Keywords:

Vernacular mapping, OpenStreetMap, informal settlements, smart city, cybernetics, Dhaka

By Liam Magee and Teresa Swist

Introduction

Theories of the smart city have often sought to integrate seemingly conflicting impulses between the logistical governance of populations and the creative activity of a liberated citizenry. Plato’s The Republic argued for rule by philosopher-kings who nonetheless would regulate a city of an enlightened demos. Straddling ideological lines, modern planning narratives understood city design and management as scientific programmes that would also not eradicate the glorious spontaneity of urban life. Mid-twentieth century socialist and communist experiments – of which the CyberSyn project of Allende’s Santiago and the New Unit of Settlement proposed for Soviet cities are two prominent examples – were as much guided by liberational aspirations as the neoliberal responses to modernist planning that sought an emergent “smartness” in market forces. Conversely, the neoliberal city has been no less preoccupied with techniques and technologies for the control, regulation and securitisation of financial and human capital.

The recent injection of digital technologies into urban development reinforces and reexamines these dynamics, albeit through new modes of authorisation. Sensors, video cameras, digital dashboards, automated transport ticketing systems and Big Data analytics are conspicuous examples of how cities can be smartened in distinct ways: made more convenient for commuters, more efficient for ratepayers, more governable by authorities and more attractive to investors. The smartphone materialises digital urbanism dramatically. The device par excellence of citizen science and individual autonomy, it facilitates everything from public transport notifications to “off-the-grid” communication networks. Yet it transmits data across networks maintained by large business, and through software offered by the current oligopoly of Silicon Valley corporations: Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook, which as of mid-2017 represent approximately 3% of the world’s GDP.[1] Such concentration appears to realise and refine the aspirations of earlier urban planners for command-and-control structures of governance.

This convergence of software supply reinforces the standardization and replication of sameness in the smart city (Easterling 2014; Verebes 2016). For Verebes (2016), this poses a “Dilemma of Similitude”, and requires a willful counter-tendency to preserve and accentuate the complex tones of urbanisation: “Questions remain as to what makes the specificities of cities, both in history and in a future which is definitively an urban future […] how, at the start of the twenty-first century, do we heighten the materialization of unique spaces and systems?” Others have pointed to the diversity that exists despite the desire for uniformity. Kitchin (2015) for example discusses “how different initiatives, led by a plethora of stakeholders, work together or compete to produce a certain kind of smart city”, one which is moreover inevitably marked by “the messy realities and politics of implementation and contestation” (p. 134). The smart city mutates difference as it self-replicates similitude.

Our study examines an example of this urban dynamic: the smartening of informal cities attempted by ICT4D (Information Communication Technology for Development) projects. To capture the tensions between a technologically-oriented standardisation and the diverse and dynamic irregularity of developing cities, we begin with an introduction of the cybernetically-informed concept of double bind. We further discuss this structure in the context of mid-twentieth century articulations of cybernetic cities that, with their utopic adventurism and despite different historical and ideological arrangements, project forward onto current efforts to peer-produce today’s smart informal city.

Advances in computing power and the availability of open source software promise to realise both the regulatory and the emancipatory aims of cybernetics. Situated at a conceptual intersection between smart cities, postcolonial computing and participatory design, GIS platforms such as OpenStreetMap create possibilities for what Gerlach (2012) has referred to as “vernacular mappings” – community-centred mapping efforts that seek to enact a political “multiplication of difference”. We describe an example of a vernacular mapping project, based in the Mirpur area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The project developed a Bangla-language smartphone app that extended OpenStreetMap to address service discovery and navigation through custom maps, databases, direction routing and social media feedback. Developed by an NGO (Non-Government Organisation) with the aim of promoting local community political agency and representation, the project’s tight feedback loop between software development, mapping, testing and use offers a practical case of the informal smart city at work. Equally, its ideological, logistical and technological overlays indicate a structure of double binding that is both specific to the contemporary smart city formulation, and echo important historical antecedents in the cybernetic city. We draw upon the maps themselves, focus group discussions with project community mappers, youth facilitators and software developers, and our own experiences and observations as project participants to discuss the tensions, complications and affordances of mapping informal settlements.

We conclude with considerations of whether the informal smart city necessarily entails the disorienting experience of a double bind, or whether instead the integration of technological standardization and infrastructural similitude simply amplifies the already complex conditions of precarious urban life. We discuss the contingent possibility of what we term “megaphonic publics”: grassroots networked collectives that agitate for their rights to the city through open source platforms and methods of peer production.

Background: Echoes of Cybernetic Cities

In Acts of Resistance, Scott (1990) distinguishes authorized from unauthorized gatherings. The former are controlled and sanctioned “parades”, while the latter are “crowds”, unpredictable, and somewhat threatening in their lack of formality. These urban gatherings are accompanied by their distinctive sound tracks: a trained band plays a particular march for the parade, while the crowd improvises an unrehearsed and unsyncopated performance. Yet often these tracks are distorted. Orchestrated percussion can be muffled by buildings, audiences and distance, while crowd cheers can develop their own rhythm. Similar contradictions attend the rapid rise of megacities themselves.

In South Asian megacities, where massive infrastructural standardisation develop alongside even more massive areas of informality, critique of the erasure of difference in the instantiation of the smart city overlaps with the ongoing attention to colonial and post-independence urban development (Datta 2015; Nair 2015; Mundoli, Unnikrishnan & Nagendra 2017; Varghese 2017). Concerns about neocolonial incursions of multinational technology companies and the fast-paced, non-deliberative productions of “entrepreneurial urbanism” (Datta 2015) contend with enthusiasm for the efficiency and democratic dividends technologies deliver to those living in informal and often impoverished settlements, where lack of access to essential services is both a logistical and political constraint on daily life (McQuillan 2014; Bunnell 2015). In relation to the many NGO-led initiatives to improve informal settlements with smartphones, sensors and networks, McQuillan (2014) further notes that “smart slums could still repeat the problematic cycle of first generation ICT4D if the technologies are dropped into communities without an effort to build the capacity of poorer citizens to use them”. As we discuss below, and as noted in scholarship of “postcolonial computing” (Irani et al. 2014) and participatory or reflexive ICT4D and HCI4D approaches (Ahmed, Mim & Jackson 2015; Wyche 2015), even such second generation capacity-building efforts are not without supplementary dilemmas of their own.

