form of translocal politics. This geography of politics and political action can be thought of as one that manages to channel the frustration and mobilization from the streets into the institutions and government, diminishing the idea that citizens and activists cannot enact political change. Seemingly, it is the conceptualization of radical municipalism as a ‘political culture’ that enables it to be situated between the centralized institutional spheres and extra-institutional political organizing and protest movements (Caccia, 2017). As writers of the anti-systemic movements would claim, it is precisely the fact that radical municipalists take their protest to the institutions, which opens up the possibility of overcoming the ‘noncontinuity of rebellion’ (Arrighi, Hopkins & Wallerstein, 1989:p. 29). Hence, rather than simply creating a ‘parallel’ political geography, we observe that radical municipalists aspire to create a significant, systemic and sustainable change by actively taking back control of their local institutions. They disengage from the national institutions, while simultaneously taking control of local institutions, by operationalizing translocal networks of solidarity, collaboration and sharing.

To what extent then, to return to our third subsidiary question, is the implicit aim of creating a more equitable system of politics achieved through practices which reunify politics with everyday life? Purportedly, as discussed earlier, this has achieved an actively engaged citizenry, mobilizing the voiceless and feminizing politics. According to the Mayor of Madrid, Manuela Carmena, for example, the radical transparency enabled by civic tech brings “psychological security…so that we are all constantly accountable for out political impulses”(DR)[15]. Transparency also provides fertile soil for debate and constructive politics, where responsibility is distributed across society. The municipalist movement is one where “citizens become leading forces of change” (DR). At the 2017 Democratic Cities conference, in a discussion with Ada Colau, the mayor of Barcelona, Carmena expressed a desire to move beyond transparency and simple participation: “we must promote collaborative governance”(DR). Jointly, they emphatically explain that this is a “moment to engage” where they must enlarge the participation processes and test “the co-production and co-responsibility of city commons” (DR). Digital tools help create the organizational capacity, transparency, responsibility and commitment required for grassroots political mobilization. This also points in the direction of work done by GovLab’s Beth Simone Noveck, on the need to break the professionalism of governance and allow the emergence of citizen experts (Fritzen, 2017). She explains that we need to ‘tap into know-how’ arising from ‘the collective intelligence of our communities’, and accordingly, ‘draw power from the participation of the many, rather than the few’ (Noveck, 2016). Using the knowledge of citizen experts and reunification of politics with the everyday life are also essential features of Bookchin’s idea of municipalism. Though digital tools can facilitate collaborative democracy, they cannot alone create the ‘remotivated’ society (Critchley, 2007).

In Barcelona, with BComú’s election, we see that a call for reunification of politics with everyday life also lead to a reversal in the vote share with 40% more votes from the poorest regions of the city. This could serve as an indicator of how engagement changes when local political decision-making and implementation of actual projects is opened up (P2P Foundation, 2018). At the same time, the government of Madrid (Ahora Madrid) teamed up with newDemocracy and ParticipaLab to design a ‘citizen-initiated referendum process’ in which citizen juries will apply a public judgement on which proposals will be sent to a citywide referendum (newdemocracy, 2018). A 57-person council selected randomly using Sortition (Sortition Foundation, 2019) from many different backgrounds and professions will first explore the proposals and decide whether to go to referendum. Pablo Soto, a counselor in Madrid, explained that the idea is to democratize the entire process of choosing projects on the platform: we want to let people “change the agenda” of what happens in the city. Looking back at Harvey’s points on partisanship and reproducing class-based inequalities, it could be argued that Madrid is taking steps to address these problems[16].

In parallel to Madrid’s initiatives to mobilizing ordinary citizens and giving a voice to the voiceless, Barcelona’s municipal government makes claims of feminizing politics. As Laura Peréz, the Councilor for Feminism and LGBTI affairs asserts, ‘we don’t just want one department designing policies against gender-based violence or specific policies and services for women’ (Government of Change in Barcelona, 2017). Rather, they want the approach integrated in all departments, where all citizens, activists and entrepreneurs of all ages and genders are included and accounted for in the design of policies, public services and infrastructure. As such, an important feature of feminizing politics is to bring empathy to governance. Colau (the mayor of Barcelona) herself claims that she aims to feminize politics, not simply by putting more women in office, but through striving to realign values and ‘by demonstrating that cooperation is more effective and enjoyable than competitiveness’ (Burgen, 2015)[17]. For instance, Colau meets citizens in different neighborhoods around the city every two weeks where the elderly, immigrants and the youth can freely debate and criticize the actions and policies of government, while also planning the initiation of tangible projects. In doing so, Colau reportedly practices a feminized ‘political style’ that ‘openly expresses doubts and contradictions’(Reyes & Russell, 2017b) and begins with a politics that listens rather than confronts (Beatley, 2017). As a report on municipalism explains, the appeal of her practices resides in the insistence on ideas of dialogue, empathy and a sort of collectively built leadership which in turn results in ‘the figure of a leader…as a shared symbol’ (Rubio-Pueyo, 2017:p. 13), as opposed to political representation. While we lack primary data to evidence these claims, it is worth noting that (at the time of writing) there are 30,676 participants, 14 assemblies, 14 ongoing processes and 13,449 proposals out of which 9200 have been accepted on Barcelona’s Decidim online platform; there are also a number of active assemblies, including one dedicated to voicing the proposals of the children of the city.

Conclusion

At the start of the article, we asked whether creating a digital space for self-organization allows for the emergence of a self-determining and more place-based geography of politics and political action. By critically reviewing the initiatives and practices of the radical municipalist movement in Spain, we have seen how there is a passionate, motivated and diverse community working to enhance collaboration, community, mutual aid, solidarity and political engagement and lessen the precariousness, cultural and gender gaps identified earlier. Moreover, we can observe a shift in the history of disconnection between citizens, social movements and local governments which is a core feature of Bookchin’s political imaginary. Notably, the online democracy platforms evidently creates organizational capacity for self-organization and administrative capacity for sharing experiences and learning. Arguably, without the operationalization of civic tech, the transparency and accountability of political decision-making and impulses would not be possible in the same way or degree. In that, the spread of the municipalist network as diverse, yet united movements of direct, local self-government owes much to place-based civic tech and the global open-source community. It gives them a united front that operates below and beyond the nation-state. The online network and municipal confluences also unbound the dichotomy of global-local by using a combination of subnational and transnational mechanisms.

Our conclusion is not that place-based civic tech, and the municipalist movement specifically, is radicalizing democracy. Rather, by finding a mix of old and new ways, it is holding the present structures and institutions of government accountable for their use of the concept of democracy. To respond directly to the main research question, it cannot be said that the digital alone creates the space for autonomous self-organization; rather the particular type of political processes that are implemented forms an integral part of a place-based geography of politics and political action. The case of radical municipalism is evidencing a clear and compelling narrative of taking power back in a plural and human scaled way (Burke, 2016), which is empathetic, open, transparent and dedicated to uniting everyday life with political civic life. We ascribe part of the success of this movement to the incorporation of place based civic tech. This, together with its open-source ethos, broadens the organizational capacity and allows for the emergence of new online/offline political processes by updating the infrastructure of democracy. The hope of radical municipalists is that it will result in a transformation of democracy, ushering in a culture of place-based politics and active citizenship through decentralizing the geography of politics and political action.

The furthering of this movement could be the rippling out of a proto-confederation or a politico-economic network that ‘disengage’ municipalities from the national level, while fostering economic autonomy which could influence the next tiers of government. To return to the starting point of the article, there is a lot of attention given to collaborative democracy initiatives sponsored by the government. In contrast, we advocate for more interdisciplinary research, which develops and encourages the decentralization of politics and political action and sheds light on the initiatives currently below the radar of academia. As a step towards this, connecting these political movements with other experiments in decentralization like blockchain projects, commons initiatives, and P2P governance is, arguably, a fruitful next step on the agenda both for researching and for the practice of civic technologies.