Definitions of “dilemmas” indicate two meanings: a situation requiring a strict choice between two mutually exclusive alternatives; or, more loosely, a “problem” or “predicament” (American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, n.d.). The first of these has been elaborated as a psychological state through the concept of the double bind, first introduced by Gregory Bateson and his colleagues in 1956. For Bateson, a double bind is a dilemma that is inescapable, “a situation in which no matter what a person does, he ‘can’t win’” (Bateson et al., 1956). Psychologically, it is a condition experienced by schizophrenics, formed by the repeated experience of primary negative injunctions along with secondary, more abstract and necessarily conflicting messages (Bateson et al., 1956). Bateson’s example of how this condition is produced involves a parent who repeatedly punishes or threatens to punish a child while simultaneously communicating non-verbally that such actions must not be interpreted as punishment, but rather as love. Eventually the child, as an actor without agency, cannot escape this continued and contradictory experience of punishment-that-is-not-a-punishment. The resulting confusion produces a breakdown in the recognition of logical categories, including those involving social communication, and a resulting flight into metaphor, hallucinations, and other conditions of schizophrenia. In a subsequent essay, Bateson (1972) clarifies the ontological status of the double bind: it is not a mental object lodged in the course of childhood trauma, but rather “an experiential component” that arises in the “tangle” or “breach” of rules of habit. This experience is ambivalent in terms of value, generating both the destructive pathology of schizophrenia and the culturally productive work done by humour, poetry and art.

The concept of double bind has been recently applied to sociological fields relevant to our own study. In his study of expatriate workers at Médecins Sans Frontières, Redfield (2012) analyses how contemporary NGO practice frequently involves various forms of a double bind, as “contradictory injunctions posed by a valued interlocutor, neither of which could be satisfied without failing the other”. In a more expansive account that encompasses contemporary processes of urbanization, Martin argues:

Urbanization is built on massive cracks. A widening gulf between wealth and poverty divides populations on multiple scales, both on the ground and in the social and cultural imagination. Differentials of race, class, and gender crisscross this divide, cutting new crevices and occasionally building bridges. These differentials, and the fissures and bridges they entail, are without exception enacted by material bodies, infrastructures, things. In general, the mediators and their political-economic entanglements observe the laws of the double bind. That is, they enable one set of possibilities while disabling another, equally plausible one, by delineating the horizons within which thought and action take place. In doing so, they reproduce the no-win scenarios of the double bind by appearing to reconcile mutually exclusive possibilities in a manner that is far more intractable than any ordinary contradiction (2016, p. 6).

While Martin’s argument does not here mention cybernetics explicitly, notions of feedback, the quintessential demarcation of the self-regulating and self-adjusting machine, feature heavily in his description of infrastructural mediators and the production of a “mediapolitics”. In an earlier essay, Martin recounts the cybernetic city envisioned by Norbert Wiener in a Life article published in 1950, “How U.S. Cities can Prepare for Atomic War”. Set amid advertisements for cigarette lighters and other articles about Nebraskan goose hunts, Wiener and his co-authors make the case for the “decentralization of our cities” and the installation of “lifebelts” – communications and transport networks that girdle urban centres. Analogous to Mumford’s “polynucleated city”, Weiner’s cybernetic urbanism foregrounds the defensive militaristic characteristics that include, in addition to decentralisation, “redundancy, information management, feedback” (Martin 1998). These were later to mark the network topology of the Internet and today have urban reverberations, in both boosterist and critical discourses of the smart city.

The respective languages of mid-twentieth century cybernetics and new millennial smart cities have been analysed in terms of their close intellectual, ideological and operational affinities (Gershenson, Santi & Ratti 2016) and, occasionally, differences (Goodspeed 2015). In some cases, cybernetic antecedents have directly motivated prescriptions for smart cities, as in the triple-helix model presented by Lleydesdorff and Deakin (2011) that draws explicitly from the systems theory adaptions of cybernetics by Talscott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann. Our own revisiting of earlier examples is motivated less by the specificity or refinement of models, and more by their historical recognition of “mutually exclusive possibilities” that smart cities, as megascale “mediators” in Martin’s sense, necessarily oscillate between.

Of the many mutations of the cybernetic city to emerge in the post-WWII period, the New Unit of Settlement proposed for Soviet cities in the late 1950s and the CyberSyn project of Allende’s Santiago in the early 1970s are distinctive in their marrying of futuristic urbanism to a language of collective emancipation and liberation that has re-emerged– often, but not uniformly – in the quite different individualised and consumerist discursive articulations of the smart city. The New Unit of Settlement was proposed by a group of Soviet architects led by Alexei Gutnov at the University of Moscow (Gutsov et al. 1968[1957]), at a time of heightened optimism about the prospects of socialism (Myers 2008). While it reinterprets prior prescriptions for urban planning from Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City movement, it also integrates the biomechanical language of cybernetics into its diagnosis of the ills of the city of “monopoly capitalism” (p. 21). Unplanned growth leads to the “megalopolis” (p. 23), a place that exhibits “functional disintegration” (p. 28), and produces “conditions of health and sanitation, traffic frustrations, a great waste of time, and the isolation of individuals in extremely confined spaces” (p. 8). By contrast, the communist city, strengthened by state-of-the-art scientific principles that include those of cybernetics but also “information theory, human engineering and the esthetics of technology” (p. 17), will set free the creative impulses of the urban citizen. In what seems a prescient premonition of contemporary techno-optimism, “automation opens up unlimited possibilities for machine specialization and for the consequent liberation of labor”. Acknowledging cybernetic feedback, planning also intervenes in the chaotic tendencies of unplanned growth: “the problem is not to limit growth as such, but to interrupt its linear continuity, to impose a systematic pattern and plan on its territorial expansion”.