Bibliography

Adler, M.S., Fischer, M.G. & McFarlane, M.N. (2017) Technology Is Key to Local Citizen Engagement. [Online]. 2017. Government Technology. Available from: http://www.govtech.com/opinion/Technology-Is-Key-to-Local-Citizen-Engagement.html [Accessed: 30 January 2018].

Ajuntament de Barcelona (n.d.) Decidim Barcelona | Barcelona Digital City. [Online]. 2018. Available from: http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/en/digital-empowerment/democracy-and-digital-rights/decidim-barcelona [Accessed: 23 January 2018].

Alamany, E., Caccia, B. & Méndez de Andés, A. (2017) Workshop 10: Municipalism for Dummies. [Online]. 2017. Fearless Cities. Available from: http://2017.fearlesscities.com/municipalism-for-dummies/ [Accessed: 21 May 2018].

Anon (n.d.) CONSUL – Free software for citizen participation. [Online]. Available from: http://consulproject.org/en/ [Accessed: 23 January 2018a].

Anon (n.d.) ConsulCon « Democratic Cities. [Online]. Available from: http://democratic-cities.cc/consulcon/ [Accessed: 4 March 2018b].

Anon (n.d.) FairBnB – A smart and fair solution for community powered tourism. [Online]. Available from: https://fairbnb.coop/ [Accessed: 16 March 2018c].

Anon (n.d.) Fearless Cities – International Municipalist Summit. [Online]. Available from: http://fearlesscities.com/ [Accessed: 13 February 2018d].

Arrighi, G., Hopkins, T.K. & Wallerstein, I.M. (1989) Antisystemic movements. [Online]. Verso. Available from: https://bibdata.princeton.edu/bibliographic/572946 [Accessed: 23 May 2018].

Attard, J., Orlandi, F., Scerri, S. & Auer, S. (2015) A systematic review of open government data initiatives. Government Information Quarterly. [Online] 32 (4), 399–418. Available from: doi:10.1016/j.giq.2015.07.006.

Avoin ministeriö (n.d.) Open Ministry – Crowdsourcing Legislation. [Online]. Available from: http://openministry.info/ [Accessed: 28 April 2018].

Baird, K.S. (2015) Rebel cities: the citizen platforms in power. [Online]. 2015. Red Pepper. Available from: https://www.redpepper.org.uk/rebel-cities-the-citizen-platforms-in-power/ [Accessed: 25 May 2018].

Baird, K.S., Bárcena, E., Ferrer, X. & Roth, L. (2016) Why the municipal movement must be internationalist. [Online]. 2016. Medium. Available from: https://medium.com/@BComuGlobal/why-the-municipal-movement-must-be-internationalist-fc290bf779f3 [Accessed: 13 February 2018].

Bani, M. (2012) Crowdsourcing Democracy: The Case of Icelandic Social Constitutionalism. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Online] Available from: doi:10.2139/ssrn.2128531.

Bauwens, M. & Kostakis, V. (2017) Cooperativism in the digital era, or how to form a global counter-economy. [Online]. 2017. openDemocracy. Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/digitaliberties/michel-bauwens-vasilis-kostakis/cooperativism-in-digital-era-or-how-to-form-global-counter-economy [Accessed: 5 March 2018].

BComú Global (2017) Barcelona En Comú: party vs. movement. [Online]. 2017. Medium. Available from: https://medium.com/@BComuGlobal/barcelona-en-comú-party-vs-movement-a80ab308f460 [Accessed: 13 February 2018].

Beatley, M. (2017) Barcelona’s mayor is on a quest to ‘feminize’ politics amid independence debate. [Online]. 2017. Public Radia International (PRI). Available from: https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-10-26/barcelona-s-mayor-quest-feminize-politics-amid-independence-debate [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

Bekkers, V., Dijkstra, G. & Fenger, M. (2007) Governance and the Democratic Deficit. [Online]. Routledge. Available from: doi:10.4324/9781315585451 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Bhagwatwar, A. & Desouza, K.C. (2012) Community intelligence platforms: The case of open Government. [Online]. Available from: https://asu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/community-intelligence-platforms-the-case-of-open-government [Accessed: 12 February 2018].

Boellstorff, T. (2012) Ethnography and virtual worlds : a handbook of method. Princeton University Press.

Bookchin, M. (1995) Libertarian Municipalism: The New Municipal Agenda. [Online] This artic. Available from: http://www.social-ecology.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Libertarian-Municipalism-The-New-Municipal-Agenda.pdf [Accessed: 5 December 2017].

Bookchin, M. (2000) Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism. In: Left Green Perspectives (ed.). The Politics of Social Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism. [Online]. 2000 Institute for Social Ecology. p. Number 41. Available from: http://social-ecology.org/1999/08/thoughts-on-libertarian-municipalism/ [Accessed: 6 December 2017].

Burgen, S. (2015) Barcelona mayor-elect Ada Colau calls for more ‘feminised’ democracy | World news | The Guardian. [Online]. 2015. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/07/barcelona-mayor-ada-colau-feminised-democracy [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

Burke, S. (2016) Placemaking and the Human Scale City. [Online]. 2016. Project for Public Spaces. Available from: https://www.pps.org/article/placemaking-and-the-human-scale-city [Accessed: 25 June 2018].

Caccia, G. (2017) From Citizen Platforms to Fearless Cities: Europe’s New Municipalism. [Online]. 2017. Political Critique. Available from: http://politicalcritique.org/world/2017/from-citizen-platforms-to-fearless-cities-europes-new-municipalism/ [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

Capello, R. & Kroll, H. (2016) From theory to practice in smart specialization strategy: emerging limits and possible future trajectories. European Planning Studies. [Online] 24 (8), 1393–1406. Available from: doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Castañeda, E. (2012) The Indignados of Spain: A Precedent to Occupy Wall Street. Social Movement Studies. [Online] 11 (3–4), 309–319. Available from: doi:10.1080/14742837.2012.708830 [Accessed: 25 May 2018].

Chadwick, A. (2003) Bringing E-Democracy Back in: Why it Matters for Future Research on E-Governance. Social Science Computer Review. [Online] 21 (4), 443–455. Available from: doi:10.1177/0894439303256372.

Cillero, M. (2017) What does it mean to feminise politics? [Online]. 2017. Political Critique. Available from: http://politicalcritique.org/opinion/2017/feminise-politics-gender-equality/ [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

Critchley, S. (2007) Infinitely demanding : ethics of commitment, politics of resistance. Verso.

Critchley, S. & James, S. (2009) Infinitely Demanding Anarchism: An Interview with Simon Critchley. [Online]. Available from: https://philpapers.org/rec/CRIIDA [Accessed: 21 May 2018].

Decidim (n.d.) Free Open-Source participatory democracy for cities and organizations. [Online]. Available from: https://decidim.org/ [Accessed: 1 June 2018].

DeWalt, K.M. & DeWalt, B.R. (2011) Participant observation : a guide for fieldworkers. [Online]. Rowman & Littlefield. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Participant+Observation%3A+A+Guide+for+Fieldworkers&oq=Participant+Observation%3A+A+Guide+for+Fieldworkers&aqs=chrome..69i57.419j0j1&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 [Accessed: 17 January 2019].

Donohue, S. (n.d.) Engines of Change – What Civic tech can learn from social movements. [Online] Available from: http://enginesofchange.omidyar.com/docs/OmidyarEnginesOfChange.pdf [Accessed: 7 February 2018].

Dumova, T. & Fiordo, R. (2012) Preface – Blogging in the Global Society: Cultural, Political and Geographical Aspects. [Online]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2278694 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Editors of Kick It Over Magazine (1986) Radicalizing Democracy: An Interview with Murray Bookchin. [Online]. 1986. Kick It Over. Available from: http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bookchin/raddemocracy.html [Accessed: 21 May 2018].