Among other conditions, such detailed planning would require “a single comprehensive system of information storage and exchange” (Gutsov et al. 1968[1957]) that remained well beyond 1950s Soviet computational capacities. Planning in major Soviet cities eventually proceeded down lines that bore little resemblance to Gutnov’s ambitious urban designs. The CyberSyn project of Allende’s Santiago has received considerable recent critical attention, partly as it came at a time – only fifteen years after the Soviet city publication – when state-of-the-art computerization would make comprehensive and real-time state planning and monitoring conceptually if still not practically feasible (Espejo 2014). The confluence of a socialist government keen to develop a “people’s oriented economy” and with the arrival of Stafford Beer, a leading cybernetician and management consultant, led to a short-lived utopic social experiment that sought to direct incipient network and information processing technologies towards the creation of a utopic “liberty machine” (Espejo 2014) – an anticipatory form of what Medina has termed “sociotechnical engineering” (2011) and “algorithmic governance” (2015). While Pinochet’s right-wing coup in 1973 led to the abandonment of the project, its ambitions continue to echo in the urbanist discourses and have inspired other efforts to computational city management. Though directed toward the nation rather than the city, the project’s Operations Room in Santiago further anticipates control rooms that feature in famed smart city projects such as Rio’s Operations Center (Goodspeed 2015), and their virtualization through urban digital dashboards (Mattern 2015). Despite the fact that the smart city movement has been tied more directly to the rise of entrepreneurial urbanism, smart growth and new urbanism in the 1980s and 90s (Kitchin 2015), central tenets of the cybernetic city as imagined and planned in CyberSyn – interlinked networks, data flows translated into managerial information forms, scalar and granular organizational units that traverse governed centres and peripheries, and even the participation of citizens in monitoring and decision-making – remain integral to many articulations of the smart city today.

The double bind structure might be considered part of this legacy too. Its cybernetic underpinnings sought to avoid the deterministic logics that beguile technocratic states into delusory control, instead championing epistemological uncertainty and performativity (Pickering 2004). Yet even sympathetic accounts of CyberSyn still point to a radical overestimation of rational process, and an under-acknowledgement of the ideological tensions that tore at the dual pursuit of economic rationalization and political emancipation (Pickering 2004; Espejo 2014; Medina 2011; Medina 2015). The exteriorization of memory, cognition and information processing into mediator technologies of the screen, storage tape, telex machines and operations rooms constitute a point at which these new objects begin to make obsolete the old tools of bureaucratic statecraft. As Easterling (2014) has observed, they directly and essentially introduce “extrastate” actors in the scenes of governance: hardware and software vendors, IT standards committees and, more remotely, the firms that mine, manufacture and dispose of the material and logistic infrastructures essential to the continuous hum of the smart city.

Drawing upon Ashby’s (1965) ”Law of Requisite Variety’, Salingaros (2015) has argued it is the simplifying and dehumanizing effects of these industrial products and processes that triggers cognitive dissonance: “cultural norms demand a monotonous mechanical world, whereas human biology craves variety and ordered complexity” (p. 50). Within this particular conceptual unfolding, the double bind constitutes more than such dissonance experienced by an observer who stands on the periphery of the cybernetic or smart city. It is equally an affective dimension for those who, as observers, necessarily also participate and perform. Structurally, it develops not only from the abstractions codified as socialist, neoliberal or neocolonial ideology, but also through the agency of informatic infrastructures that function according to locally logically consistent processes – archetypically computational – and yet produce total situations full of impossible injunctions. The “liberty machine”, as imagined in Beer’s theorization of CyberSyn, applied the principle of “structural recursion” to management: differentiated in scale in factory, industry, networks and the wider political economy, but logically congruent across as well as within each of these systems.

The structure of the double bind suggests the simultaneous and repeated operationalisation of sociotechnical systems that are experienced as incongruent or dissonant. In today’s cities, these embed themselves as devices. Maps and software constitute examples of what Martin, in the passage quoted above, means by “mediators”, and which he elsewhere defines as “infrastructural, technical, and social systems that condition experience, delimit the field of action, and partition knowledge” (2016, p. 4). His account of infrastructural mediators includes, along with the conventional materials of architecture and urban planning, the new “hardware” of sensors, WiFi and Bluetooth networks, data centres, satellites and mobile phone: the very stuff that make up smart city infrastructure. The post-millennial participatory ICT4D project combines these mediators with the human subjectivity of urban communities, creating the ideal conditions for both everyday dilemmas and more profoundly disorienting experiences of the double bind to occur. In the next section, we explore one example of such a project, some of its impressions on local and foreign participants, and its contribution to a more diverse urban record.

Case Study: Mapping Services in Dhaka’s Informal Areas

In her sensory ethnography study in the slums of Govindpuri and neighbouring middle-class suburbs of New Delhi, Chandola (2012) argues noise acts as a vital sensory identifier of community and industry. Music amplified loudly by cheap equipment and “sonic performances of everyday activities” signals the liveliness of slum settlements, and annoys more affluent neighbours. The hum of factories once regulated daily routines of illegal camps; the closure of those factories and the resulting silence meant lost jobs and loneliness. According to one respondent, the silence was “deafening” and they felt “lost” (Chandola 2012). Without the noise manufactured by people and machines, the city is unnavigable.

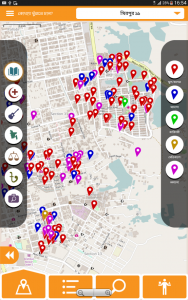

It is appropriate then that a community mapping project, developed with an explicit aim to boost political representation of residents of two informal settlements in Dhaka, was named Kolorob: ‘noise’ or ‘clamour’ in Bangla. Administered by Save the Children Bangladesh, the project ran from July 2015 until January 2017, and mapped local legal, health, education, government and other services into the OpenStreetMap database. As researchers we were involved in the project since its inception, invited by Save’s Australian office to advise on agile software development, interface design and evaluation methods. Our technical input included providing feedback on database structures, researching path finding approaches and data collection techniques for use with OpenStreetMap, adapting algorithms to respond to user input on irregular cartographic geometries, and suggesting ways to manage sprint cycles, versions, code refactoring and feature backlogs. We visited Dhaka twice, in February and November 2016, and communicated often with the technology team via email, Skype, and Slack, an instant message communications tool. During our visits, we also conducted focus group discussions with mappers, volunteers, users, other community members, and the software team. These discussions, involving between three and eight participants, covered detailed feedback on the Kolorob app, use of mobile phones and technology, and difficulties associated with locating and travelling to services in Dhaka. In our account, we include a number of screenshots taken from the app, to illustrate how the mapping results were ultimately rendered back to community users.