EITB (2011) Unemployment in Spain rises sharply to 21.3 percent | EITB News. [Online]. 2011. News. Available from: https://www.eitb.eus/en/news/detail/646452/unemployment-spain-rises-sharply-213-percent/ [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Festival of Civic Tech for Democracy @ PDF CEE 2018 (2018) Miguel Arana Catania: Consul – Open Source Digital Tools not Only for Participatory Budgeting – YouTube. [Online]. 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFN4mfKYHtw [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Finley, K. (2012) What Exactly Is GitHub Anyway? [Online]. 2012. TechCrunch. Available from: https://techcrunch.com/2012/07/14/what-exactly-is-github-anyway/ [Accessed: 12 February 2018].

Fowler, K. (2017) Tessellating Dissensus: Resistance, Autonomy and Radical Democracy – Can transnational municipalism constitute a counterpower to liberate society from neoliberal capitalist hegemony? [Online]. Schumacher College. Available from: https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:18667/ [Accessed: 14 May 2018].

Friedman, U. (2016) From Trump to Brexit: Trust in Government Is Collapsing Around the World –. [Online]. 2016. The Atlantic. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/07/trust-institutions-trump-brexit/489554/ [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Fritzen, S.A. (2017) Smart citizens, smarter state: The technologies of expertise and the future of governing. Beth Simone Noveck. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2015. Governance. [Online] 30 (1), 158–159. Available from: doi:10.1111/gove.12262 [Accessed: 1 December 2017].

Garcia, B. (2017) New citizenship in Spain: from social cooperation to self-government. Citizenship Studies. [Online] 21 (4), 455–467. Available from: doi:10.1080/13621025.2017.1307603 [Accessed: 25 May 2018].

Gellatly, J. & Rivero, M. (2018) Radical Municipalism: Fearless Cities. [Online]. 2018. P2P Foundation – Stir to Action. Available from: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/radical-municipalism-fearless-cities/2018/04/03 [Accessed: 25 May 2018].

Gilman, H.R. (2017) Civic Tech For Urban Collaborative Governance. PS: Political Science & Politics. [Online] 50 (03), 744–750. Available from: doi:10.1017/S1049096517000531 [Accessed: 4 December 2017].

GitHub (2016) What is GitHub? [Online]. 2016. YouTube. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w3jLJU7DT5E [Accessed: 12 February 2018].

GitHub Help (n.d.) Fork A Repo – User Documentation. [Online]. Available from: https://help.github.com/articles/fork-a-repo/ [Accessed: 12 March 2018].

Government of Change in Barcelona (2017) TWO YEARS LATER (Subt: Eng, Spa, Fre, Ger, Ita). [Online]. 2017. Youtube. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HivzxLW_t6Q&list=PL2kTIRA0e_-hftabecS6J14_MR_MC62oQ&index=13&t=57s [Accessed: 16 March 2018].

Harlow, S. (2012) Social media and social movements: Facebook and an online Guatemalan justice movement that moved offline. New Media & Society. [Online] 14 (2), 225–243. Available from: doi:10.1177/1461444811410408 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Harricharan, M. & Bhopal, K. (2014) Using blogs in qualitative educational research: an exploration of method. International Journal of Research & Method in Education. [Online] 37 (3), 324–343. Available from: doi:10.1080/1743727X.2014.885009 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Harvey, D. (2012) Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. [Online]. New York. Available from: doi:303.3’72–dc23 [Accessed: 5 December 2017].

Hern, M. (2016) What a city is for: Remaking the polics of displacement. [Online]. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9609291639&site=ehost-live [Accessed: 18 January 2018].

Huan, Q. (2010) Eco-socialism as politics : rebuilding the basis of our modern civilisation. Springer.

Karatzogianni, A. & Matthews, J. (2018) Platform Ideologies: Ideological Production in Digital Intermediation Platforms and Structural Effectivity in the “Sharing Economy”. Television & New Media. [Online] 152747641880802. Available from: doi:10.1177/1527476418808029 [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Kelly, K. (2010) What technology wants. Viking.

Knight Foundation (2013) The Emergence of Civic Tech : Investments in a Growing Field. [Online] (December), 30. Available from: http://www.knightfoundation.org/media/uploads/publication_pdfs/knight-civic-tech.pdf.

Kurtz, L.C., Trainer, S., Beresford, M., Wutich, A., et al. (2017) Blogs as Elusive Ethnographic Texts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. [Online] 16 (1), 160940691770579. Available from: doi:10.1177/1609406917705796 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Largave, K. (2017) 8 Cities Cracking Down on Airbnb – Condé Nast Traveler. [Online]. 2017. Condé Nast Traveler. Available from: https://www.cntraveler.com/galleries/2016-06-22/places-with-strict-airbnb-laws [Accessed: 16 March 2018].

Layne, K. & Lee, J. (2001) Developing fully functional E-government: A four stage model. Government Information Quarterly. [Online] 18 (2), 122–136. Available from: doi:10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00066-1.

Legard, S. (2015) Scaling Up: Ideas about Participatory Democracy. 2015. New Compass.

Mabi, C. (2017) Citizen Hacker. [Online]. 2017. Books & Ideas – translated by Renuka George. Available from: http://www.booksandideas.net/Citizen-Hacker.html [Accessed: 9 February 2018].

Mancini, P. (2014) Pia Mancini: How to upgrade democracy for the Internet era. [Online]. 2014. TED Talks – TEDGlobab 2014. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/pia_mancini_how_to_upgrade_democracy_for_the_internet_era [Accessed: 23 January 2018].

Medialab-Prado Madrid (2017) Collective Intelligence for Democracy 2017. [Online]. 2017. Available from: http://medialab-prado.es/article/collective-intelligence-for-democracy-2017-call-for-collaborators?lang=en [Accessed: 12 February 2018].

Medialab Prado (2017) Selected projects: Collective Intelligence for Democracy 2017 – Medialab-Prado Madrid. [Online]. 2017. Available from: http://medialab-prado.es/article/selected-projects-collective-intelligence-for-democracy-2017 [Accessed: 13 February 2018].

Mellouli, S., Luna-Reyes, L.F. & Zhang, J. (2014) Smart government, citizen participation and open data. Information Polity. [Online] 19, 1–4. Available from: doi:10.3233/IP-140334 [Accessed: 7 February 2018].

Microsoft Corporate Blogs (n.d.) Civic Tech: Solutions for governments and the communities they serve – Microsoft on the Issues. [Online]. 2014. Available from: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2014/10/27/civic-tech-solutions-governments-communities-serve/ [Accessed: 29 January 2018].

Miliszewski, K. (2017) Libertarian Municipalism In Murray Bookchin’s Social Thought. Torun Social Science Review. [Online] 2 (1). Available from: https://tbr.wsb.torun.pl/index.php/TSSR/article/view/108 [Accessed: 9 January 2018].

El Mundo (2011) Miles de personas exigen dejar de ser ‘mercancías de políticos y banqueros’ | España. [Online]. 2011. elmundo.es. Available from: https://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2011/05/15/espana/1305478324.html [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Network Impact (2017) Civic Tech: How to Measure Success? [Online]. 2017. Available from: http://www.networkimpact.org/civictecheval/ [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

newdemocracy (2018) The City of Madrid Citizens’ Council – newDemocracy Foundation. [Online]. 2018. Available from: https://www.newdemocracy.com.au/2018/11/15/the-city-of-madrid-citizens-council/ [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Newig, J. & Koontz, T.M. (2014) Multi-level governance, policy implementation and participation: the EU’s mandated participatory planning approach to implementing environmental policy. Journal of European Public Policy. [Online] 21 (2), 248–267. Available from: doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.834070 [Accessed: 19 January 2018].