From the outset, the project planned to crowdsource a database of services, building upon the knowledge of local communities. Late in 2015, it engaged groups of volunteers to begin registering services in Baunia Badh and Paris Road areas of Mirpur. These two areas were selected based on Save staff’s familiarity with local communities and leaders, established in prior projects. Volunteers were recruited through existing NGO community networks, and through local advertisements. They were exclusively young adults, aged 18-20, and equally balanced in terms of gender. Most also lived in the target areas, and had therefore strong local knowledge of places and people. After an initial training session run by a small cohort of OpenStreetMap trainers, the volunteers worked with NGO staff to coordinate schedules and streets for mapping services systematically. Services were listed according to categories of health, legal, educational, NGO, government and commercial. Simultaneously, Save hired a small technical team to build the custom Android app for searching and browsing services, utilities for importing locations into the OpenStreetMap database, and a database system that would record supplementary information. Household surveys conducted in the early part of the project established a surprisingly high level of mobile phone ownership and use, especially among young members of the community. Our focus groups confirmed that most households possessed at least one Android smartphone, often shared between family members. While Internet access was slow and expensive, Wifi access points were beginning to be installed by NGO agencies, including Save itself.

Despite Dhaka being a large and rapidly developing city, and the target areas of Mirpur being reasonably well established, many of the services had never been mapped or recorded systematically before. With the exception of some schools, religious centres and NGO offices, Google Maps shows the areas as largely vacant, while previously OpenStreetMap had few if any buildings or streets marked. To provide some context, we describe the district of Mirpur, and the two mapped areas of Baunia Badh and Paris Road.

Figure 1 – Main interface of the Kolorob application, version 2.04 (released November 28, 2016).

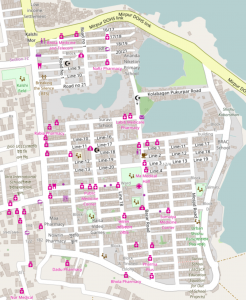

Mirpur was first established as a residential area in Dhaka’s north in the 1960s to accommodate “the lower and lower middle income groups and Muslim refugees from India” (Nilufar & Khan 2016, p. 81), and expanded rapidly after independence in 1971 in both area and population density. Despite being overseen by the Housing and Settlement Directorate, it lacks the “high space and service standards and physical designs” of nearby planned residential districts, Gulshan, Dhanmondi and Banani, that were developed to accommodate “high and high middle income families” and “expressed an aura of Western suburbia, modernity, and status” (Nilufar & Khan 2016, p. 81). The two mapped areas of Mirpur, Baunia Badh (Ward 11) and Paris Road (Ward 10), are distinctive relative to each other, and from their surrounding areas. Spatially, Baunia Badh is bordered by two main roads on its north, west and south sides, and small lakes to the east and north. As Figure 2 shows, it is internally well ordered, laid out according to a grid spatial arrangement that runs north-south and east-west, and is divided into approximate squares. It contrasts with the surround areas, which feature long, thin and often irregular rectangular blocks, a distinctiveness which stems from its origins as a UN Habitat-planned resettlement in the early 1990s. Despite the top-down appearance of order, at a street level it exhibits a mix of formal and informal characteristics, organised often with different land tenure arrangements. Street markets and shops on the periphery of the area are busy day and night, populated by bustling rickshaws, bird sales and mobile phone outlets. What appear topographically as streets on the interior are narrow lanes full of playing children, mothers standing on their doorsteps, and construction workers ferrying liquid concrete to construction sites. These sites are often vertical extensions, elevating what were originally one and two storey buildings to three or four, to generate further rents from what has become a constant stream of incoming migrants arriving from the countryside in search of work. Significantly, the lane ways that connect these buildings are far too narrow for emergency service vehicles or Google vans to penetrate; Street View stops at the periphery, and residents reported that Google Maps neither identifies many of the services and shops, nor the optimal routes of its interior.

Figure 2 – Baunia Badh area, Mirpur, Dhaka.

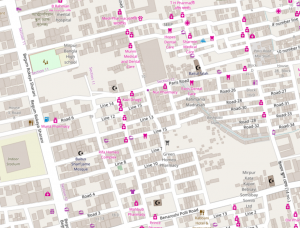

Paris Road is a less clearly demarcated zone. Large apartment buildings – some still in construction, and conspicuously marketed to Dhaka’s growing middle classes – straddle a streetscape of retail outlets that is just as busy as Baunia Badh. The wide street that gave the area its name has a growing array of fashion stores which point to the presence of the nearby garment industry. Yet in its interstices live a number of small, crowded and highly precarious slums, constantly under threat of seasonal flooding, waterlogging, earthquakes and eviction. Such threats readily materialise: in 2016 one of the slums was demolished to make way for more multi-storeyed development. Like other residents in Mirpur, people living in these slums contend with poor roads and open drains that overflow during times of heavy rain. Additionally, they struggle with problems of unemployment, unattended medical needs, high education costs, threats of sexual harassment and the experience of frequent conflicts between police and drug dealers.

Figure 3 – Paris Road area, Mirpur, Dhaka.

The direct recruitment of mappers and developers had not been done before by Save’s Bangladesh office. The local IT manager had prior experience with software development in an international firm, and together with the project manager, were keen to recruit internal staff rather than outsource development to a Bangladeshi or overseas company. Attempts to integrate external providers for parts of the development, such as the user interface design, proved difficult. Consequently, aside from occasional specialist technical advice, all product development was conducted by the Save team. This kept project costs low, and allowed for continued community feedback to shape development and adjust the mapping process. On the other hand, as discussed by the developer team themselves, the inexperience of a mainly young team led to occasional delays during software implementation.

Early work in 2015 developed the core materials of the project: survey forms for the community mapping activities; a review of existing open source directory service systems; and two briefs for Dhaka-based consultancies to develop, respectively, an experimental physical kiosk and a mock-up user experience and interface. Soon after, work commenced on an initial database design and app prototype, and project staff ran a series of community workshops, to introduce the project, encourage discussion and feedback, and encourage participation in the mapping process and use of the application. These proved invaluable in communicating the broad intended benefits of the project, and in generating interest and anticipation in the mobile phone application.

Simultaneously, mapping volunteers were recruited to begin mapping Baunia Badh and Paris Road services, walking street-to-street, using their phones to obtain GPS locations which were then recorded alongside the details of each service. These included basic information – the name, address, type and hours of operation of the service – as well as details particular to the service type. In the case of schools, for example, these details include their fees, year levels, facilities, average class size and number of bathrooms.