Noveck, B.S. (2016) Could crowdsourcing expertise be the future of government? [Online]. 2016. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2016/nov/30/could-crowdsourcing-expertise-be-the-future-of-government [Accessed: 16 March 2018].

Oliver, J. (2011) El desempleo juvenil alcanza en España su mayor tasa en 16 años. [Online]. 2011. La Voz de Galicia. Available from: https://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/economia/2011/04/02/desempleo-juvenil-alcanza-espana-mayor-tasa-16-anos/0003_201104G2P26991.htm [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

P2P Foundation (2018) Barcelona en Comú. [Online]. 2018. Available from: http://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Barcelona_en_Comú [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

P2P Foundation (n.d.) You searched for platform cooperativism | P2P Foundation. [Online]. Available from: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/?s=platform+cooperativism [Accessed: 5 March 2018].

Pahlka, J. (2012) Jennifer Pahlka: Coding a better government. [Online]. 2012. TED Talk | TED2012. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/jennifer_pahlka_coding_a_better_government [Accessed: 23 January 2018].

Reyes, O. & Russell, B. (2017a) Fearless Cities: the new urban movements. [Online]. 2017. Red Pepper. Available from: https://www.redpepper.org.uk/fearless-cities-the-new-urban-movements/ [Accessed: 15 January 2018].

Reyes, O. & Russell, B. (2017b) How Progressive Cities Can Reshape the World — And Democracy – FPIF. [Online]. 2017. Foreign Policy in Focus. Available from: https://fpif.org/how-progressive-cities-can-reshape-the-world-and-democracy/ [Accessed: 29 May 2018].

Rubio-Pueyo, V. (2017) Municipalism in Spain: From Barcelona to Madrid, and Beyond Municipalism in Spain. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung – New York Office. [Online] Available from: http://www.rosalux-nyc.org/wp-content/files_mf/rubiopueyo_eng.pdf [Accessed: 22 January 2018].

Sahuguet, A. (2015a) GitHub: the Swiss army knife of civic innovation? | Nesta. [Online]. 2015. Governance Lab Academy. Available from: https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/github-swiss-army-knife-civic-innovation [Accessed: 6 February 2018].

Sahuguet, A. (2015b) Tech4Labs Issue 3: Digital tools for participatory democracy. [Online]. 2015. Nesta. Available from: https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/tech4labs-issue-3-digital-tools-participatory-democracy [Accessed: 15 January 2018].

Simon, J., Bass, T., Boelman, V., Mulgan, G., et al. (2017) Digital Democracy The tools transforming political engagement. [Online] Available from: https://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/digital_democracy.pdf [Accessed: 17 April 2018].

Soon, C. & Kluver, R. (2014) Uniting Political Bloggers in Diversity: Collective Identity and Web Activism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. [Online] 19 (3), 500–515. Available from: doi:10.1111/jcc4.12079 [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Sortition Foundation (2019) What is sortition? [Online]. 2019. Available from: https://www.sortitionfoundation.org/what_is_sortition [Accessed: 15 January 2019].

Stanford University. & Center for the Study of Language and Information (U.S.) (2009) Philosophy of Technology. [Online]. 2009. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/technology/#AppEthTec [Accessed: 13 June 2018].

Stark, K. (2017) Barcelona’s Decidim Offers Open-Source Platform for Participatory Democracy Projects. [Online]. 2017. Sharable. Available from: https://www.shareable.net/blog/barcelonas-decidim-offers-open-source-platform-for-participatory-democracy-projects [Accessed: 21 May 2018].

Troncoso, S. (2018a) Coops Viadriana. A new illustrated mag about Platform Cooperativism. [Online]. 2018. P2P Foundation. Available from: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/coops-viadriana-a-new-illustrated-mag-about-platform-cooperativism/2018/02/13 [Accessed: 5 March 2018].

Troncoso, S. (2018b) The City as the New Political Centre. [Online]. 2018. P2P Foundation. Available from: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/the-city-as-the-new-political-centre/2018/03/01 [Accessed: 16 March 2018].

Weareplanc (2017) Radical Municipalism: Demanding the Future. [Online]. 2017. We are Plan C. Available from: https://www.weareplanc.org/blog/radical-municipalism-demanding-the-future/ [Accessed: 22 January 2018].

Wike, R., Simmons, K., Stokes, B. & Fetterolf, J. (2016) Current government systems rated poorly by many. [Online]. 2016. Pew Research Center. Available from: http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/10/16/many-unhappy-with-current-political-system/ [Accessed: 31 May 2018].

Notes

[1] Information from a series of field notes at Open Government Workshops and semi-structured interviews with expert practitioners. For information on achieving critical mass as an integral part of the success of civic tech, refer to (Network Impact, 2017)

[2] For instance blogs posted by the P2P foundation or Nesta, reports from local councils and activists of the radical municipalist movement in Spain.

[3] Conferences such as the Democratic Cities (2018 and 2019), gofod3 Cardiff (2018); Hackathons such as (Collective Intelligence for Democracy (2019); Civic tech – collaborative democracy (P2P) events such as Ouishare fest Paris (2017) where workshops were conducted; Slack groups on direct democracy and P2P applications and many miscellaneous Meetups with activists and researchers.

[4] ‘The city council hosted several organizing events to decide on a strategic plan, and nearly 40,000 people and 1,500 organizations contributed 10,000 suggestions’. (Stark, 2017)

[5] These are some of the reiterated concerns and topics of discussion brought up in the online discussion forums and blogs.

[6] Along with the above studies which refer in particular to civic tech – the understanding of morality, agency and intentionality in tech has been a longstanding debate in the philosophy of technology. Refer to:(Kelly, 2010; Stanford University. & Center for the Study of Language and Information (U.S.), 2009)

[7] The credit for making this link remains with (Fowler, 2017)

[8] 21.3% (5 million people) unemployment, while youth unemployment was 43.5%. (Oliver, 2011; EITB, 2011)

[9] For an up to date list of municipalities where open-source platforms are being used, it is important to visit their websites: (Anon, n.d.; Decidim, n.d.)

[10] For more information on GitHub, please refer to: (GitHub, 2016; Finley, 2012)

[11] Forking means to copy the repository and freely experiment and change it without affecting the original. For a more elaborate definition, consult: (GitHub Help, n.d.)

[12] CONSUL and many other democracy platforms such as Decidim and Democracy OS harness the simple infrastructure of the internet and employ decision-making tools to transform the interfaces between citizens and government, increase transparency, design accountability and enable self-organization and management.

[13] For a complete list of projects please refer to: (Medialab Prado, 2017)

[14] For more information on Consul and Madrid’s open-source ethos, refer to Miguel Arana Catania’s interview (Festival of Civic Tech for Democracy @ PDF CEE 2018, 2018)

[15] All quotations from diary reflections of the first author at the Democratic Cities Conference Madrid 2017 below are labelled (DR)

[16] Notes taken by the first author at the The International Observatory on Participatory Democracy (IOPD) 2018 — Roundtable 3-D: Practices in direct democracy 2

[17] For more information on feminizing politics, refer to: (Cillero, 2017)

About the authors

S.O. Husain is a Marie-Curie Research Fellow at the EU project SUSPLACE (sustainable place-shaping), and a PhD candidate at Wageningen University. His work focusses on techno-political innovations, blockchain, peer-to-peer technology and governance, global commons, radical municipalism, civic tech, the opensource movement and food waste innovation.

Dr. Alex Franklin is a Senior Research Fellow in Water and Resilient Communities, Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience at Coventry University. Her primary research interests are orientated around community resource use, shared practice, collaborative governance of green and blue space, ‘sustainable place-making’ and skills, knowledge and learning for sustainability.