Initially this information was recorded on paper sheets, which meant a tedious and error-prone process of transcription into a database. In May 2016, the paper-based process was replaced by forms developed in OpenDataKit and OpenMapKit, digital tools designed to help community mappers record integrate locations into OpenStreetMap. Developed initially by Red Cross, OpenDataKit has since been widely employed by other humanitarian organisations to simplify and expedite crowd mapping. The efficiency and ease of the tool has also made it popular among research and government organisations (Esraz-Ul-Zannat & Haque, 2014). In response to further feedback, the technical team redesigned and simplified the structure and layout of forms several times. Each time required time-consuming modifications to the database and Kolorob app. By the end of the project, the time for entering a single service had decreased from thirty to ten minutes, and the use of geo-located tablets and highly structured forms improved the quality of records considerably.

The improved approach meant mappers could enter information about services directly through forms on their phones, and automatically register their GPS coordinates against each new record. This information was uploaded as a batch at the end of each day to a hosted service; after being validated at a later point, the same information was added automatically to the database. Service locations – though not the full set of data collected for each service – were also contributed back to the OpenStreetMap database. Figure 4 shows a section of the Baunia Badh district in OpenStreetMap as of November 2016, where specific health, education, religious and commercial services are clearly visible. Only a small number of these are marked on the corresponding Google Maps view in Figure 5, which also omits important lanes that could be used to provide electronic routing and navigation services. The substantial increase in detail illustrates the contributions of OpenStreetMap to participatory GIS initiatives, and in turn, the importance of those initiatives to the creation of global open data repositories. The improvement in quantity and quality of data led to unanticipated uses: for example, local leaders and community groups had begun to use the augmented maps to plan disaster management strategies.

Participants welcomed the opportunity to gain expertise and contribute to this mapping process, with one of the organisers stating they found learning how to map “quite interesting, definitely a new thing… to access the Internet through a map”, and another seeing further applications of participatory GIS in “DRR (Disaster Risk Reduction) for coastal people in Bangladesh”. Unsurprisingly for a project that employed largely young staff out of school and college, many also talked about the personal benefits of working for an international organization: developing public speaking skills, being part of a supportive team, and collaborating with communities on data collection, using OpenDataKit and setting up WiFi access points. Yet the excitement of developing such expertise combined with feelings of unease, as expressed by one participant: “For the last 2 years and they have learnt a lot about map use and technology using and they have many training – and they are now skilled […] If the platform created does not progress – will there be other projects to continue developing their skills on that project?”

If not quite the “impossible injunction” implied by the double bind, these comments suggest that at an experiential level, the project certainly produced ambivalence: enthusiasm, at the cost of future uncertainty. As we discuss below, this ambivalence repeats itself at scales of the ICT4D initiative and the would-be smart city.

Figure 4 – Close-up view of Baunia Badh, OpenStreetMap, November 2016.

Figure 5 – Close-up view of Baunia Badh, Google Maps, November 2016.

Discussion: Amplifying the Hidden Transcripts of Urban Clamour

The case study of Kolorob illustrates the ways in which participatory mapping of informal areas contributes to new authorisations of the informal smart city record. The process of mapping is often seen as an enactment for (to claim) or against (to contest) a piece of territory. Introduced by Peloso (1995), “counter-mapping” references mapping undertaken to undermine the dominant and hegemonic power structures that have historically mapped territories as means for asserting control over them. Over the two past decades, the term has resonated with indigenous, postcolonial and conservationist struggles to reassert claims or rights over disputed territory (Hodgson, D. L., & Schroeder 2002; Harris & Hazen 2005; Wainwright, J., & Bryan 2009). The open source qualities and accessibility of OpenStreetMap has seen it emerge as a kind of Wikipedia for cartography, a “massively distributed commons-based peer” produced platform for undertaking counter-mapping at scale and delivering “where expertise and justice are not in the exclusive service of dominants, but democratically available to all” (O’Neil 2011). However, as Gerlach (2012) notes, practices of OpenStreetMap mapping complicate the implied binary between dominant and non-dominant forces implied in the term “counter-mapping”. Instead, he argues its use is better described as “vernacular mapping”, a form of informatics layering that “look to always add to our abstractions of the world, to generate maps that attend to the everyday, to reorientate and disorientate bodies and things in the spaces of day-to-day life” (2012). Mapping, from this vernacular stance, is viewed as a more complex process – an enactment within a piece of territory. This process of producing individualised difference was suggested by a member of the developer team:

“Kolorob is making people able to make their own decisions which is better for them. The information I might get other people more easily I can see all information by myself and make my decision and I am not depending on another person and also increasing capacity for decision-making”.

While such affirmation may sometimes oppose existing power, the self-articulation that accompanies “seeing” and “decision-making” alongside the mapping process itself produces a vernacular mapping, an array of tonalities or perspectives. This articulation makes explicit – or at least less secretive – what Scott (1990) termed the “hidden transcripts” formed by the ongoing struggle between specific sites, practices, and dominant and subordinate actors. Scott further argued the ways in which these transcripts are often unheard, or restricted, relates to “the conditions under which they do or do not find public expression, and what relation they bear to the public transcript” (1990, p. 14). The process of vernacular mapping constitutes as a translating making public what had been previously kept hidden or repressed by the dominated urban classes.

Conversely, the very act of systematising this knowledge – abetted by international NGO staff, technologists, consultants and researchers, including ourselves – into digital form leads to other interpretations. Critics of ICT4D have argued the promotion of ICT, including open source platforms like OpenStreetMap, by international NGOs frequently betrays a “modernist” bias that equates the technological equipping of communities with social advancement or economic development. More often, this bias coerces communities into compliance with existing neoliberal and neocolonial interests, producing subjects ready to be co-opted into wider circuits of global labour, production and consumption (Andrade & Urquhart 2012).

As others have noted (e.g. Wyche 2015), such critiques are difficult to apply uniformly to the huge diversity of ICT4D projects, which run from websites developed by grassroots volunteer and activist community-based organisations through to multinational corporate platforms such as Facebook’s FreeBasics programme. Critiques of older ICT4D practice are being addressed by incorporating local and largely autonomous management structures, participatory design and indigenous approaches to software development, transition funding from overseas to local sources, and deliberative development (e.g. Irani et al. 2010; Hagen 2011; Donovan 2012). ICT4D projects also often run into more mundane difficulties. Against the enthusiastic rhetoric often espoused by agencies seeking donor funds to develop web and mobile applications, technical deliverables can be inappropriate for their intended audience, underwhelming in functionality, or discarded and unsupported once agency funding runs out. As noted by Poggiali (2016) in a community mapping study in a Nairobi informal settlement, these openings of social and technological exchanges produce complications, “as both potential vectors of sociopolitical recognition and as battlegrounds on which the urban poor’s claims to transparency are affirmed or ignored, heeded or disregarded” (Poggiali 2016).

Funded by Australian and US offices, and with an explicit mandate to self-fund by generating sustainable revenue, Kolorob is far from immune to criticisms of neoliberalism or neocolonialist smuggled in through technology platforms. It is situated within the same logic of the double bind Martin (2016) and others apply to the cybernetic or smart city: seeking to champion the creativity, knowledge and aptitudes of local communities, while subjugating them to the constraints of standardising technology platforms. Yet in important ways, it sought from the outset to work against “top-down” directives, whether from overseas advisors, Bangladesh government or internal management. The project was largely conceived, developed and managed by Save Bangladesh staff, with support from local partners and communities. One of the developers emphasized the local dimension of its technical outputs: “what Google is doing on an international level Kolorob is doing at a localised level”. Young facilitators, mappers and developers, many recruited from Baunia Badh and Paris Road areas, also had considerable input into the social and technical programming. Against financial and logistical constraints, local communities were consulted often about the application design and the accuracy and relevance of mapped sites. The project proceeded even without evidence of sustainable funding, and even at its completion the digital assets, including contributions to OpenStreetMap and the Kolorob app on Google PlayStore, remain freely accessible to use and further development.

The question of funding ICT4D projects links with those of evaluative judgment, of the conceptual sort we outline above, and also of more immediate practicality: do communities ultimately benefit from these new technologies inserted into their daily lives? In the case of Kolorob, the evidence is mixed, and susceptible to multiple interpretations. The difficulty in endorsing Kolorob as a case of counter-mapping or, conversely, criticizing it as yet another example of INGO meddling in local political economies is further complicated by the hybridised and intersectional face of intensive sociotechnical collaborations. In our conversations with local office staff, some felt the organization was unhelpfully competing against start-up companies that needed to establish brand awareness and business models around advertising services. Others thought the absence of a history of YellowPages-type directories in informal settlement areas instead signaled the need for large humanitarian agencies with funding to show government and corporate organisations what was possible. As one of the project’s field officers noted:

“we can work as a bridge so we can connect them with a better service or a service that they actually need and that is the advantage for Kolorob. That we are making this bridge so they can have access and so they need any type of information or anything they can just go for it – that is the main advantage that we are making that bridge for them”.

One of the explicit aims of the project had been to encourage social media ratings, reviews and dialogue about local services, and while this feature had only been partially implemented, our discussions with community members indicated the service directory helped gain access to government services and encouraged debate about how these services might be improved. Another of the field officers discussed how Kolorob was seen as valuable because people “have the information in their hands”, and therefore could utilise services more effectively. Whether or not this minimal citizenship might widen into other forms of participation, information access constitutes one of necessary conditions for greater representation for those living in Dhaka’s large informal settlements.

Despite it being a possible tool for critique, the Bangladeshi government appears to have welcomed Kolorob’s development, awarding it “Champion” in the “Inclusion and Empowerment” category of the Bangladesh National Mobile Application Awards in April 2017. An initiative of Digital Bangladesh,[2] a whole-of-government initiative designed to bring “public services to citizens’ doorsteps and increasingly within the palms of their hand”, this endorsement points to the accommodation of “unofficial” mapping within Bangladesh government discourse. Indeed, it is likely that nationalist concerns around exerting digital property rights to maps are very much subordinate to the current enthusiasm for promoting digital capacity building and economic development. In such contexts, fostering entrepreneurial software cultures and boosting mobile phone adoption appears to outweigh the state’s relinquishing of control over urban cartography. At any rate, if OpenStreetMap constitutes a form of vernacular mapping, one of its affordances as an open platform is that its data can always be reintegrated into proprietary company systems and or state governmental apparatuses.

Community mapping approaches, as Parker (2006) suggests, do not automatically bestow inclusion, transparency, and empowerment. Rather than a form of mapping that directly counters a hegemonic power, here the use of OpenStreetMap makes for a micropolitics that embroils actors in situations structured by contrasting and contradictory aims. These contradictions were not merely the product of bringing together NGOs, communities and companies, nor of conflicts generated by the confluence of local and Western expatriate and overseas-based staff. Indeed, from our own point of view as participant advisors and contributors, the working relationships across time zones and spatial divides were productive and complementary. In the Kolorob context, such injunctions rather multiplied in the form of orthogonal demands for economic sustainability, appropriate technology, institutional fit, international and inter-organisational collaboration, and localised political empowerment and participation.

Conclusion: Megaphonic Publics: Feeding Back and Forward

In today’s city, every smartphone is an Operations Room. Android devices can be purchased in Dhaka for less than $30USD. From Uber to localised digital dashboards, apps compress the noise of the city into curated graphical displays. Data pools and collects in centres that operate at scales scarcely imaginable to visionaries of Soviet cities and cybernetic economies. Electronic circuitry, wireless information waves and data registered on the silica of solid state drives agglomerates alongside human populations, concrete, asphalt, steel, glass and dust. This digital adumbration of the megacity allows us to think these telecommunication networks as a collective “megaphone”, complete with its amplifying effects. In contrast to information theory, here the signal is precisely its noise, a rising sound of static that constitutes an indeterminate political force through its very emergence (Hagen 2011; Chandola 2012). Far from eliding the smart city’s dilemmas and double binds, this urban clamour, and what we might further term “megaphonic publics”, instead amplifies the dissonance between official and unofficial records – and in doing so exposes channels as to how the right to the city could be authorized otherwise.

Ebullient smart city discourses almost will themselves to be written in response, and arguably, the ambivalent tenor of critical scholarship soon follows of necessity. Reaching back to the alternative socialist and cybernetic theorisations of the city need neither be contemptuous, nostalgic, nor reductive of the specificity of the contemporary urbanist moment. These earlier periods, couched within radically reduced technological conditions, instead anticipate a computational contingency that only appears naïve in the face of today’s deluge of information, the accelerationist tendencies of machine learning, and the emergence of cognitive capitalism. The imagined Soviet city desired informational capacity commensurate with the collective needs and desires of its urban population. In Beer’s acknowledgement of cybernetics as the science of the unknown, and in his premonitions of a post-computational world (Pickering 2004) lies a distinct awareness of the limits of the logic that governs digital processing. Communist and cybernetic cities are readily critiqued as examples of modernist overstepping. Equally, their imagining forecast a collective appeal therapeutic to the privatization of space, and an epistemological cautioning that the surfeit of smart city data – an entire population of public transport transactional data, for example, rather than samples with bias and margins of error – can otherwise blind us to.

The structure of double bind might arguably here be incorrectly generalized and ontologised from its identification within the specificity of a given ICT4D project or sociotechnical assemblage. Other projects, other problems and other arrangements might find ways to reconfigure those binds if, as Martin (2016) suggests, “knots can be cut and binds unwound, albeit with difficulty”. Alternatively, it might be feasible to consider this structure as, in the vernacular of software development, a “feature rather than a bug” of ICT4D and related humanitarian-technological work – a feature in the geographical sense, as something to be wrestled with in the landscape of the wider political economy. For the foreseeable future, types of platform and cognitive capitalism appear set to predominate. Within that horizon, neither willful ascent to the smart city’s commanding heights nor quietist descent into its labyrinths appear viable responses.

Dependent upon technological mediators, each case lies exposed to double binds that constrict realization of the complex utopia always implied in the qualified noun of “political economy”. The case of Kolorob, an ambitious and progressive engagement with urban informality, is no less subject to the “impossible injunctions” that attend humanitarian contributions to and adaptations of the smart city: to be inclusive, collaborative and participatory; to be agile and “fail fast” in software development; to deliver measurable social impact; to be cost-effective and develop sustainable business models; to align informality to the stricture of formal systems and logic; and to build technology appropriate to the diverse capacities that compose the informal settlements of megacities. Treated individually, these might constitute issues project managers and urban planners need to address. In aggregate, and considered from the long-term perspective of communities simultaneously hopeful and weary of waves of technological promise, they constitute the logic of the double bind we have attempted to analyse here.

Our focus here has not been to seek to resolve these contradictions, but to illustrate the ways the Kolorob project has posed them. At the level of implementation, it realized many of its direct aims, fusing together open platforms, social collaboration and software innovation to produce another instance of vernacular mapping, creating what Gerlach (2012) calls “a cartographic ethics that encourages the generation of maps that tell open-ended and inconclusive stories, of spaces constantly on the move and coming into being, an ethics that takes care of what might come next” (p. 167). It also contributed to the “massively distributed commons-based peer production project” (O’Neil 2011) of OpenStreetMap, and adds to the community empowerment arguments provided by Map Kibera (Hagen 2011) and other slum mapping projects. Traceable via the reverberations of mobile mediators and their wireless feedback, this process of recording and open-endedness continues one of the legacies of the cybernetic city: that alongside the accumulation of official and formal city archives, there are always unofficial and informal records.

With the project was in media res at the time of our fieldwork, how long these achievements endure is difficult to determine. We have dealt with the logic of the double bind at such length here precisely because the Kolorob case appears to exhibit its inescapable and paradoxical character so clearly: that the mechanisms that listen to the vernaculars of vulnerable, impoverished and previously silenced urban communities require those communities submit to new platforms of standardisation, and increasingly, of unwanted “listening in”, surveillance and control. Far from their intended aims, projects that seek to smarten the informal city may instead widen the “gulf between wealth and poverty” (Martin 2016), along with other divides. Conversely, systematisation meet specific resistance in informal urban areas: broken Internet connections and file-sharing work-arounds; irregular structures and pathways that defy cartographic representation; and social practices that utilise mobile phone information in unintended ways.

Future practical possibilities for smart informal cities can be sketched. Smartphone apps could be extended with statistics and machine learning to help migrating rural citizens evaluate job and housing prospects in different cities and districts. Community co-designed dashboards might provide real-time information and warnings about floods and slum evictions. “Mobility mash-ups” (Ching et al. 2012, p. 5) could improve public services and transport infrastructure. Informal technology training and mentoring could probe the uses of technology beyond the dominant platforms of information consumption, and prepare itinerant and casual workforces for other economic futures. Principles of platform cooperativism might be applied to the exploration of new models of legal land tenure. Electronic voting and feedback could be applied to issues of local development and governance. These and other possibilities open channels for an active listening to the collective and uncertain noise produced by the “requisite complexity” (Salingaros, 2015) of informal cities, and a further amplifying of the expertise of their citizens.

Further work needs to suggest and examine these and other participatory ICT4D possibilities, and as they unfold, pay particular attention to their long-term effects: do open source platforms and commons peer production authorise sustained political and economic rights to the city and its infrastructure? Or entrap populations within standardised systems that perpetuate existing inequity? The final double bind of the cybernetic and smart cities may be that their very dependence upon technologies that undergo change and disruption provoke reflexive, critical communities willing to interrogate and rework the structures of power that govern them. Under such conditions, as its citizens pick away at the double binds of urban formalisation, it might be possible to re-qualify the ‘smart city’ as one that incorporates spaces of clamour, participation and informality.

End notes

References

Ahmed, S. I., Mim, N. J., & Jackson, S. J. (2015). ‘Residual mobilities: infrastructural displacement and post-colonial computing in Bangladesh’. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, 437-446.

dilemma. (n.d.) American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. (2011). Retrieved October 30 2017 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/dilemma

Andrade, A. D. & Urquhart, C. (2012). ‘Unveiling the modernity bias: a critical examination of the politics of ICT4D’. Information Technology for Development, 18(4): 281-292. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2011.643204

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J. (1956). ‘Towards a Theory of Schizophrenia’. Behavioral Science, 1(4), 251–264.

Bateson, G. (1972). Double bind, 1969. Steps to an ecology of the mind: A revolutionary approach to man’s understanding of himself, 271-278. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Bunnell, T. (2015). ‘Smart city returns’. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1): 45-48.

Chandola, T. (2012). ‘Listening into others: Moralising the soundscapes in Delhi’. International Development Planning Review, 34(4): 391-408.

Ching, A., Zegras, P.C., Kennedy, S., and Muntasir, I. M. (2012). ‘A user-flocksourced bus experiment in Dhaka: New data collection techniques with smartphones’. Retrieved from http://www.digitalmatatus.com/pdf/Flocksource_JUT.pdf

Datta, A. (2015). ‘New urban utopias of postcolonial India: “Entrepreneurial urbanization” in Dholera smart city, Gujarat’. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1): 3-22.

Donovan, K. P. (2012). ‘Seeing like a slum: Towards open, deliberative development’. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, Winter/Spring 2012: 97-104. Retrieved from http://blurringborders.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/97-104-ST-Donovan-1.pdf

Easterling, K. (2014). Extrastatecraft: the power of infrastructure space. Verso Books.

Espejo, R. (2014). ‘Cybernetics of Governance: The Cybersyn Project 1971–1973’, in Social Systems and Design (pp. 71-90). Springer Japan.

Esraz-Ul-Zannat, Md. & Manirul Haque, Md. (2014). ‘Geospatial data collection using smartphone: ODK as an open source solution’. Bangladesh Journal of Geoinformatics, 1: 67-72.

Gerlach, J. (2012). ‘Vernacular Mapping, and the Ethics of What Comes Next’. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 45(3): 165-168.

Gershenson, C., Santi, P. & Ratti, C. (2016). Adaptive cities: A cybernetic perspective on urban systems. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.02000.pdf.

Goodspeed, R. (2015) ‘Smart cities: moving beyond urban cybernetics to tackle wicked problems’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1): 79–92.

Gutnov, A., Baburov, A., Djumenton, G. Kharitonova, S., Lezava, I. and Sadovskij, S. (1968 [1957]). The Ideal Communist City, Moscow University. Translated by Renee Neu Watkins, Preface by Giancarlo de Carlo.

Hagen, E. (2011). ‘Mapping change: Community information empowerment in Kibera (innovations case narrative: Map Kibera)’. innovations, 6(1): 69-94.

Harris, L. M., & Hazen, H. D. (2005). ‘Power of maps: (Counter) mapping for conservation’. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 4(1): 99-130.

Hodgson, D. L., & Schroeder, R. A. (2002) ‘Dilemmas of counter‐mapping community resources in Tanzania’. Development and change, 33(1): 79-100.

Irani, L., Vertesi, J., Dourish, P., Philip, K., & Grinter, R. E. (2010). ‘Postcolonial computing: a lens on design and development’. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1311-1320). ACM.

Kitchin, R. (2015). ‘Making sense of smart cities: addressing present shortcomings’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1): 131-136.

Leydesdorff, L., & Deakin, M. (2011). ‘The triple-helix model of smart cities: A neo-evolutionary perspective’. Journal of Urban Technology, 18(2): 53-63.

Martin, R. (1998). ‘The organizational complex: cybernetics, space, discourse’. Assemblage (37): 103-127.

Martin, R. (2016). The Urban Apparatus. University of Minnesota Press.

Mattern, S. (2015). ‘Mission control: A history of the urban dashboard’. Places Journal.

McQuillan, D. (2014). ‘Smart slums: utopian or dystopian vision of the future? The Guardian’ (7 October). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2014/oct/06/smart-slums-smart-city-kenya-mapping

Medina, E. (2011). Cybernetic revolutionaries: technology and politics in Allende’s Chile. MIT Press.

Medina, E. (2015). ‘Rethinking algorithmic regulation’. Kybernetes, 44(6/7): 1005-1019.

Mundoli, S., Unnikrishnan, H., & Nagendra, H. (2017). ‘The “Sustainable” in smart cities: ignoring the importance of urban ecosystems”. DECISION, 1-18.

Myers, J. C. (2008). ‘Traces of Utopia: Socialist Values and Soviet Urban Planning’. Cultural Logic, V: 2-23.

Nair, J. (2015). ‘Indian Urbanism and the Terrain of the Law’. Economic & Political Weekly, 50(36): 55.

Nilfur, F. & Khan, N. (2016). ‘Spatial Logic of Morphological Transformation: The Planned Areas of Dhaka City in an Unplanned Context’. In Rahman, M. (ed), Dhaka: An Urban Reader, Dhaka: University Press.

O’Neil, M. (2011). ‘The sociology of critique in Wikipedia’. Journal of Peer Production (RS 1.2).

Parker, B. (2006). Constructing Community Through Maps? Power and Praxis in Community Mapping. The Professional Geographer, 58(4) 2006, pages 470–484.

Peluso, N. L. (1995). ‘Whose woods are these? counter‐mapping forest territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia’. Antipode, 27(4): 383-406.

Pickering, A. (2004). ‘The science of the unknowable: Stafford Beer’s cybernetic informatics’. Kybernetes, 33(3/4): 499-521.

Poggiali, L. (2016). ‘Seeing (from) digital peripheries: Technology and transparency in Kenya’s Silicon Savannah’. Cultural Anthropology, 31(3): 387–411. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca31.3.07

Redfield, P. (2012). ‘The unbearable lightness of ex‐pats: double binds of humanitarian mobility’. Cultural Anthropology, 27(2): 358-382.

Salingaros, N. A. (2015). ‘The “law of requisite variety” and the built environment’. Retrieved from http://zeta.math.utsa.edu/~yxk833/TheLawofRequisiteVariety.pdf

Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Varghese P. (2017). ‘Smart-Cities for India: Why not Open-Source Villages?’. In: Chakrabarti A., Chakrabarti D. (eds) Research into Design for Communities, Volume 2. ICoRD 2017. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, vol 66. Springer, Singapore.

Verebes, T. (2016). ‘The interactive urban model: Histories and legacies related to prototyping the twenty-first century city’. Frontiers in Digital Humanities, 3(1): 1.

Wainwright, J., & Bryan, J. (2009). ‘Cartography, territory, property: postcolonial reflections on indigenous counter-mapping in Nicaragua and Belize’. cultural geographies, 16(2): 153-178.

Weiner, N., Deutch, K., & de Santillana, G. (1950). ‘How US cities can prepare for atomic war’. Life Magazine (18 December 1950): 78-79.

Wyche, S. (2015, May) ‘Exploring mobile phone and social media use in a Nairobi slum: a case for alternative approaches to design in ICTD’. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (p. 12). ACM.

About the authors

Liam Magee is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University. His research interests include the sociology of software, cities and urban culture, sustainable development, and innovations in digital methods and data analytics. Email: l.magee@westernsydney.edu.au.

Teresa Swist is Research Fellow at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University. Her research interests span the complexity and creativity of knowledge and cultural practices, philosophy of technology and education, ethical design, and the politics of data and participation. E-mail: t.swist@westernsydney.edu.au